This piece is 5,500 words or about 10 printed pages long.

See also the Beeching feature in Jacket 26.

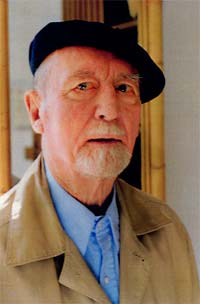

Jack Beeching in Menton, France, in his favourite blue shirt, not long before he died.

When Jack Beeching’s Poems 1940-2000 was published in early 2001 it went almost entirely unnoticed in the mainstream literary press and even in those magazines and journals which specialize in modern poetry. The nearest to public recognition seems to have been in a photograph of Doris Lessing in The Observer Magazine, 9 September, 2001, where his collection of poems was on top of a pile of books near her feet. Lessing was an old friend of Beeching’s from the 1950s but, apart from the handful of people who already had the volume, I don’t suppose there were many who spotted it in her possession.

The failure of the literary press to acknowledge the publication of this life’s work is all too characteristic of the more general neglect of Beeching’s writings. His poetry appeared in various little magazines and small press publications during the 1940s and 1950s and in 1959 Heinemann published his mildly satirical novel Let Me See Your Face. In 1970 a selection of his poems appeared in Penguin Modern Poets 16 together with poetry by Harry Guest and Matthew Mead. That was the highpoint of recognition and mainstream publication. His work has been virtually ignored during the past thirty years. There are no examples of his poetry in any of the standard anthologies of post-second world war English poetry and little, if any, mention in recent critical discussion. Even the encyclopedic Contemporary Poets has no entry for him, although he appears as a minor if significant character in Charles Hobday’s biography of Edgell Rickword.

The reason for this almost complete erasure from the record is difficult to explain and assess. By the end of the 1960s he was—as the first part of our study of his life and works noted—already leading a peripatetic, expatriate life and had therefore to some extent lost touch with the London literary and political circles he was associated with in the forties and fifties. But this cannot be the whole explanation.

It is the purpose of the second half of our article to explore and discuss the range and nature of his poetry and to justify a revisitation and revaluation of his achievement.

Beeching was born in 1922 — the same year as Philip Larkin and Donald Davie — and was therefore one of that generation of poets whose work came to maturity in the late 1940s and 1950s — although his work had very little in common in style or political orientation with the Movement poets dominant in that period. He published his first collection of poems in 1940 but very little of that work seems to have survived into his final Poems 1940-2000. It was not until his friendship and association with a number a Leftwing authors and magazines immediately after the war that his poetry began to take on its own distinctive style and direction. The influence of Auden was probably crucial and can be detected, for example, in “1848-1944”:

Everything was conceived then, when Europe became Europe,

When rebels became brothers, and there were no more speeches.

Soon, soon comes the consummation, the exiles returning

With arms in their hands at daybreak in the barges.

But the major influence on the development of his style and the consolidation of his politics was Edgell Rickword, a poet who also experienced periods of obscurity and neglect. Through Jack Lindsay, Randall Swingler and Rickword, he began to contribute to and assist in editing such magazines as Our Time and Arena and explore the poetic territory of an earlier generation of modernists. During this period he was earning a living by working for the communist publishers Lawrence and Wishart and as a journalist and advertising copywriter. A leftwing radical in politics, his stance was apparent enough in his poetry although he only rarely wrote in the overtly political-satirical style of Rickword’s famous “To the Wife of a Non-Interventionist Statesman”. Insofar as there are poems which show a particular political viewpoint, it is those which protest against the waste and violence of modern warfare—though in a manner and in imagery which recalls the first as much as the second world war:

As if borne down by too large a weight of thought

The bloody head lies prone. For flies a feast.

Over that man-shape, in small and tetchy lunges[,]

They swarm like scribbles, ghosts of mutineers,

Vindictive, ubiquitous, incessant, now come back

To haunt the field where flesh and blood submitted.

“Soldiers and Flies”—of which this is the last stanza—echoes the macabre and painful humour of Owen and, again, Rickword. “Commemoration 1932”, “Victory Ballad” and “Dead Airman Neighbour” tell a similar tale. There is sadness, anger and horror in these poems, a sense that the lives of a whole generation were shaped by these experiences; but there is also a curious detachment or displacement of emotion. “Our war heroes”, as he puts it in a tone which brings to mind his near contemporary, Keith Douglas, “were nameless, nameless, nameless”. In “Nameless” and in other poems of this time Beeching seems to be paying tribute to a certain kind of buttoned-up Englishness and the pleasures of a modest English landscape which is, as Seamus Heaney suggested in his essay “Englands of the Mind”, as much psychological as it is physical.

An early poem—possibly one of the few to survive from the first publication—shows how his perspective on the rural landscape of his childhood and youth was shadowed, haunted and distressed by the imagination of war. “Spring 1940”, whilst not entirely successful in its handling of verse line and phrasing, nonetheless is assured in its use of rhyme and metaphor:

Soon come young lambs, and the yellow

Daffodils, then the tractor plough

Will shave the frozen squares of fallow.

Soon we shall see hopscotch of bull and cow,

Then leggy calves, and the trees all pure bud-green.

As my heart beats, I think of French fields, how

Their rivers will thaw, their cuckoos sing, and then

Come screaming shells, and bright bayonets, and dead men.

The pastoral imagery of the poem is brutally discomposed by the imagery of war and suggests that the poet has absorbed lessons from Hardy, Edward Thomas and the first world war poets; and these influences are also evident in more subtle characteristics of the language: in the dissonant half-rhyme of “bud-green”/”dead men”, in the precise revived metaphor in “shave”, linking the earth turned by the ploughshare with the shavings from a joiner’s plane, and in the insertion of that “and” in the middle of the last line, which initially seems metrically awkward but is exactly to the point, to disturb the regular metre and create a jarring spondaic stress in the final syllables. The shock of exposure of the rural idyll to the new war is revealed in the beat. Rural idyll in fact quickly becomes elegy—at least in the poems Beeching chose to preserve—as in “A One-Time Village”:

This empty village crumbles. All have vanished.

Lost profiles agitate a fading fire,

And yet survive the marks their feet once made,

Hieroglyphs, beneath the grass and brier.

Or the longer reflective poem on land, inheritance and identity “The Resurrection of the Flesh”:

A tremor moves the ground beneath my feet:

Rejuvenating light, the sun returning,

Our flesh perpetual. There are no more ghosts.

They drift away, like smoke from bonfires burning.

“ ... no more ghosts” may be a deliberate echo of the title poem of a 1941 selection of the poetry of Robert Graves which is similarly preoccupied with landscape, heritage and the backdraft of war.

As we suggested in the first part of our study, the later years of wandering and self-imposed exile tended to create fixed images of England and the English and encouraged a rather dismissive and melancholic attitude towards late twentieth century British character and society. In “Nature”, for example, he writes:

Bluebell woods have changed to pastel doors.

Bud is a can of beer. Grey Saturdays

They sit inside, half-lit, and watch bright football,

Or odourless, instructive coloured Nature.

Triangles lost between motorways are Nature.

Birch and beech are twisted into chairs ...

And this view of things brings him in the poem “Life in a Rented Room” to a Larkinesque evocation of dereliction and reduced expectation and hope:

Crack, fissure,leak: nature will repossess

All that was burnt in kiln and sawn to plank.

Blot on the ceiling a chrysanthemum

Grown larger for All Saints, and that incessant

Creak from a shutter is a meaning hint:

You have this house on an uncertain lease.

The reverse side of this dyspeptic disillusionment with modern life is the continuing presence of positive images of the countryside — often though not exclusively the English countryside — to restore or reaffirm a sense of peace and fulfillment. This culminates in the elegiac “Nonno in his Garden”, a superb pastoral meditation on ripeness and decay. It is tempting to quote the whole poem, but these lines from the end will suffice to indicate its qualities of sensuous apprehension and meditative complexity:

The sprinkler whirls its arbitrary rain,

The figs turn ripe, and day and petals fall.

The garden, in the circle of the sun,

Reiterates its endless transformation.

But art creates the garden, every stem

Marked with a workman’s thumb, and this incessant

Manifestation of the feasible

Sets limits to the imperium of death.

An old man is his plants, the climbing boy,

For whom geranium is a nothing smell,

Is ripening fruit. His hand moves, picking them.

The setting in this case is Italian rather than English—Nonno Agostino was his wife Charlotte Mensforth’s uncle. But the poem taps into a rich English tradition of pastoral which in its rhetorical and metaphorical daring recalls the pastoral poems of Marvell and the odes of Keats. If the poem has any faults they are in a slight repetitiveness and unjustified extravagance of language; but, viewed as a whole, the pattern of seven, seven-line stanzas creates a coherent structure and brings with it a sense of both continuity and completeness. Like much of Beeching’s poetry, early and late, the language is formal and traditional although still anchored in a contemporary context: “the sprinkler”, “the tick of time” and the echoing of the boy’s idiom in “a nothing smell”.

Although the roots of Beeching’s poetic language are complex and various, like a great many young poets in the early 1940s the distinctive development of style, form and idiom in his poetry was strongly influenced by Yeats and Auden. Both can be heard in one of the poems in the “Aspects of Love” sequence: “Poem IX: For the fifth time I say”:

For the fifth time I say

My love in coded rhymes.

The words crumble away.

There once were other times

When I could hint and pun.

This time isn’t one.

The fifth time I assert

My bodily hunger,

Not hoping to subvert

Some possible stranger

But seeing the long body, in a bed

Of a girl simple as bread.

Four stuttering times

I tried in clever verse

To marry my love to rhymes,

But made this hunger worse,

Seeing your face so clear

I felt you had come here.

This is the fifth. I don’t care

If the verses rhyme or scan.

I just write down my despair

That love for a woman

Which I thought would never come

Has left me hungry and dumb.

Hungry for the sight

Of the way she turns her head.

Trying to live in the light

Of ordinary words she said.

Longing like a child for her touch.

Loving her body so much.

The idiomatic lyricism recalls Auden—in “Lay your sleeping head, my love”, for example — and “I just write down my despair” seems a specific allusion to “I write it down in a verse” in “Easter 1916”. But whatever the echoes this is a beautifully measured love poem and the final astonishing lines—with their transformation of “ordinary words” into luminescent feeling and affective power — are Beeching at his best. In early twentieth century love poetry only DH Lawrence and Paul Eluard create verses which are as simple, sensuous and direct.

Auden and other 1930s poets clearly provided Beeching with a poetic idiom and confirmation of his political standpoint. In a short poem, “Book Review”, for example, he pays tribute the young communist poets John Cornford and Hugh Sykes Davies and also slams orthodox literary critics and scholars. But it was Edgell Rickword who plunged him most thoroughly and effectively into the modern. “Aspects of Love” (1950) is dedicated to Rickword and he was undoubtedly a direct, seminal and major influence on Beeching in the 1940s and continued to be an example, mentor and friend throughout his life. The span of the association is indicated by the fact that Beeching reviewed Rickword’s Collected Poems for the magazine Our Time in 1948 and contributed to the PN Review special supplement on Rickword in 1979.

Rickword is also a poet who has periodically suffered neglect and misunderstanding. As a poet, he was one of the foremost exponents of modernism in English and, as a critic, made it his mission to interpret modernism to the English-speaking public and to evaluate its impact and potential within the traditions of English verse. Rickword’s is not the modernism of the Imagists, Poundian vers libre and the fragmentary poetic structures of Eliot’s The Waste Land. Such experimentation does not seem to have appealed to him, and the only exercise in the style in his own work is the parody of its mannerisms and forms in “Twittingpan: The Encounter”, an acid and unforgiving satire on 1920s literary and intellectual culture:

‘Consider Bond Street,’ as we reached it, cried

falsetto Twittingpan our period’s pride,

‘Does it not realize in microcosm

the whole ideal Time nurses in its bosom?

Luxury, cleanliness and objets d’art,

the modern Trinity for us all who are

freed from the burden of the sense of sin.’

Rickword’s modernism grows out of Baudelaire, Rimbaud and, from the twentieth century, Valery and TS Eliot—though it is the Eliot of the essays rather than — or as much as — the poetry. Commenting on The Waste Land in a review, Rickword noted that “he [Eliot] is sometimes walking very near the limits of coherency” and, for all his sympathy for the modernist experiment, Rickword remained faithful to an idea of coherence and intelligibility. His reasons for this practice and belief are as much political as poetic and may explain why his work culminated in political satire and commitment rather than religious introspection. During the 1920s Rickword produced a small but distinguished body of work which included anti-war poems, ironic “observations” of bourgeois mores and society in the style of Eliot’s Prufrock volume (though almost certainly influenced by Baudelaire, Rimbaud and Corbiere) and a group of meditative poems (“To the Sun and Another Dancer”, “In Sight of Chaos”, “Prelude, Dream and Divagation”) which opened up new possibilities for the metaphorical exploration of contemporary life and feeling.

Beeching clearly found Rickword’s political commitment congenial in that it was at once anti-establishment and positive about the nature of a just society. But the influence and affinity extended beyond political agenda and stance. Rickword’s modernism shows itself in a certain kind of “Englishness”, at once ironic and assured in tone (Empson is another exemplar of the mode), and in the development of a style which assimilated some of the lessons of late nineteenth century and early twentieth century Anglo-American and French poetry in terms of subject-matter, persona and perspective and the use of image and symbol whilst retaining formal control and “coherence” through adherence to traditional metre, stanza and syntax. As we have already noted, in the poem-sequence “Aspects of Love” we can observe the poet experimenting in prosody, verse forms and imagery, and still searching for or in the process of defining and appropriating his themes. Beeching picks up on the metaphorical and elevated tone in Rickword’s mature style but by the early 1950s was already weaving it into a complex rhetoric which was largely his own. The conclusion of the poem “Dead Reckoning Day”, for example, illustrates the style:

The common mother we are bound to love

Lifts up her scarlet hands in accusation.

Only the dead can bear this blame no longer.

O mother-murderer, source of every river,

Put rock on rock to build your sons a tower,

Sow wheat like crosses on the holy acre

And take in yours our mercenary hands.

The poem is by no means entirely successful in all its details but as a whole it is an impassioned exploration and denunciation of betrayal, deprivation and social injustice. If there is an echo of Hart Crane’s “Voyages” in the last line, it is perhaps no accident. Rickword was Beeching’s bridge to Baudelaire and Rimbaud, on the one hand, and to the modernism of Crane (and possibly Allen Tate and Wallace Stevens) on the other. “Outside the Cinema” and “On Trying to Breathe in Rome” show the direction his poetry was taking in the 1950s. “Faces in the Parlour” indicates the strengths and possible weaknesses of the style:

This is a shrine where faces of the Dead

Stare from a still piano. No one looks

At wallpaper or curtains. No one reads

The ribboned letters and the gilded books.

Prizes were dusted and the curtains drawn

Only at marriages and christenings.

Now we speak Christian names and sip our wine

In black November as her death tolls rings.

This hard and buttoned sofa was for courtship

Each wineglass christened once the bride’s new name.

The mirror saw her snowy veil turn mourning

For two dead men an enemy overcame.

The victor now, dropped in her family grave[,]

Sleeps in her oblong parlour like a nun,

Until compelled by earth’s undying worm

To mingle flesh with father and with son.

As a picture of middle class life after the second world war, the language of the poem is appropriately restrained and the epithets are precisely descriptive whilst at the same time carrying symbolic or associative meanings. The “still” piano, for example, describes the unplayed instrument but also suggests sterility and unfulfilled potentialities and desires. Similarly, “gilded books” creates the image of gilt-lettered book-spines whilst also calling up an idea of middle-class gentility, pretension and keeping-up-appearances. The “hard and buttoned sofa” carries similar associations and, further, suggests an un-giving and unforgiving ethos and mentality. The household described in the poem is “possessed by death” not only because it is about a funeral but also because it evokes a moribund way of life which has been destroyed, at least in part, by death in war. The subject invites — or demands even—sympathy, condolence and sorrow, which is there in some measure. But it is undercut both by an ironic tone: “Now we speak Christian names and sip our wine” and the gruesome imagery of the last stanza where the reference to the “father” and the “son” killed in the war is a direct parody of the Father and Son of religious faith. Faith offers scant joy or consolation in these circumstances. The widow (“victor”) and grieving mother is “dropped in the family grave” and “compelled ... /To mingle flesh” in a manner which unceremoniously emphasizes an “earthly” rather than transcendent end.

The poem’s weakness perhaps is that, although cleverly wrought and full of significant detail, it is a little pat in its resolution, the ending already predicated in its opening line. In a poem which is after all as much macabre satire as plaintive lament, this is no great failing; but it does signal a tendency in Beeching to have too much of a design on the reader’s feelings and response. In the best of these poems, however, Beeching achieves an intricate structure of language which articulates — with gravity and wit — complexities of thought, feeling and experience.

“Panopticon, Or Penitentiary Love” is a good case in point. The poem, to borrow Rickword’s phrase, walks close to the limits of elaboration; but the extended analogy or conceit of the panopticon as a way of exploring the idea of love as a form of imprisonment which compels (or permits) the lovers to examine all sides of the self and the other justifies itself in creating a subtle and well-wrought whole. The poem deserves to be quoted in its totality, but these lines from the middle section will illustrate its intricacies of image and tone:

Love interpenetrates. The cleaving pair,

Graphic in the passion of their dance,

Alternate, as if hermaphrodite.

Mouth upon mouth, I might as well be you,

Both beatrice, both poet, act of love

A fourfold minuet. All singletons,

Smug and domestic, flinch from this insight.

After the hazard of the please and yes,

Catherine wheel of carnal unison,

Lovers are lured towards a last desire:

To enter and possess each other’s dream:

Grasp for a last oblivion. All who change

Identity crave innocence again.

Two into one are never what they seem.

The language of the poem suggests a direct line back to Donne in its allusiveness and intellectual complication; and the poem must contain one of the first — or at any rate one of the few — uses of the word “singleton” in poetry, a pun on the term in card-playing which also means the separate or unattached person. The play with language also stretches to a metrical play on “insight” where the beat of the line virtually enforces a reverse of the usual stress (from the first to the second syllable) and thereby takes us to the root of the word as a “looking within”. The poem concludes:

That crowded street outside is carnival.

Eyes interlace, gestures of recognition

Detonate. Work done for love transforms

The commonplace world to one vast simile

Where wave and cliff, at last promiscuous,

Lift up their foaming heads, as they foreswear

The basilisk face of dread they used to wear.

Past years are clouds of dust, blown in the wind,

Endlessly pouring through time’s tapering glass,

Our firmament a shovelful of sand.

Out on the street, fantastic because real,

Is life made equable by human hand,

Where an observing eye, half-closed, discerns

Possible dreams, that have the power to heal.

The poem as a whole is a curious cleaving of modernity and tradition, with allusions to Dante and Donne interinanimating the distinctively contemporary setting, tone and attitude. It would sustain a detailed analysis and interpretation. Any self-respecting anthology of twentieth century love poetry ought to include it.

“Panopticon, Or Penitentiary Love” is one of a series of increasingly ambitious poems and poem-sequences which Beeching was writing in the 1950s and 1960s and which were published in Truth is a Naked Lady (1957)—possibly the worst title for a pamphlet of poetry in the 1950s, and one which was almost entirely inappropriate for its contents—and in Penguin Modern Poets 16 (1970). Many of these poems were revised, extended or simply re-titled for publication in Poems: 1940-2000. They explore themes of self, city and exile in a language which has become in style and manner recognizably Beeching’s own. There is always the danger in Beeching—as we have already noted—of a kind of rhetorical afflatus and an over-assertiveness of manner. These are failings shared with Crane and Dylan Thomas, for example, or with the New Apocalypse poets of the 1940s. Unlike these poets however his poems rarely suffer from a willful or merely idiosyncratic obscurity. It seems rather to derive from a situation in which he was more used to speaking to himself than engaging in conversation with others; a man and poet more used to giving forth than listening. This may be a little unfair — and is almost certainly one of the consequences of his wanderings and self-imposed exile — but it is nonetheless true that there are very few poems (though the exceptions are remarkable) in which he writes sympathetically of the experience of others. Of the self, however, he writes with increasing acuity. In a poem in a sequence called “Exile in Time”, for example, he writes on a theme which also preoccupied Thom Gunn in his existentialist explorations of touch and identity:

Living within the frontiers of my skin,

Feeling my way with diplomatic fingers,

Defiant eyes observe this foreign land,

Seeking in every counterpart a mirror,

The long-lost twin, one who will understand.

Exile is privacy.

The poem explicitly associates the problematics of selfhood with exile, outsiderness and alienation and ends with a delicate and touching expression of desire for intercourse, social and sexual:

But hand meets hand in darkness, candlelight,

With eyes nearby as sanctuary, invoking

The little death that marks the private midnight.

Jack Beeching in Charlotte’s studio, Menton, France, c. 1990.

Such moments of vulnerability are rare in Beeching (cf. “Poem IX: For the Fifth Time” quoted earlier) and even here the vulnerability is mediated by the ironic use of the trope of “the little death”.

The expatriate poet, the poet as exile and outsider, becomes a central concern in Beeching’s poetry from the late 1950s and reflects of course his wanderings through Europe, the Middle East, Latin America and—for a brief sojourn—the United States. The poetry tracks Beeching’s progress through a variety of involvements, contexts and settings and focuses on the political and cultural as much as the physical landscape of the place. “A Low Bar in Guat City” gives a comic if somewhat edgy representation of the experience of the lone traveler in an unfamiliar, foreign police-state environment:

Here on this stool, awaiting a tap on the shoulder

.....

Plain-clothes cop. He holds me by the coat.

Thanks. I never smoke.

Sat here drinking, all the afternoon.

Young man who looks like this? Now let me see.

.....

Was here? You saw him go?

I may have done.

Down some blind alley, on a horse called Fury.

“Writing on the Wall” and “The Dictator Dead” give a more graphic picture of the uncertainties and oppressiveness of a dictatorial regime. These lines from the latter poem, for example:

At the first light, a stranger with a broom

Sweeps up the flux, yesterday’s newspapers,

Our splintered bannerpoles, the smudge of blood,

Inhuman confrontation, crippled limb.

Wreckers broke down the sunflower brow of hope.

Survival is a workman with a broom

Scuffling words like torn-up paper napkins.

Eyes avoid eyes. We watch our step this morning.

Political experience, personalities, ideas and iconographies are constantly represented in the poetry, particularly in the 1960s and 1970s. But so is the continuing, brooding sense of being an outsider, of dissociation from permanent engagement and loving relationship. This theme—the dissociated and divided self—is pursued, poignantly, in “Opposites Reconciled” and the poem-sequence “Here is Nowhere”; or, defiantly, in “The Freehold of Himself” and, mysteriously and indirectly, in “Flamingoes on Formentera”. “The Door”, written in terza rima and reiterating an image of imprisoned being which is a recurrent motif in Beeching’s work, is another clearly articulated example of the idea:

The door is what divides, a kind of spell

For keeping men apart, each with his thoughts.

A man behind a door is in a cell.

.....

Waiting outside is one who would break in?

Then here’s another, aching to break out,

Rub shoulders, chat, with an accomplice grin,

Answering from a solitary face,

Street shoes, dark sweater, midnight on the town

In bars where misfits find a meeting place.

If the poetry of exile articulates one form of alienation, the poetry of the city articulates another. Indeed the two forms of alienation are often conjoined in poems which Beeching was writing in the 1960s and 1970s. Insofar as Beeching was a Rickwordian modernist he found the exterior and interior landscapes of the city appropriate territories for his art. As the pencil drawing on the flyleaf of his collected poems shows — a dapper man, with a trim beard and a broad-brimmed hat worn at a slightly rakish angle—Beeching was a dandy. Or rather, he found it convenient to use the trope of the dandy or Baudelairian flâneur as a way of exploring his experience, urban and urbane. In a short, self-ironical poem he presents himself as “A dandy dressed up in old clothes” and a number of longer poems and poem-sequences—“Myth of Myself”, “Here is Nowhere” and “Exile in Time”—the modernist engagement with urban perspectives is fully explored.

The themes and preoccupations of Beeching’s writings—personal, political, historical and philosophic — are diverse and variously treated. It may be however that his deepest mode is the elegiac, a mode and mood beautifully caught in “The Music As It Fades” which ends:

Time has turned over, year comes to an end

With customary songs and escapades,

Make-believe salutations, glycerine tears.

You hardly hear the music as it fades.

The delicate cadence of the last line perfectly exemplifies Beeching’s intuitive skill as a prosodist, a skill which is further and diversely exemplified in the many tributes to those killed in two world wars in his early work and in the several epitaphs to family members which includes the caustic “In Memoriam HB”:

With fur in mouth and ears,

And stink inside his head

And only his heart sweet

My uncle, who is dead,

Spent forty poisoned years

Sorting furs, for bread.

The elegiac mode is also evident in the gentler memories of his grandfather and in the poems to dead friends such as “Night Companions”, an ironic, self-mocking poem which brings to mind the bitter-sweet reflectiveness of some of Hardy’s melancholic, midnight meditations:

What do they want of me, coming here at night

To catch my eye, or touch me on the arm?

The elegiac is often represented in a lament for what Rickword called the “depopulation of rural districts” which relates to traditions of pastoral poetry mentioned earlier.

Towards the end of his life Beeching transformed the elegiac theme into an elegy of the self. Illness and a growing sense of his mortality, perhaps, inspired him to write a series of poems which take stock of his life and achievement and create images of himself, in slow decline and dissolution, translated from elegant flâneur to aging solitary and survivor. In “Fingernails”, for example, he writes:

On Sunday morning, trim moustache and nail[,]

Adjust a mask of years across your face,

Shave and perform the usual ablution,

Leaving the worms to give the final polish

To your invisible armature of bones

In the long afterwards of dissolution.

This complex and self-consciously elegiac direction culminates in “Intimations” which is a group of poems written in the last two decades of his life and which is as much occupied with intimations of mortality as of immortality. Taken together, they fashion a personal valediction. In “Curriculum Vitae”—the last poem in the group and the final poem in Poems 1940–2000—Beeching has written an ironic, self-questioning and self-knowing personal epitaph, an apologia which at once examines, orders and justifies the life. The poem deserves to be quoted as a whole but the last stanza must suffice:

Captive in this citadel, last survivor,

Soaping my ribcage, on the tongue I tasted

Brine. This then is where one’s old and secret self

Learns to drown: river a sign of grace,

Rising sap or flood of mother’s milk:

Past life alive, and now becoming ever.

The poem is an extraordinary achievement, the product of a lifetime dedicated to language, meaning and self-understanding. The rhythms and imagery and the complex elaboration of theme recall Donne, Keats, and Hart Crane at his best. Yet the poem as a whole is wrought into a style which is recognisably Beeching’s own. The rhyming of “survivor” with “ever”, for example, and the way he rhymes first and last lines in each stanza throughout the poem, is a characteristic touch, indicating seriousness without solemnity and the intensification of feeling through irony. Here, as only rarely in the lyrical-meditative poem, the self, the personal, is both revealed by and submerged within the theme, the individual talent translated into tradition.

Beeching deserves greater recognition. His work is uneven in terms of structure and language but it contains a sufficient number of fully achieved poems to make it substantial and significant. He made an important contribution to English modernism after the false starts of the Pylon and New Apocalypse poets in the 1930s and 1940s and he provides part of the missing link between the generation of Rickword and the postmodern poets in English in the last decades of the twentieth century. But the poems—as we hope to have demonstrated — have pleasures and insights of their own. The publication of his Poems 1940–2000 in 2001 was certainly welcome and made possible, for a few, a reassessment of his work. But there is surely a strong case for a selection of his poems by a major English poetry publisher in order to make his work more readily available to a larger readership. The re-discovery and revaluation of his writings would not perhaps totally alter our perceptions of developments in English poetry in the later half of the twentieth century; but it would add an important chapter to its history and to the pleasures of reading.

Jack Beeching Poems 1940–2000 (Collection Myrtus) 2001 (Distributed: c/o 67 Sunnyside Road Chesham Bucks HP5 2AP)

———, Truth is a Naked Lady (Myriad Press) 1957

———, Penguin Modern Poets 16: Jack Beeching Harry Guest Matthew Mead (Penguin) 1970

———, Let Me See Your Face (Heinemann) 1959

Edgell Rickword Collected Poems (Carcanet).