BOOK REVIEW

Colin Browne reviews

Shadowtime

Composer: Brian Ferneyhough; Librettist: Charles Bernstein; North American premiere:

Lincoln Center Festival 2005, July 21 and 22, 2005

Shadowtime, by Charles Bernstein

134 pp. Green Integer Books US$11.95 1-933382-00-7 paper

This review is 5957 words

or about 15 printed pages long

Benjamin’s Angels, or

Why We Sing the Lamentations

1.

In a fascinating 1995 interview with Florian Vetsch in Tangier, Paul Bowles refers to Gertrude Stein and Virgil Thompson’s

Four Saints in Three Acts as a ‘kind of opera’ — saying so is like raising an eyebrow — although there’s a typo in my edition and Bowles appears to say “king of opera”. (Bowles, 82.) I was reminded of this slip in July when visiting the Metropolitan Museum of Art on the afternoon of

Shadowtime’s New York premiere. The familiar paintings and sculptures in the permanent collection of modernist art have become, to my mind, a collective conscience concerning the nature of modernity. They stand as harrowing witnesses to the charnel house of the first half of the twentieth century. The psychic disturbances, the repression and the almost inconceivable suffering these works represent have become amplified over time. It may just be me, but as I walk through the galleries I hear whispers of ‘J’accuse.’ And so, on that sunny July afternoon, absorbed by such thoughts, I was not prepared to confront the gaze of Picasso’s regal portrait of Gertrude Stein.

Left, Brian Ferneyhough; with Charles Bernstein, July 2005

Gertrude Stein (1874-1946) was a kind of monarch, and her lifelong performance as Gertrude Stein has attracted its share of dramatists, screenwriters and librettists. Compared to philosopher and cultural critic Walter Benjamin (1892-1940), she has always seemed larger than life. It’s difficult to imagine Benjamin’s brief span providing the material for any kind of opera, although his tragic death has gripped the imaginations of scholars throughout the world.

The story is by now well known. Having waited until the last minute to leave occupied France, Benjamin and three companions fled across the border into Spain one night in September 1940. (Benjamin was on his way to the United States via Lisbon.) Arriving in the little town of Portbou, the refugees discovered that the authorities had declared their Spanish transit visas invalid. They were instructed to spend the night under surveillance and the next morning the Spanish police would escort them back across the border into France. For Benjamin this meant incarceration and certain death. In a small hotel owned by a man who kept himself on friendly terms with the Gestapo and the local police, Walter Benjamin appears to have swallowed an overdose of morphine pills. Had he waited for a day or two his visa very likely would have been approved.

Walter Benjamin was barely forty-eight years old when he died, and as an intellectual force his loss is incalculable. We can be grateful for his unfettered curiosity, his generosity of spirit and his ability to sniff out and expose the unholy brew of political ambition, self-delusion and mystical nationalism. Today he’s accepted as one of the significant European thinkers of the twentieth century, and with new translations and collections of his work appearing in English, more readers than ever can appreciate the passionate contradictions at the heart of his thinking and the intellectual honesty that set him apart from the hard-line ideologues of his time.

Benjamin was a scholar of consciousness, a Marxist who believed in God, a theologically-minded interpreter of the profane whose brilliant essays on new technologies and photographic representation seem as relevant today as when they were composed. He was an activist and dissenter with an abiding interest in Judaism and the Hebrew language, yet he was suspicious of what he called ‘the agricultural orientation, the racial ideology, and Buber’s “blood and experience” arguments’ associated with Zionism. (Scholem, 37.) He experimented with hashish, enchanted by its possibilities for enlightenment; he studied graphology, public markets, drama and poetry. As a young man, Benjamin had decided that the best form of government was ‘theocratic anarchism.’ His later work often puzzled his contemporaries who looked to him for solidarity. The famous essay on mechanical reproduction confused his colleague Hans Sahl who found it ‘all very mystical despite his anti-mystical attitudes.’ (Brodersen, 239) In a time of fierce ideological commitment and flag-waving, Benjamin was never an ideologue. His technique as a writer paralleled Eisenstein’s as a filmmaker; both can be said to have subscribed, in spirit, to Blake’s insistence that ‘Without Contraries is no progression.’ Benjamin’s earliest articles were signed with the

nom de plume ‘Ardour’.

As a young scholar, according to his friend Gershom Scholem (1897-1982), Benjamin ‘saw no need to discover ‘the meaning of the world’: it was already present in myth. Myth was everything; all else, including mathematics and philosophy, was only an obscuration, a glimmer that had arisen within it.’ (Scholem, 39-40) Later in life, in his materialist phase, he lost interest in myth and ritual only to regain an interest in their role in his final years. Scholem tells us that Benjamin always had ‘a pronounced sense of the emblematical,’ which is perhaps why he appeals to us today, absorbed as we are in the hermeneutics of signs. He was prophetic in the Blakean sense, which is to say, as Robin Blaser would remind us, that he was capable of seeing into his own time.

Benjamin took a special interest in the philosophy of history and the nature of memory, and was particularly moved by and attracted to Proust’s notion of’

‘mémoire involuntaire.’ Typically, when we refer to memory, it’s to ‘voluntary memory’, or conscious memory, which is retrievable (if we’re lucky) and to some degree knowable. Benjamin wanted to draw attention to the vast repository of ‘involuntary memory’ hidden in the unconscious, rarely accessible and often traumatic in nature. His 1939 essay on Baudelaire included Freud’s observation from

Beyond the Pleasure Principle that ‘...memory fragments are “often most powerful and enduring when the incident which left them behind was one that never entered consciousness.”‘ (Benjamin, 160.)

Consciousness, according to Freud, had a responsibility to protect our psychic systems from disturbing stimuli that might be associated with traumatic, often overwhelming incidents that found their way into the ‘involuntary memory.’ At the same time, Benjamin, and others, believed that culture had a responsibility to reclaim these incidents, to acknowledge and understand them. The same was true for individuals. He came to distinguish between what he called ‘lived experience’ and ‘true experience.’ ‘Lived experience’ was related to voluntary memory and referred to the events of a life repressed by time, consciousness and human institutions. ‘True experience’ had to do with being alive to all one’s faculties and memories, a condition we move toward when we embrace the ‘messianic world’, which is to say, ‘the world of universal and full actuality.’ (Rochlitz, 230.) Benjamin believed that only through ritual, ceremony or an heroic effort of art could ‘lived experience’ be transformed into ‘true experience.’ Fallen history would then be redeemed, and those memories repressed by consciousness and culture would be restored to consciousness, in particular the socially repressed memories of the suffering and the struggle of the oppressed for progressive change.

Although he managed to avoid military service, Benjamin experienced firsthand the burden of involuntary memory in men returning from the First World War. Having lost any form of sustaining faith, these men nevertheless felt compelled to behave as if it remained intact. They tried to suppress their paralyzing experiences of shame, terror and impotence, all the while smiling and embracing the fiction that their experiences were an aberration. They became mute. Watching them shuffle back into ordinary life, Benjamin observed that ‘They were not richer in communicable experience, but poorer.’ (Rochlitz, 143.)

During the opera, Benjamin’s shade journeys, like Orpheus, into the shadow world to confront the demons of history. His experiences, in the words of the librettist, is one of

kataplexy, or ‘shock-induced paralysis’, a condition associated with psychological trauma and, in particular, with the trenches of WW I. For Benjamin and his colleagues,

kataplexy was one of the conditions of modernity. He was barely twenty on August 8th 1914 when he and his fellow students were told that two dear colleagues had gassed themselves in anticipation of the coming war. Benjamin’s biographer tells us that the traumatized students interpreted the suicides as a reasonable response ‘to the events that, with one fell swoop, had made them all aware of the meaninglessness of everything they had done until then....’ (Broderson, 70.) In a sense, Benjamin’s generation was sentenced to life in Shadowtime; their significant conversations were with the dead. In the libretto, Benjamin asks Scholem, ‘...how can language ever fulfil itself / As mourning?’ Scholem replies, ‘It is not the exterior expression / But the interior process.’ (Bernstein, 54-55.) Which is to say the process will never end.

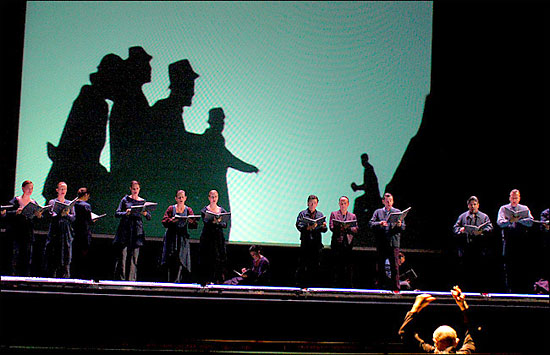

Shadowtime, by Stephanie Berger, New York Times, July 2005, Lincoln Center Festival, Rose Theater.

The war seemed to erase the storytelling that had once inspired and knitted society together. When the guns went silent the men went silent. ‘The enormous deployment of technology,’ Benjamin wrote, ‘has plunged men into an entirely new poverty.’ We can still witness the effects of this mechanized war trauma on men and women many generations removed from the trenches, and it’s increasingly clear that Europe, its fallen empires, its allies and its enemies, have been in a state of unacknowledged war trauma since 1914. Benjamin became disturbed during the 1920s by the rise of narcissistic populations that wilfully ignored not only the war but also the criminality of their leaders and their debt to those who fought for social justice. The self-regard of these populations, he was convinced, would condemn them to the same fate as their fathers, grandfathers and great-grandfathers. Only by telling the ‘history of the vanquished’ might the toxic cycle be ended. For Benjamin, art and poetry had the redemptive power to reveal suppressed histories, to release involuntary memory and return the experiences of the mute and the traumatized to the public forum where they could contribute to the Messianic project. In this sense, it is apposite to call

Shadowtime a work with redemptive power. By conducting Benjamin’s shade into the underworld to confront his and our cultural unconscious, Brian Ferneyhough and Charles Bernstein have made an effort to revive Benjamin’s project in our own time.

Benjamin would be discouraged by what he’d find if he returned today. Fundamentalist and pseudo-fundamentalist ideologies are taking hold once more. Ancient texts continue to be held hostage by political orthodoxies. Large nations attack small nations, spouting the most dreadful excuses for doing so. The world is weary again, which is as good as a lit fuse. In 1940, alarmed by Fascist victories and by what he perceived to be misplaced faith in progress as an historical norm, Benjamin famously declared that ‘the “state of emergency” in which we live is not the exception but the rule.’ (Benjamin, 257.) Even so, few could have predicted our current states of emergency when, in 1999, British composer Brian Ferneyhough asked American poet Charles Bernstein if he’d be willing to write a libretto centred on Benjamin’s life and texts. Bernstein completed most of the libretto within twelve months. The score developed over the next four years, and the opera was premiered in Munich in May 2004. Commissioned by the City of Munich,

Shadowtime is a co-production of the Munich Biennale International Festival for New Music Theatre, Festival d’Automne à Paris, the Lincoln Centre Festival, the 2nd Ruhrtriennale 2005 and Sadler’s Wells Theatre London. The work received its North American premiere in New York City on July 21st, 2005, as part of the Lincoln Centre Festival 2005. Considering the times, it’s exactly what the doctor ordered.

It would be difficult to find a more interesting collaboration. Ferneyhough, who was born in Coventry in 1943, is a prolific and celebrated composer of contemporary orchestral and chamber music. Expanding on the traditions of Webern and Boulez, his work is thought of as being demanding and rigorous — sometimes unplayable — yet the results are always intellectually and emotionally stimulating. Ferneyhough’s is a music of ideas, an inventive engagement with history and philosophy and human struggle. And while he has considerable experience with choral and vocal works, part of the excitement around

Shadowtime is that it represents his first full-length music theatre piece. Critics in Europe were deeply impressed by its early productions. Wolfgang Schreiber, writing in

Süddeutsche Zeitung, was impressed by its ‘pure artistic fervour’ and called

Shadowtime ‘a musical adventure of the most artful complexity, freed from all expectation...an apex of modern operatic artistry....’

Ferneyhough’s collaborator, poet Charles Bernstein, was born in New York in 1950 and has an equally distinguished career as a poet, editor, scholar and teacher with at least twenty-two books of poetry to his credit as well as collections of essays, collaborations with artist Susan Bee and others, and ongoing editorial/ curatorial work. He has collaborated with composer Ben Yarmolinsky to produce the libretti for three previous operas —

Blind Witness News,

The Subject: A Psychiatric Opera and

The Lenny Paschen Show — and has written a new libretto for composer Dean Drummond entitled

Café Buffe. Bernstein is executive editor and co-founder of the Electronic Poetry Center in Buffalo and a co-director and co-founder of PENNsound, a project dedicated to producing new audio recordings of poetry, preserving existing audio archives and making the downloadable contents of the entire archive free and available to the world. The superb text for

Shadowtime reflects his musical intelligence and his ongoing engagement with language, with the ear. Writing in

Music and Vision, Tess Crebbin has called

Shadowtime ‘the finest contemporary libretto that I know of.’

Bernstein and Ferneyhough call

Shadowtime as a ‘thought opera.’ Having heard and seen this remarkable work only once, I’ll try to write about it as comprehensively as possible but it’s a work of richness and complexity and cries out for more viewings. The libretto, thankfully, is available from Green Integer Books. In his notes on the opera, Ferneyhough writes that he asked Bernstein “to produce a text that at one and the same time would accept manipulation (permutation, repetition, mass exchange of segments) and be, in its own right, an independent poetic text,” and Bernstein has succeeded. (Ferneyhough, 3.) Musically, the scenes in

Shadowtime have been constructed so that they can be presented separately, which will enable disparate audiences to hear at least a little of this challenging score.

The opera unfolds for the most part by means of dialogues, monologues and interrogations, revealing Benjamin as a man divided. By the time he reached Portbou he was unwell, indigent and running for his life. He had seriously considered suicide at least once before. Ferneyhough’s occasionally searing, multi-levelled score, a work of gravity and thorny beauty, responds to and at times seems to represent fragments of Benjamin’s anguish. The Nieuw Ensemble Amsterdam conducted by Jurjen Hempel, and the Neue Vocalsolisten Stuttgart, superb musicians all, are clearly in tune with this intelligent and rewarding project. Hempel’s direction of the heady, complex score and the singers’ comprehension of the braid being woven forge a powerful urgency that transcends Benjamin’s tragedy to illuminate our own present — an era of self-inflicted amnesia and shameless Thumperismo. (‘If you can’t say anything nice, don’t say anything at all.’) Emmanuel Clolus’ sets, with lighting design by Marie-Christine Soma, are for the most part playful, childlike in a whimsical sense, and contain a deceptive air of provisionality, perhaps taking their reference from the nursery rhymes for Stefan Benjamin in Scene I that find their echo in the final scene.

In 1921, Walter Benjamin purchased a watercolour by Paul Klee entitled

Angelus Novus, and the image of this apprehensive, wild-eyed angel with its large head, sharp teeth, feathers for fingers and talons for feet became emblematic of his resistance to the destruction of the world he’d grown up in. In his ‘Theses on the Philosophy of History’, written after being released from a French internment camp in 1940, Benjamin described an idea he’d been harbouring for twenty years. Klee’s

Angelus Novus had come to represent the Angel of History: ‘His face is turned toward the past. Where we perceive a chain of events, he sees one single catastrophe which keeps piling wreckage upon wreckage and hurls it in front of his feet. The angel would like to stay, awaken the dead, and make whole what has been smashed. But a storm is blowing from Paradise; it has got caught in his wings with such violence that the angel can no longer close them. This storm irresistibly propels him into the future to which his back is turned, while the pile of debris before him grows skyward. This storm is what we call progress.’ (Benjamin, 257-258.)

The seventeen extraordinary musicians of the Neue Vocalsolisten Stuttgart who form the vocal heart of this opera represent the angels of history. Their appearance may seem curious to those who know Benjamin as a theorist of contemporary technology, yet angels were a necessary part of his vocabulary. Angels inhabit eternity, the realm beyond and the means by which we know the confines of time and fallen history. Benjamin would have been familiar with the work of the 18th century German philosopher J. G. Hamann who proposed an angelic language as the sacred text lying at the heart of all languages. For Hamann, speech was an act of translation ‘from an angelic language to a human idiom,’ and vestiges of this angelic language can be found in poetry alone. ‘Poetry,’ he wrote, ‘is the mother tongue of the human race.’ (Rochlitz, 31.) In

Shadowtime, Bernstein and Ferneyhough set out to fulfil the obligation imposed by poetry, to expose the act of translation that reveals, if only for a moment, a vision of the angelic, the Messianic world.

2.

Shadowtime is a haunted work, alive with spectral voices and a kind of contemporary ventriloquism derived from conversations, poems, numerical systems, rhymes, songs, blues riffs, homophonic translations, anagrams, Golem-speak, bureaucratese, word-order reversals, arguments, invented languages and philosophical/ theological dialogues in eternity taken from Benjamin’s texts and sifted through the folds of Bernstein’s allusive, inventive, sometimes witty and often sobering libretto. The opera adopts the Modernist strategy of attempting to know the world by creating a model of a mind perceiving the world.

Shadowtime is not a work about Benjamin’s mind; it

is — to the best of Bernstein and Ferneyhough’s abilities — Benjamin’s mind.

Bernstein has spent his career mining the fracture lines in linguistic practices. Along with a keen social and political intelligence, he possesses a generosity of thought and spirit that set him apart from many poets of his generation. His compositional strategies are never predictable — language that discloses has no brief with conventional syntax or cloying semantics — and in leaving his texts open to paragrammic disruption, plates shift, the borders between things are fundamentally altered. I’m writing this now on a clovery promontory on the west coast of Vancouver Island, and as I watch the fog sweeping in to conceal the forest in one moment, revealing it the next, I’m struck by the sleight-of-hand of borders.

Shadowtime is much concerned with borders, with the way in which something that’s ephemeral in one moment becomes deadly the next. One may intellectually collapse the borders between ‘God’ and ‘humankind’, between ‘life’ and ‘death’, between ‘language’ and ‘the world’, between ‘words’ and ‘music’, between ‘history’ and ‘the past’ yet, as Benjamin discovered, a border can also be unforgiving.

During the opera, Benjamin’s shade penetrates the border between life and death. He journeys into the underworld, into the world of

la mémoire involuntaire, to confront the shades whose lives brought torment into the world. Prior to his appearance a Lecturer/ Reciter (Nicolas Hodges) appears, a kind of Brechtian guide whose direct address suggests initially that he might wish to be our Virgil. The Lecturer seems to be the composer’s representative, establishing a rationalist, secular discourse and framework for Benjamin’s argument on behalf of the Messianic world, the potential ‘world of universal and full actuality.’

Walter Benjamin never strayed far from mystical and hermetic traditions, however, and so it’s Benjamin the alchemist we meet in Scene I in the body of lead he has failed to transform. Benjamin in Portbou saw himself as a failure. In his room in the Hotel Fonda de Francia he must have confronted God with a terrible decision. He would go no further. If, in the words of George Konrad, to live as a Jew is ‘to serve as the fulfilment of the obligation imposed by God,’ Benjamin chose on the night of September 26th 1940 to renounce his obligation, to repudiate his destiny, in effect committing a kind of deicide. ‘Existence burdened by God,’ writes Konrad, ‘this is the gift and the calamity of the Jews.’ Benjamin on that night saw only the calamity. (Konrad, .)

But I’m ahead of myself.

Shadowtime’s ‘story’ begins in fallen time. At the beginning of Scene I, Benjamin and his companion, Henny Gurland, have arrived at the hotel in Portbou. In their desperation, Benjamin (Ekkehard Abele), Gurland (Janet Collins), the Innkeeper (Angelika Luz) and a Doctor (Nicolas Hodges), confront the desperate situation. Life-sized puppets stand in for certain of the characters, including the Innkeeper, precluding role-identification with any of the singers. The opening begins conventionally enough, with pleading and refusing, but in eternity, or messianic time, only the present exists. To introduce this as a potential reality, the scene unfolds through layers that overlap in time and space. On a double bed downstage from the ‘hotel lobby’, as the hotel confrontation continues, a conversation from 1917 takes place between young Benjamin (Guillermo Anzorena) and his wife to be, Dora Kellner (Monika Meier-Schmid). We’ve entered ‘reflective time.’ The lovers reflect on their futures, discussing culture and prostitution, Eros and time, and the storms of the 20th century weigh heavily on their melancholy discourse and their premonitions of loss.

Superimposed upon this conversation, a quartet from the chorus begins to sing children’s rhymes dedicated to Benjamin’s son Stefan, born in April 1918. Overlaid upon these songs are two philosophical dialogues, one between Benjamin and his dear friend Gersholm Scholem (Andreas Fischer) followed by another between Benjamin and the poet Friedrich Hölderlin (1770-1843) addressed to Hölderlin’s pseudonym, Scardenelli (Martin Nagy) and to Hölderlin as a pseudo-Benjamin. The dialogues in printed form drop from the ceiling to the floor on unfurling Torah-like scrolls, framing the exchange in written text. The effect created by the words and music of each of these sub-scenes developing simultaneously, swelling and reaching for eternity and arriving at the line ‘Returning, forming into itself, coming home — ,’ was as primal, and riotous, and dangerous as eternity should be.

Benjamin and Scholem were friends throughout their lives, from 1915 until Benjamin’s death. When Scholem moved to Palestine in 1923 they continued to correspond and Scholem pleaded with Benjamin to leave France as anti-Semitism grew and that nation became more dangerous for Jews. They debated ideas throughout their lives, agreeing and disagreeing passionately with one another. Scholem was frustrated by Benjamin’s later, materialist, Marxist-inspired writings and, from the relative safety of Palestine, worried for his friend’s well being. Bernstein manages to catch the wild blend of concern and combativeness in this exchange, embedded in the flow and hurl of Scene I. (Bernstein, 53-54.)

SCHOLEM:

Self-deception can lead only to suicide

WB:

Better a bad revolutionary

Than a good bourgeois

SCHOLEM:

Yet I perceive the method

Refusing to be bound

By all that cripples thought

WB:

A way to think

Outside the self-enclosing circles

That bury us alive and make us

Deaf even to the dead

SCHOLEM:

This is why we sing the lamentations

This dialogue is a lament for language and for the world being demolished in the storms of the 20th century. Benjamin’s reply to Scholem, ‘Then mourning is a kind of listening / Where the dead sing to us / And even the living tell their stories,’ is swept up by the orchestra with the other choral layers. On occasion the singing is jerky, as if the performer is choking, which suggests an unbroken relationship between fearful breath and fearful body. Surtitles were necessary for identifying individual words in this unfurling musical/ linguistic Babel, although there were also moments when I found myself wondering about the quality of voice projection in the Rose Theatre.

Ferneyhough is known for provocative, complicated scores. Instrumentalists playing his music must sometimes make potentially sublime or devastating creative decisions because it’s physically beyond them to realize all that lies on the page. In a work like this, of course, the music is concerned precisely with what lies outside the page. The purpose of constructing overlapping layers of possible sounds — the artificial categories that divide ‘words’ and ‘music’ are shattered early on — is an analogue for building an altar: to summon the quick and the dead, the lost and the found, the loved and the betrayed, and to invoke the language of angels that existed before division, when love and the storm, eternity and the divine, were one.

The music in

Shadowtime is as daring and revolutionary as it must be if it’s to interrupt operatic conventions and inspire faith in the messianic cessation of history’s repressive continuum. The music is sometimes raw and angular, often brilliantly layered and always filled with rich complexity. The skill, the joy and the precision of Hempel’s Nieuw Ensemble Amsterdam was breathtaking. Scene II included an extended guitar solo by Mats Scheidegger which was meant suggest Gabriel’s wings. Ferneyhough’s note in the program helps illuminate his compositional approach:

The piece is made up of 128 small fragments, some of them lasting 2 or 3

seconds, some of them lasting maybe 15 seconds, which are played

continuously. I was concerned with making each of these segments just

understand it. We are continually being thrown back and forth like a ball

being exchanged, across a ping-pong table, between realizing we need to

attempt to understand the next texture, but not having entirely understood

where to place the previous texture or the one before that. Time in music

fails if it disappears without remainder into the musical experience.

It would be wrong to see

Shadowtime as an earnest or dour work. Faithful to Benjamin himself, there are flashes of humour throughout. Bernstein’s texts are often witty and playful as in Scene III where anagrams of Benjamin’s name playfully suggest esoteric Kabbalistic and numerological traditions. The music expands on the canon form throughout the scene and, in Ferneyhough’s words, ‘seeks to maintain a fragile sense of permanent recalibration of sense and mutual dissent by being divided into thirteen separate movements...which permitted me to continually re-initialize the power of auratic distance from movement to movement.’ (

Playbill, n.p.) Overall, the scene takes its pulse from Benjamin’s ‘Doctrine of the Similar’, which suggests that the sounds words make have their origins in the primal acoustic structures of the universe. The scene’s thirteen texts are based on prime numbers. Hidden relationships are revealed when one listens for sound — not meaning, when language is coaxed or shocked out of the anxieties of semantic monoculture.

Bernstein’s choice of nursery rhymes, word games and ‘primitive’ theatrical effects seems like a way of reaching back behind involuntary memory, beyond the war, beyond mourning, beyond suicide, to a pre-linguistic time of magic and belief. The comical, large screen shadow play in which cut-out silhouettes act out Benjamin’s and his companions’ journey up into the Pyrenees is deeply affecting and conjures up a pre-verbal, pre-electrical language. I was particularly moved during an extended video sequence showing pages of text in Hebrew and German with hands reaching toward the words. Fingers touched the words sensually, moving across the lines like angels of mercy, and the pages seemed to yearn for turning. Watching the hands reaching and the slightly murky image of the text, with its hint of the antique was, frankly, an erotic experience. Redefined by the orchestra, one arrives unexpectedly at a moment of transcendence, suffused with the Eros of redemption.

In Scene V, Benjamin’s shade finally enters the Underworld, or the domain of involuntary memory. He is interrogated by a nightmarish gang of historical and mythical figures represented by huge cut-out masks brought forward by the angels of history. The accosting begins with three red mouths, a headless ghoul, Karl Marx & Groucho Marx as two heads of the three-headed Kerberus, Pope Pious XII, Joan of Arc, Baal Shem Tov, Adolf Hitler, Albert Einstein and continues, finishing up with the Golem who speaks, appropriately, in a hilarious invented language. (Bernstein, 99.)

GOLEM:

Feefa, feega oow iggly?

WB:

If I submit then I die.

GOLEM:

Oraasamay dodofelliu ferumptious?

Benjamin’s moral seriousness, his courage, his insistence on civility, his open heart, his stubbornness are shattered by potty language. Little wonder the scene sends with Benjamin in despair quoting Heinrich Heine (1797-1856),

‘Keine Kaddish wird man sagen’ — ‘No one to say Kaddish for me.’ (Bernstein, 100.)

By the end of Scene VI the angels of history have turned the masks around to expose the apparatus that props them up on the stage. The lighting grid has dropped into view; the long Torah-like scrolls have fallen to the floor in a puddle and the veil that hides the backstage area has been lifted to reveal packing cases and the ordinary machinery of production. The Lecturer retires with Benjamin’s shade to the backstage area as if they’re waiting for something or someone. They make themselves awkwardly comfortable as the angels of history sing a children’s rhyme. (Bernstein, 109.)

Who’s to say, what’s to say

Whether what is is not

Or whether what is is so because

Is so because it’s not

We have arrived at unanswerable questions because we’ve arrived at the limits of fallen language. One cannot help but think of Lewis Carroll, another explorer of the paper, rock, scissors nature of language who set in motion a trip into the topsy-turvy underworld.

To call

Shadowtime’s stagecraft Brechtian is to suggest that it borrows ideas from Brecht’s concept of Epic Theatre (about which Benjamin was enthusiastic), but it seems more correct to say that this a work that’s aware of Brechtian gesture and interruption although it has little need of them. Scene VI, for all its deconstructive gestures, is deeply engaging and moving on every level. The machinery of the world stands exposed; that which once seemed substantial is revealed to be a brilliant façade, held together by baling wire, 2×4s, tape and hinges. The stage the world is is metal tubes, rubber wheels and shipping boxes. Day and night are tricks an apprentice is learning to do with lights.

The final scene, an epilogue entitled ‘Stelae for Failed Time’, represents ‘an elegiac solo by the Angel of History...it has two overlapping layers. The first is a reflection on time and uncertainty in the context of historical recrimination and erasure...The second layer is a reflection on representation.’ (Bernstein, 25.) The chorus members enter the darkened stage with candles. The music is ravishing throughout, reaching a sustained and peaceful conclusion. On tape, the composer reads Bernstein’s five nursery rhymes from Scene I translated into a language invented for the purpose. His voice on the tape is barely perceptible and the chorus members, when singing the same words, are singing ‘international phonetic alphabet transcriptions of my language sounds.’ (

Playbill, n.p.) Bernstein’s texts for Scene VII present searching, wistful, partly fragmented first-person monologues superimposed upon the five sequences of invented language. Loss, annihilation and the circularity of time haunt the ‘speaker’ who is both Benjamin and the Angel of History. At one point the text breaks into an awkward blues. References to a child’s game return, this time as a locus of cruelty. The voice seeks an escape from failed systems and tautological fantasies. (Bernstein, 118.)

This is my task:

to imagine no wholes

from all that has been smashed.

The final words of the opera challenge our dependency on representation for validation and evidence of being. What is the best ‘picture’ of a ‘picture’? A ‘negative’ is the answer, for it’s in the absence of representation that presence manifests itself, even in the absence of presence. The Angel of History provides at the final word, addressing the storm with what can only be called a kind of love. (Bernstein, 122.)

The negative pictures

the picture better

than the picture

just as I

picture you

without

ever having seen you

or touched you

as now you fall

from my arms

into my capacious

forgetting.

Ferneyhough’s sustained final chord seems to be suggestive of and open to the possibility of redemption as Benjamin imagined it, although not in the way Wagner imagined it. To cleave open and engage with involuntary memory, to embrace the messianic cessation of history, demands a courageous, radical

bouleversement of all that contains and controls us.

Shadowtime attempts this on both conscious and unconscious levels. In attempting to redeem Benjamin’s philosophical and theological achievements from the tragic biography, and by translating his words into poetic and musical forms that strive to become one with their angelic source,

Shadowtime becomes a work of forgiveness — the Kaddish Benjamin feared would not be forthcoming.

I would go a long way to see and hear this production again. Its complexity demands repeated hearings. There are extraordinary moments throughout, in particular Nicolas Hodges’ piano solo in Scene IV as the instrument is being pulled about the stage by the angels of history. His accomplished, thundering performance is both exorcism and invocation, a storm to counter and defeat the storm that batters the Angel of History. The stage direction by Frédéric Fisbach was clean and always inventive, never calling attention to itself, which is a triumph in a work that has a large cast and little apparent dramatic action. Wobbly moments were for me provided by Nicolas Hodges as the Lecturer/ Reciter. His role as declaimer seemed attached to, not intrinsic to the opera. I’m not certain, in fact, that the Lecturer/ Reciter has found his place in

Shadowtime; the role’s earnest presence added a layer of didactic solemnity and seemed to miss much of the wit and poetry that energizes this ambitious, absorbing and transcendent work.

Listening to the final moments of

Shadowtime, I remembered that one of the students with whom Benjamin shared a seminar in Munich in the autumn of 1915 was the poet Rainer Maria Rilke, who was forty at the time. As a young man, Benjamin felt a kinship with Rilke, who was also much concerned with angels. In

Letters to a Young Poet (completed by 1908 but not published until after his death in 1929), Rilke famously warned that when it comes to interpreting works of art, ‘Only love can grasp and hold and fairly judge them.’ If you are wondering why

Shadowtime may be a rare kind of masterpiece, it’s because during the creation and production of this bold ‘thought opera,’ Benjamin’s work and life were clearly grasped and held by loving eyes, hands and ears.

Bibliography

Benjamin, Walter. Illuminations. Ed. Hannah Arendt. Trans. Harry Zohn, New York: Schocken Books, 1969.

Bernstein, Charles. Shadowtime. København & Los Angeles: Green Integer Books, 2005.

Bowles, Paul. Sur Gertrude Stein: Entretiens avec Florian Vetsch. Trans. Michel Bulteau. Monaco: Éditions de Rocher, 2000.

Brodersen, Momme. Walter Benjamin: A Biography. Ed. Martina Dervis. Trans. Malcolm R Green and Ingrida Ligers. London: Verso, 1997.

Ferneyhough, Brian. ‘Music and Words.’

The Argotist Online. Ed. Jeffrey Side.

http:/ / www.argotistonline.co.uk/ Ferneyhough%20essay.htm

Konrad, George. The Invisible Voice: Meditations on Jewish Themes. Trans. Peter Reich. New York: Harcourt, 2000.

Lincoln Center presents Lincoln Center Festival 2005. New York: Playbill Incorporated. 2005.

Rochlitz, Rainer. The Disenchantment of Art: The Philosophy of Walter Benjamin. Trans. Jane Marie Todd. New York: The Guilford Press, 1996.

Scholem, Gershom. Walter Benjamin: The Story of a Friendship. Intro. By Lee Siegel. Trans. Harry Zohn. New York: New York Review Books, 2003.

Vancouver, B.C.

October 17, 2005

it is made available here without charge for personal use only, and it may not be

stored, displayed, published, reproduced, or used for any other purpose

This material is copyright © Colin Browne and Jacket magazine 2005

The Internet address of this page is

http://jacketmagazine.com/28/browne-shadow.html