Anne Waldman feature:

Return to the Contents list

This piece is about 5,200 words

or 13 printed pages long

Jena Osman

Tracking a Poem in Time:

The Shifting States of Anne Waldman’s “Makeup on Empty Space”

In an interview with Eric Lorberer of Rain Taxi, Anne Waldman says, “What I’m after is that wakeful state, through language that stays alive.”[1] What follows is an examination of how that concept can manifest by looking at two very different interdisciplinary incarnations of Waldman’s poem “Makeup on Empty Space.” In effect, language is kept alive here through a process of recycling, the text functioning as organic matter that reacts differently in different contexts. In both cases, the poem makes something happen — it leads to another idea, another work of art — a poem, a dance, a book, a day. Language “stays alive” by remaining flexible, functioning as a creative trigger that is open to collaborative change.

I. “dancing in the evening it ended with dancing in the evening / I am still thinking about putting makeup on empty space”

In 1983, Anne Waldman and Reed Bye collaborated with the choreographer Douglas Dunn on a piece called The Secret of the Waterfall. Waldman and Bye’s text served as the soundtrack for the dance, and the poets themselves were situated on stage in a provocative and oblique relation to both dancers and audience. The publicity materials for the first performance describe the connection between the six dancers and two poets:

The poets speak and enact a sinewy language that complements, intrudes upon, enters gracefully, resists, and underscores the very intense and intricate patterns and gestures of the dancers. These people seem to be spending the weekend together somewhere in the country and inside rooms, and move with and against each other through interesting combinations of speech and body. The poets are curious figures, human and formal, almost sculptural at times, whose presence lends a kind of tension and oddness to the situations. The dancers seem wonderful spirits visiting singly and in groups to incite or instruct or protect and be human too. Is there a cave behind the Fall?[2]

In the New York Times review of the piece, the trope of human sculpture repeats, but this time the objects are the dancers, not the poets: “The dancers present ‘options’ to the poets, who see them as collections of ‘shafts,’ ‘cogs’ and ‘sockets’ that are ultimately as liberating as they are strange.”[3] Both dancers and poets self-consciously point to their own humanity, falling in and out of social stances (both in physical gesture and in language), oscillating between formalized conceptual object and socialized domestic subject.

The Secret of the Waterfall was also adapted for video (directed by Charles Atlas on location in Martha’s Vineyard) with slight variations in the ordering of the text.[4] At the beginning of the video, the fact of the figure negotiating between the human and inhuman is made clear in the voiceover text: Waldman says “You have a robot of practical deeds.” Bye replies “And you have a rowboat hidden in the weeds.” This dichotomy is present in the interplay of rhetorical strategies throughout the poem. On the one hand the language is narrative and descriptive:

She turns her face aside from the dashing young man who has asked her to dance. They flop about. They are unencumbered. Or maybe it’s a juncture of two wills, buoyancy of arms, or two dispositions.

On the other hand, the poem “likes a cascade of words,” where the words are literally falling from their normative positions within the sentence into objects to be sounded out: “purse truce mountain cog flower,” “tile calorie glass orange river.” The poetic score for this dance maps a relation between the material and ineffable worlds.

At a certain point in the typescript of the text, it is indicated that Waldman will perform an “improvised” poem. In that position, in both the studio performance and the Atlas video, the improvisation is a version of the poem “Makeup on Empty Space” — a poem written around the time of the Dunn collaboration, but not specifically for it. In an email message, Waldman stated that she considers this poem a “successful ‘modal structure’ in that it is fluid, flexible, an ‘open system’ as it were....”

I am putting makeup on empty space

all patinas convening on empty space

rouge blushing on empty space

I am putting makeup on empty space

pasting eyelashes on empty space

piling creams on empty space

painting the phenomenal world

I am hanging ornaments on empty space

gold clips, lacquer combs, plastic hairpins on empty space

I am sticking wire pins into empty space

I pour words over empty space, enthrall empty space

packing, stuffing, jamming empty space

spinning necklaces around empty space

Fancy this, imagine this: painting the phenomenal world....

Waldman has described “Makeup on Empty Space” as coming from “the idea in Buddhist psychology that the feminine energy tends to manifest in the world, adorning empty space.”[5] In the context of the collaboration with Dunn, empty space is adorned with the bodies of the dancers who define it. But it is also adorned by language and a variety of rhetorics that include an activist metatextualism. Throughout the piece the poets seem to reflect on the dance performance itself, as well as their place in it: “Now they are stationary and we move among them, transparently”; “These figures are conceived in full light, more real than our reflections.” Although it might be assumed by an audience that poets in a dance piece would narrate the movement of the dancers around them illustratively, there is a less predictable interaction in this particular collaboration. The language (an act of mind) actually shapes the acts of the body.

Shapes in mind

a tree a dog a baby an arm a hammer

shapes in mind

a basket an anvil a watch a situation

shapes in mind

an argument a digression

sliding off a duck’s back

shapes like a curtain moving

[...]

shapes on the map

shapes in the mind

a tree a dog a chain a teacup an orchid

you stare at a page you hold a pen some of the time

look out the window

a flight of steps shaped in your mind

a photograph a blanket

putting words in the picture to alter sense[6]

The dancers respond to the language as much as the poets respond to the dance — but again, this response is not about illustrating the text. As Waldman put it in an interview with Lisa Birman, they “tried to see the parallels that exist or come about spontaneously between gesture and word that aren’t literal, that... create a third possibility.”[7] In other words, The Secret of the Waterfall was a semantic testing ground, where the languages of gesture and word could combine, clash, and generate beyond conventional mono-disciplinary possibilities. The final text and dance was a direct result of paying attention to the minds and acts of other artists. Such organic and generative dialogue is what marks another particularly unique collaboration in which Waldman was a central player and in which the poem “Makeup on Empty Space” was featured.

II. “there’s talk of dressing the body with strange adornments / to remind you of a vow to empty space”

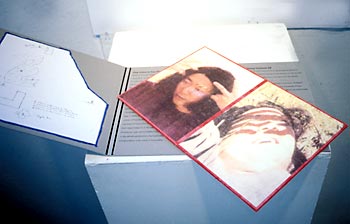

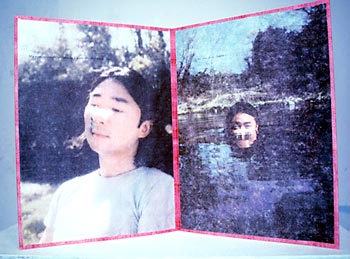

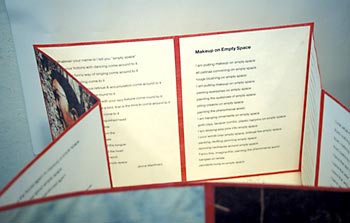

In 1997, the visual artist Richard Tuttle heard Waldman read “Makeup on Empty Space” at the College of Santa Fe. While listening to the poem, Tuttle began to imagine literal makeup designs. What followed from this originary moment is a limited edition artist’s book called One Voice in Four Parts. However, this “book” does not lend itself to conventional reading strategies. Tuttle describes the project as an investigation into the concept of “a book as theater.”[8] The results are a unique model for documenting an ephemeral creative process and performance.

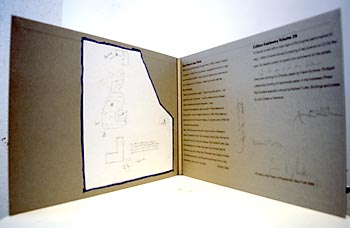

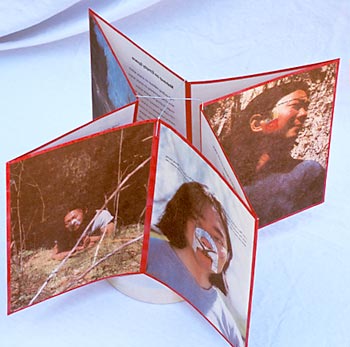

The creative process behind The Secret of the Waterfall can only be guessed at, reconstructed with the help of archival materials, the Atlas video, and the memories of the artists involved. The process of how the performance came to be (aside from the small metatextual references) is kept separate from the piece itself. In the Tuttle collaboration, process is in fact the piece; the product that evolved (which includes a CD, a video, and a screen-print letterpress insert that doubles as a textual sculpture when placed on a white circular stand — all housed inside a set of book boxes) is simply the residue of the actual work. Using his “book as theater,” Tuttle found a way to allow a time-based and context specific artwork to exist beyond its moment of actuality.

The book is really the capturing of one day — May 1, 1999 — when Tuttle, Waldman, and the Chinese actor and director Chen Shi-Zeng met at Gunnar Kaldewey’s fine arts press in Poestenkill, New York. As Tuttle describes the process on the inside cover,

Anne gave lines to Chen. We had the services of Yong Gui Ying to do makeup. Chen reacted to each idea then responded to it. All was videotaped and recorded with still photos by Juan and Zuleika Fall. There were many people involved in the whole production, but basically the book was to be a 4-part collaboration, one voice in four parts.

The video clarifies the logistics of how the piece was made. Tuttle made four designs to be applied one at a time to the actor’s face: a design for the eye, for the ear, for the mouth, and for the nose (in that order). The “four parts” of the project’s title refers to four conceptual movements that take place in four locations, each revolving around a different design, a different sense-organ. (At one point in the video, Tuttle parallels the parts with the seasons.) Once a design was applied, everyone involved moved to a particular location on Gunnar Kaldewey’s property. The jacket, or sheath, that protects the octagonal screen print includes a hand-drawn map that marks the four locations:

I. where actor lay in stones

II. where actor climbed the tree

III. where actor went in bushes

IV. where actor swam in pond

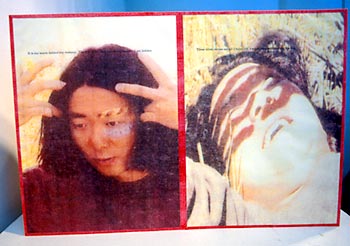

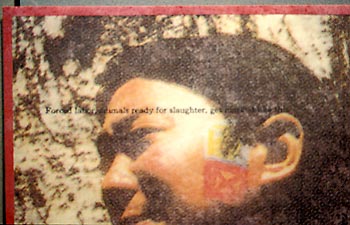

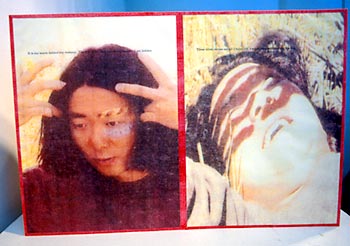

At each location, Chen described what it felt like to have the design on his face, what it reminded him of. Waldman then took his words as well as her own and “directed” the actor, giving him lines to say. After repeating the lines, the actor free-associated in response. Once a section was completed, the design was removed and the next applied, and the speaking/ directing/ associating procedure repeated with a new set of signifiers as a starting point. The flat and colorful pages of the book’s screen-prints represent scenes photographed and videotaped during each “part” of the day. Quotes from the day are printed across each image.

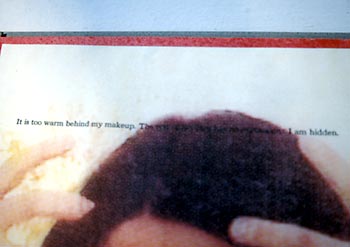

This text is often occluded — in the same way that some of the words are inaudible on the video because of ambient noise from helicopters and cars.

“It is too warm behind my makeup. The rest [...] I am hidden.”

“These silver stones are all I have left. I worry they will melt in the sun.”

The following transcription[9] gives the larger context for the “eye” images above and illustrates the collaborative relationship between Waldman and Chen:

Waldman: Maybe you could say something like “a certain kind of alienation... I feel the silver not the eye... the nose has run away... the forehead’s not necessary.”

Chen: A certain kind of alienation... the nose has run away... I couldn’t hear the eye... the rest of the face is disappearing.

W: I am only a certain kind of alienation. Say that a few times.

C: I am only a certain kind of alienation

[he repeats this several times.]

C: I feel like I’m disappearing in the sun. The sun is so strong. You worry about your silver stones melting. That’s the only thing I possess now.

W: That’s all you possess?

[the shadows of his fingers make zebra stripes across his face]

C: Those silver stones, they’re all I have left. I’m worrying about them disappearing.

W: All I possess.

[Click here for transcription of the entire section at the end of this document.]

When the four flat pages are folded out, they form an octagon. The reader can now see the interior, which is a letterpress presentation of Waldman’s poem “Makeup on Empty Space.” The octagon is then placed on the white stand, where it is fixed into a star formation with the help of a metal bracket.

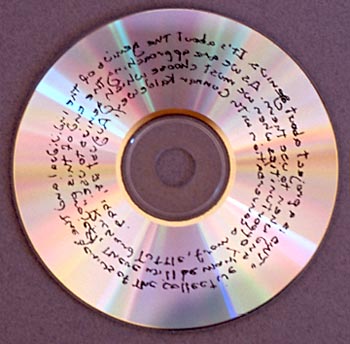

Tuttle has stated that one of the areas he was trying to investigate with the octagonal book form was the dialogue that occurs between inside and outside. In the same way that makeup provides a colorful exterior for a less knowable interior, Tuttle’s book structure creates a dialogue between its visual and textual materials. The audio CD also includes a double articulation. The first track is of Waldman reading “Makeup on Empty Space,” a poem which has been widely anthologized and is easy to find. The second track is of Waldman reading a new untitled poem consisting of language culled from the day in Poestenkill, never published and only appearing in this limited edition context. The CD itself is adorned with a spiraling quote from Tuttle:

This is a project about genius. It’s about the genius of the individual and the genius of the collective and when to use them. As we are approaching the end of this project, there will be many opportunities when we must choose which genius to use.

The word “genius” has a variety of definitions, ranging from the spirit of a person or place, to an actual spirit or person who influences another (as in a genii — or a director?), to a person with a singular talent or gift. All of these definitions make appearances during the course of the collaboration. Tuttle’s observation that this word — which is frequently associated with singularity or individualism — also has a collective meaning is an important one in that it emphasizes the double aspect which marks all collaborations. It also clarifies further the nature of the divide between interior and exterior knowledges.

The process of this collaboration — the conscious making of the mask or face, the deliberate feeding of lines to the actor, the actor serving as a material conduit for the lines (rather than “remembering” them in an act of fake self-expression) — is in an interesting conversation with Bertolt Brecht’s essay “Alienation Effects in Chinese Acting.” In that essay, Brecht states:

The artist’s object is to appear strange and even surprising to the audience. He achieves this by looking strangely at himself and his work. As a result everything put forward by him has a touch of the amazing.... The performer’s self-observation, an artful and artistic act of self-alienation, stops the spectator from losing himself in the character completely, i.e., to the point of giving up his own identity, and lends a splendid remoteness to the events. Yet the spectator’s empathy is not entirely rejected. The audience identifies itself with the actor as being an observer, and accordingly develops his attitude of observing or looking on.[10]

The concept of the actor observing himself and experiencing alienation from the self is evident throughout the videotape. While Tuttle’s design for the ear section was applied to Chen’s left ear, the following exchange occurred around the design:

W: A barred window or a cage.

C: A barred window, it’s almost like a cage; I have this fear of losing hearing once you put it on, and a similar structure, the window... you know how in the forced labor camp, they always have a symbol.

W: Like what?

C: There’s almost a sense of that...

W: A symbol. Which one — the top or the bottom?

C: Almost like when you send an animal to a slaughterhouse... you’re over two hundred pounds, you can go, that’s it. If you have the seal, that redness.

W: It looks like a gate for cattle.

C: Yes, they always have that, a gate, and it’s funny to have it at the ear... it’s very unsettling the color because it’s so bright. Inside the box are my skin colors.

and later:

W: Can you say “we didn’t send the animals to slaughter”?

C: We didn’t send the animals to slaughter... but I’m having a two slaughterhouse door frame on my ear.

W: Maybe say “it wasn’t forced labor.”

C: Feels like a forced labor, that shape... becomes identification.

W: Can you say “I lost my fear” again?

C: I’ve lost my fear. The only thing is hearing now. I can only hear. My ear was unnoticed until now. I’ve never paid that much attention to my left ear. It’s almost as if you stretch out your ear the way you stretch out your arm, just extending.

In company with Chen, the viewer of the tape also adopts the critical stance that Brecht claimed is essential if we are to renew our vision of the world around us. Ironically, this videotape may never be seen by many more than 15 people (since there are only 15 copies in existence, all in private collections), so the critical consciousness it encourages is kept “under wraps” in the box. There are 55 “regular” copies of the book that include just the screen-print images. In the print, the episode transcribed above is reduced to the following:

Forced labor, animals ready for slaughter, get... this

In this regard, the relation of inside to outside is troubling, in that the inside (or core) of the project can really only be understood by watching the video, and the tape is available only to “insiders,” the lucky 15. This artist’s book (as with most artist’s books) has a very private life; in some ways, it’s up to the poem to give the project a public presence.

Both Tuttle’s designs and the conversations with Chen echo Waldman’s “Makeup on Empty Space.” Lines such as “painting the eyebrows of empty space,” “painting the phenomenal world,” “I put my hands to my face,” and “I am starting to sing inside about the empty space” are literally enacted. The colors from the poem — green, red, blue, yellow, brown — are all present in the designs. Keywords such as “seductive,” “splash water,” “feminine deity,” “tiger” are also repeated and enacted.

Just as the original poem inspired visual imagery in the Four Parts collaboration, the visual imagery inspired a new poem by Waldman. That untitled poem can be heard on the CD that is included (another “private” part of the book), an excerpt of which is roughly transcribed here:

let the opera begin

did he breathe fire

did he walk on fire

did he battle his wits with ours

did we succumb to his wild guise

did he become woman in spirit day to day

moment to moment

struggle through song

for identity

take out the oracle bones

a shell of turtle

read these divinations

eye is arrow eye is window eye sees nothing

but desolate landscape he said barren empty beneath the

yes the eye

grey rocky cratered as a moon made and brow

above the brow

the furious stripes like bands and furs

this is all I have left little stones

why the eye hidden why am I hidden

why the eye hidden why am...

and I am only a certain kind of sun

and moon

alienation

ruse

choose the least vulnerable spot on the face and take your passion there

it might have an effect on the way the actor organizes

hearing a symmetry or asymmetrical

moonlight on the top a warning at the bottom

like fire she says

no no he contradicts her

almost a nightmare a board window he says

tell it, a forced labor symbol

a cage, a “send the animal to slaughter” symbol

and you want to climb a tree escape these guises

a face to hear by

the stepping and swaying

lady awaits you with bristles made of ferocious animal

she paints your desire she is silent yet recognizing the language yet

lime green out on a limb

an x for identity

struggle for survival

mute designs cry out for games

fire breathing stilt walking a way to overcome tigers

bristle

do not enter here

work along an avenue of indirect response

let go frame let go text the han dynasty horse of

awkward head awaits you

unsettled unsettling

wooden clappers meet in a dream

the song ends

we are bereft

guise

war interfaces with a human face

[Click here for entire poem

at the end of this document.]

The use of “Makeup on Empty Space” in both the Dunn and Tuttle collaborations illustrates how poetic language can work against fixity and singular viewpoints. From an “improvised moment” in a dance piece, to the trigger for an entirely different kind of collaboration fifteen years later, the poem is proof that “empty space” is what allows for provocative changes and collective discoveries. Waldman’s collaborative encounters illustrate how the poethical values of shifting states and non-attachment to permanent renderings can wake us up to language as it lives.

[Transcript of entire eye section of video]

I. where actor lay in stones

Chen Shi-Zeng: It’s very unsettling.

Richard Tuttle: Are you right handed?

C: I’m totally right handed. And it’s strange... this part of the body seems not very expressive anymore....

[he blocks off the made-up eye with his hands]

Everything becomes hidden....

[he hides his face with his hair, except for the eye]

Anne Waldman: Could you just say “I am hidden” about 10 times?

C: I’m hidden; I am hidden

[he continues to repeat while stroking his hair down over his face]

W: Maybe you could alternate “why the eye hidden; why am I hidden”

C: Why the eye hidden; why am I hidden.

[he repeats this phrase while pulling his hair back as in image above]

W: Say something about the light and shadow; either light above, shadow below, the shadow of the little stones, and there’s the shadow that the ground makes off the yellow bands. You could say “the shadow the brown makes of the yellow bands.” What do we call this? Particles?

C: Because it’s an eyebrow —

W: — there’s a natural shadow

C: — there is a natural shadow, because it’s almost like stripes, there is a relation on the movement itself.

W: Shadow above, light below...

C: I still don’t see the eye, I don’t see the eye at all.

W: Your eye is looking yellower.

C: I think maybe it’s some of the reflection. And yellow is supposed to have this light at least they think it’s the reflection of the sunlight, of the morning light, but it isn’t because of the shadow... there’s so much there... the proportion of the lower is larger than the upper stripe... somehow silver has more power... maybe it’s closer to here —

[gestures to his chest]

What do you think Richard? In a way I wish I could remove this.

[he gestures to the side of his face which is not made-up, blocking it off with his hands]

The forehead is totally unnecessary. I wish I can find a right angle to give, I couldn’t have a clear cut. Still there’s so much forehead.

[he lets two strands of hair intersect with the eye]

What you did was make the eye the most naked part; and when you have the black hair going through this sometimes disguises the eye and makes you want to see the eye more; otherwise the eye isn’t there. You said it’s like a moon surface?

W: Yes it reminds me of something crater-like, devoid of any kind of life, absent of green. What went into the colors when she made them?

C: White and black.

W: It’s incredibly silver; maybe it’s something that the skin does. I was also thinking of certain animal skins. Rhinoceros.

Gunnar Kaldewey: Also a giraffe.

W: Definitely. Tiger.

RT: Just now looking at the eyebrow and the hair... it makes the hair of the eyebrow look to be stones... difficult... and I find when we move or say something, we hold the eye in a certain way, I get excited, that looks right to me, true. If I had a camera I’d like to get this shot....

C: The funny thing is I lost physical sensation. The only focus is here, there’s no other sensibility that relates to it. It’s very much about here.

GK: When we look at you do you think we’re only looking at this?

C: Absolutely, I see everybody just look at this [he points to the eye]. I’m only having this relation with the sun.

W: So it doesn’t suggest any kind of character? It’s so abstract from that?

C: It’s a certain kind of alienation, it puts you actually out of the character. This is so much of the... I think about dark moon on this side. The only relation think about eyebrow, as Richard just said this is animal fur, not your eyebrow.

W: So it doesn’t resemble anything you’ve ever seen before?

C: It’s a very strange thing. [he gets up and sits on an overturned barrel] There’s no relation to anything. [he walks to rock] You have this rock and you have this... but I’m not relating.

W: Maybe you could lie down. Near the rock.

C: I’m trying to find some relation to this....

[cut to actor lying in grass; his hand is lifted up above his face to block out the sun]

W: Maybe you could say something like “a certain kind of alienation... I feel the silver not the eye... the nose has run away... the forehead’s not necessary.”

C: A certain kind of alienation... the nose has run away... I couldn’t hear the eye... the rest of face is disappearing.

W: I am only a certain kind of alienation. Say that a few times.

C: I am only a certain kind of alienation.

[he repeats this several times. cut.]

I feel like I’m disappearing in the sun. The sun is so strong. You worry about your silver stones melting. That’s the only thing I possess now.

W: That’s all you possess?

[the shadow of his fingers make zebra stripes across his face]

C: Those silver stones, they’re all I have left. I’m worrying about them disappearing.

W: All I possess.

RT: Maybe we should go to the next...

C: All I possess is my silver stones. [repeats]

W: Are you getting some of the rocks in the picture?

[Transcript of poem written as a result of the Four Parts day]

rune, you are guise of us signs on the face

become exorcist shaman receiver become dream lute accompaniment

to focus

of these bruises who initiate action

explanation of tree, stream, rock

or explanation of brown

maleness

hidden in an anticipation of who you might be

mere conglomeration of tendencies gestures into what

startle new acrobatic void

the Taoist priest arrives in ceremonial robes

let the opera begin

did he breathe fire

did he walk on fire

did he battle his wits with ours

did we succumb to his wild guise

did he become woman in sprite day to day

moment to moment

struggle through song

for identity

take out the oracle bones

a shell of turtle

read these divinations

eye is arrow eye is window eye sees nothing

but desolate landscape he said barren empty beneath the

yes the eye

grey rocky cratered as a moon made and brow

above the brow

the furious stripes like bands and furs

this is all I have left little stones

why the eye hidden why am I hidden

why the eye hidden why am...

and I am only a certain kind of sun

and moon

alienation

ruse

choose the least vulnerable spot on the face and take your passion there

it might have an effect on the way the actor organizes

hearing a symmetry or asymmetrical

moonlight on the top a warning at the bottom

like fire she says

no no he contradicts her

almost a nightmare a board window he says

tell it, a forced labor symbol

a cage, a “send the animal to slaughter” symbol

and you want to climb a tree escape these guises

a face to hear by

the stepping and swaying

lady awaits you with bristles made of ferocious animal

she paints your desire she is silent yet recognizing the language yet

lime green out on a limb

an x for identity

struggle for survival

mute designs cry out for games

fire breathing stilt walking a way to overcome tigers

bristle

do not enter here

work along an avenue of indirect response

let go frame let go text the han dynasty horse of

awkward head awaits you

unsettled unsettling

wooden clappers meet in a dream

the song ends

we are bereft

guise

war interfaces with a human face

are you letter or texture are you smooth or

escaped soldier disarmed for battle

a man in oily makeup is not to be trusted

a woman in red is generous a courageous woman in green comes from another century

the designs of the present are strange and provocative

where one becomes hunted

haunted

around 20th-century’s turn

haunted

about face

the sun

the moon

accessible to the initiate who escapes the text

imaginary whole phantom hovel

hallucinated doorway

imaginary hole

forces of memory and desire

tell it, the end of nature

tell it, the beginning of story

the warrior’s sad plight as deportee as refugee

tell it moon

a seal and a silver shield

protects the child

tiny

space

war

than

like

life

is

this is my meditation at first disturbed at first unsure of word

a sharp one word a blunt one to do

to do battle

this is my meditation an appetite for abstraction

a flower left to discover its lotus power might be too obvious in this seduction

this is my alienation

a sharp turn

a twist in sex

a torque above the face

its only projection

haunted

face

lantern

by chance we meet free-throw and find our way to innocence

expansion of a post-command

performance

ellipsis or

refracted light makes the environment

the book should tell us a philosophy

a boat should sink that philosophy

contradicted by the silliness by having something planted on the nose the face never dreamed or a sail on a

geometric body sea

enter the face the pond the boat flow of water words narration cross-eyed horizontal acts harbor

I’m putting makeup on empty space... world

do not neglect the droplet of water he said

know exactly what that means

this is my sun and moon

meditation she said and rune

ruse

guise

face you see the droplet of water is an expression of sadness and understanding that separation

let the boat face lantern lit from within go out

from its mooring

excitement

Notes

[1] Rain Taxi online edition, Winter 1998/1999. http://www.raintaxi.com/online/1998winter/waldman.shtml.

[2] Thanks to the archive at University of Michigan for providing these materials, as well as the original “script” for the dance itself.

[3] Reviewed by Jennifer Dunning, The New York Times, Friday, January 28, 1983.

[4] Charles Atlas and Douglas Dunn, Secret of the Waterfall, 1983. Produced by Susan Dowling for WGBH New television Workshop (Boston).

[5] Lee Bartlett, Anne Waldman interview in Talking Poetry: Conversations in the Workshop with Contemporary Poets. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1987. p. 262.

[6] Typescript, “The Secret of the Waterfall,” originals folder, 23 pp. University of Michigan Library Special Collections.

[7] “‘Surprise Each Other’: The Art of Collaboration” in Anne Waldman, Vow to Poetry: Essays, Interviews, & Manifestos. Minneapolis: Coffee House Press, 2001. p. 327.

[8] This quote was printed on the back inside cover of One Voice in Four Parts. Tuttle also states here that he wanted to “explore and explode the genre” of the artist’s book.

[9] There are only 15 copies of this edition that includes the video documenting this day. Many thanks to Anne Waldman who let me borrow her copy. Unfortunately, the sound quality on the video was very poor, so this transcription is only roughly approximate.

[10] Brecht on Theatre, ed. John Willett. New York: Hill and Wang, 1964. p. 92.

Acknowledgments: Many thanks to the following people for providing the rare materials and additional information to help me know these works: Anne Waldman, Douglas Dunn, Richard Tuttle, the University of Michigan Library Special Collections.

Jena Osman

Jena Osman's most recent book of poems is An Essay in Asterisks (Roof Books). Her book The Character (Beacon) was the winner of the 1998 Barnard New Woman Poets Prize. Other publications include Jury, Amblyopia, and Twelve Parts of Her. Her poems have appeared in numerous journals and her work was included in The best American Poetry of 2002 She is the co-editor of the literary magazine Chain with Juliana Spahr. She has received grants from the National Endowment for the Arts, The New York Foundation for the Arts, The Pennsylvania Council on the Arts, The Fund for Poetry, and has been a writing fellow at the MacDowell Colony, the Blue Mountain Center, the Djerassi Foundation, and Chateau de la Napoule. Osman received an M.A. in poetry and playwriting from Brown University, and a Ph.D. in English from the Poetics Program at the State University of New York at Buffalo. She is currently the director of the graduate Creative Writing Progam at Temple University.

it is made available here without charge for personal use only, and it may not be

stored, displayed, published, reproduced, or used for any other purpose

This material is copyright © Jena Osman and Jacket magazine 2005

The Internet address of this page is

http://jacketmagazine.com/27/w-osma.html