Michael Brennan

Last words: Tranter and Rimbaud’s silence.

This piece is 5,400 words or about 12 printed pages long.

Notes are given at the end of this file, with links that look like this: [71]. Click on the link to be taken to the note; likewise to return to the text.

Beware of Mallarme [sic]: he will send you mad. Heavy doses of Canabis Indica was the only thing that saved me from complete slavery to his pernicious doctrine in ’65, though traces of degeneracy linger on. Follow him far enough, and you’ll never write an intelligible word again. A quickly-chewed wad of Arthur is as good an antidote as any, though this remedy has its own contra-indications...ah, the danger of the blank page![1]

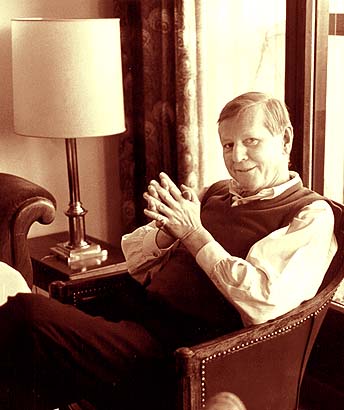

Hans Magnus Enzensberger, Munich 1984, photo by John Tranter

In regard to literary review and literary criticism, Hans Magnus Enzensberger once noted, ‘it’s difficult to get excited about something that’s simply wasting away,’ before continuing, ‘Literature has again become what it was from the beginning: a minority affair.’ Enzensberger’s polemic addresses a long history of the institutionalisation of literature and its criticism via both the academy and the mass media, noting the situation, ‘Today for every poet there must be approximately sixty-six academics employed in researching and interpreting him.’ He perceives the blunting of interpretative acuity as critics and then reviewers cater to the majority’s appetite for an easily digestible and then excretable moveable feast, and then lauds the demise of said criticism whereby literature has been returned to its stalwart, proper and apparently small audience. Enzensberger’s polemic concludes with the understanding that the century or more of literature’s and literary criticism’s ascension in the mainstream is at an end and (circa 1986 when the essay was written) we might be the fortunate generation to see writers ‘wipe off the representative mask which they wore so long.’

Enter John Tranter, among whose many masks representation has been perhaps the most consistently troubling one. Not, of course, of the majority, but of poetry: how and what it might represent in contemporary literary discourse but more troublingly in the aftermath of the twentieth-century. From the outset, Tranter has appeared discontent with the role of poetry in the contemporary world. While happy to talk about poetry, his and others, and to run a commentary on its development in the recent Australian context, Tranter seems less than enthused about poetry and its place in the broader scheme of contemporary experience. Perhaps one of Tranter’s most memorable and plainly spoken dismissals of poetry followed the release of At the Florida. When queried, ‘What next?’ Tranter responded: ‘Oh, I don’t know. I’m a bit sick of poetry just at the moment. I think I’ll take up photography again for a while, to clear my head. It seems that about every decade I get to a stage where I’ve been working at verse too hard for too long, and as a result I develop this revulsion against poetry: it appears artificial, pretentious, and affected to me, and the world of poets and editors and reviewers seems like a miserable swamp of dishonour and vanity.’[2]Interestingly enough, after noting the purgative qualities of going back to Graham Greene and Somerset Maugham, Tranter mentions the possibility of ‘a two hour radio play about Rimbaud in Wagga Wagga,’ and concludes in an aside, ‘but I’d better not say too much about that in case the good fairy grows jealous and abandons me and the inspiration leaks away.’ Perhaps jealousy and abandonment did follow as Rimbaud never made it to Wagga Wagga by way of a radio play. Or perhaps, it was just Tranter having a joke. In the brief poetic statement fronting his contribution to the anthology Landbridge, Tranter more recently commented, ‘I have no idea what my intentions are from day to day until I wake up. Generally I hope to live well, have fun, and write something adventurous. And I always keep this advice in mind, from a book called Screenwriting by Richard Walker: “When asked to offer his single most important piece of advice for writers, writer Tommy Thompson responded after a long thoughtful pause: Every day, no matter what else you do, get dressed.”‘[3] This is vintage Tranter, with the emphasis placed on the fun of poetry, effortlessly not giving too much away. For the light touch, the note of adventure made flippantly, and the habitually ironic treatment of the art of poetry, Tranter’s lack of ease with the idea of poetry as anything much more than a game is ever apparent. While akin to the jeu par excellence that finally caught in Mallarmé’s throat, it is one tempered by Tranter’s own peculiar, occasionally misanthropic take. A game not so sure of its end, not so arrogant or postured in its reverence of chance before experience. Tranter is perhaps a little more Rimbaldian than Mallarméan in his encounters with that beautiful trap of language and less devoted to the conceits of Poetry and the mysteries of language.

Tranter’s equivocal humour and take-me-or-leave-me irony is one of the joys and impasses of his work. It runs equally throughout his most polished and lyrical pieces, such as say ‘Debbie and Co’ or ‘At the Criterion’, as through his more experimental pieces of design and impersonality, such as the later computer generated cut-ups and more recent rewritings of poets such as Hölderlin, Rilke and Rimbaud. Tranter’s parody and satire of the presumptions and forms of poetry couple with an equally biting social commentary where an often isolated voice drifts more fatigued than perplexed by the deluge of the contemporary in its various forms, the rush and babble, the not quite broken lives, the migraines, sundowners, cars, migrants, through to the distant luminescence of America that underwrites so much of it. But for the retinue that inhabit his works, the stitched-together conversations that take place, Tranter as author remains scrupulously absent, registering style over content, language over experience.

For his early rejection of the understanding of poetry as an act of direct communication or address, from traditional forms of lyrical poetry, concurrent with a rejection of Humanism, Tranter’s work has been seen variously as a late-blooming Australian Modernism, an Australian response to Modernism and so a form of postmodernism, and even at one point a similar response to postmodernism (haphazardly suggested as post-postmodernism). Nevertheless, there remains in his work right up to Studio Moon, a troubled relationship and return, if only to further reject, those terrors of lyricism and Humanism that his poetry has gone to great lengths to satire, parody and reject. Even for the parodic and satiric intent, there is a greater interest in the design and design faults of language than a care for what the reader will take away. Tranter’s poetry does not seek to engage representation along humanist or lyrical lines, but rather to disrupt traditional poetic modes with an eye to press language beyond established modes of meaning and expression, creating a dialectically tensile relation between the two. Tranter explains at one point:

You can deconstruct things so much that they become meaningless, but then you’ve moved beyond meaning and the reader just throws you away. I like moving past meaning and then back towards it again. That movement is what gives the poem energy...

That need for meaning is built into the human brain, which means it’s built into the language systems we use — these are really only a projection of our brains, as Chomsky says. Language is an echo of our need to communicate, which is why it exists. I’ve never been interested in going totally beyond meaning, because there’s no point in writing. That’s not what poems are about, you might as well publish a leaf or a rock. But I am interested in the tensions you get when you go beyond conventionally expected meaning and come back again.[4]

It is curious to consider a work such as, say, ‘Enzensberger at “Exiles”‘ in the light of the quite conscious engagement of a dialectic on Tranter’s part, along with the broader discontent with the pretensions of poetry. With Enzensberger’s polemic in mind (which finds its counter-part in Susan Sontag’s earlier essay ‘Against Interpretation’), it would be counter-productive if not simply foolish to pursue a close textual reading of the poem here. Much better to give it in full, and allow the reader the pleasure of the text before then pursuing some lines of thought such pleasure and reading allow:

Enzensberger at ‘Exiles’

At the back of the bookshop a Karate expert

keeps a pot of coffee brewing, in the window

a man exhibits his bandages and the lights

flash red, amber, blue; all night long

the sex magazine quiz gets filled in.

What am I doing here? That cloud layer

threatens nothing, and speaks casually

of a distant beach; everybody’s laughing...

they trained beautiful men and women

to meet me at the airport, they

follow me around and buy me lunch,

they point out the misfits and the deviants

and keep me amused at parties where young men

fight and make up like emotional Brownshirts.

In Martin’s Bar the topless waitresses

are all sober, their perfectly matched tits

jump at the drunks while upstairs

a poet listens to the race results,

next door at The Balkan a cloud of burnt fat

gushes up the ventilator; these

are the good times, Australian style,

this has become a new vernacular

and waits my Adler to turn it into German.

Europe is a ruined Paradise buried under

books; here, nothing important was promised.

I’m drinking coffee and writing

in English on a piece of crumpled paper;

soon I’ll learn the native dialect and ask

Where are the ovens? Is it true that you never

Learned to kill each other? Are you happy?

This poem (along with ‘Leavis at the London’, ‘Sartre at Surfers Paradise’, ‘Foucault at Forest Lodge’ and ‘Roland Barthes at the Poets’ Ball’) operates through the initial tension created by the absurd displacement of the titular protagonist to various Australian destinations. Of the five poems, however, such absurdity is underwritten in ‘Enzensberger at “Exiles”‘ by the actual visit of said poet to the now defunct Sydney bookshop ‘Exiles’ once run by Nicholas Pounder. Of the five poems, ‘Enzensberger...’ is without question the most conventional in its construction of a narrative around the interrogation of the local Australian scene by the agents and emissaries of European culture. The plight of Barthes, Leavis and co tends toward disintegration as narratives of self, place, history and philosophy are jump-cut together or spool into each other creating a highly energised dialectical flow between meaning and absurdity, coherence and uncertainty. Enzensberger, on the other hand, unfolds a more rhetorical meditation on the collapse of dialectical History and the insouciant aftermath of life, literally, at the end of the world. The ‘good times, Australian style’ are unfolded tautly against the back of the ‘ruined Paradise’ of Europe. Germany’s Nazi past appears not simply as a part of dialectical history, but as a function of Enzensberger’s perception of the contemporary, the present scene being viewed in terms, similes and metaphors of the past. The present is seen only in terms of an impassable history.

The force of the poem lies in its expression not simply of a modern (or postmodern) malaise but in the wonderment of the final three questions. The first two questions express a supposition of norms given to and by the Modern, while the final question twists the notion of happiness (and perhaps, more broadly the ‘good’) around these norms, highlighting the extremity at which modern consciousness finds itself in the wake of the twentieth century. The possibility of happiness rests on and is perverted by the experience of recent history. Vague hermeneutics aside, the poem’s force lies in the speaker’s wonderment, and the energy contained and communicated by the establishment of a scene in which consciousness itself is dialectically played out in the poem. What it establishes, at least for this reader, is not so much the representation of Exiles and Enzensberger (though it does do this adroitly as well) but the appearance and experience of a consciousness. Yes, there is meaning and content to be had here, but perhaps more than that, one senses consciousness at work in the poem, forming and shifting against itself and against the scene it represents.

Every few years Tranter seeks to reinvent, or at least modulate, his poetry’s relation to representation. Tranter’s habitual recourse to irony and parody shields his work from a good deal of much purely experiential content and meaning premised upon a lyrical form of expression (in his words, ‘gush’). By ironising the lyrical modes and pretensions of the poet and poetry, in poems such as ‘The Poem in Love’, ‘Red Movie’ and eviscerating said roles in poems such as ‘The Alphabet Murders’, Tranter appears to clear a space where poetry is freed from the shadows of Romanticism and Humanism, traditions deeply compromised by twentieth century history (if not more simply by their own pretensions). If his work does not restructure poetic form in the light of a post-Holocaust consciousness attuned to the exponential and dehumanising processes of the technological and communications revolutions, if it does not seek to contain, express and comment upon the fragmentation of discourse and meaning that ensues, Tranter’s work does at least bear witness to the negativity of such things at work.

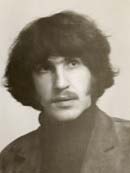

Rimbaud at seventeen, 1871,

a sketch by Cazals

Rimbaud has appeared as something of a figurehead for Tranter’s discontent with poetry for much of his career. Tranter offered the following understanding of Rimbaud’s initial influence, claiming it is ‘very necessary to have a violently opposed example to follow; and that’s where Rimbaud becomes very important for a lot of young poets. He is a rebel, an outlaw; he is French, he died eighty or ninety years ago and for those reasons [he is] a very good example of a writer who can be absorbed without being too destructive.’[5] This last point, that Rimbaud is not ‘too destructive’, is a curious one. Tranter’s various early references to Rimbaud and Mallarmé and the occasional other dead white French poet from the fin de siècle recall Eliot’s similar incorporation of the French poets as a radical example, drawing Tranter’s departure into line with Classical Modernism well after such things have had their day. For all of that, Tranter notes elsewhere, “‘One must be absolutely modern,’ Rimbaud said; and for what that’s worth as advice to other writers, it means that one must abandon Rimbaud himself as soon as possible. Rimbaud did it when he was twenty-one.”[6] While Eliot surfaces briefly and then sinks again without much of a trace, Tranter appears unable to bid Rimbaud a similar adieu.

The spectre of Rimbaud, the quintessential enfant terrible, haunts Tranter’s work throughout its various reinventions. In Parallax, Rimbaud appears almost omnipresent, shadows of his voice slipping into poems such as ‘Inertial Guidance’, ‘Childhood’, ‘Rain’, ‘Departure’ and so on, at times giving way to suggestions of Francis Webb. While Tranter’s subsequent collections move rapidly into an identifiable and unique style — Tranteresque as John Forbes cited it[7] or as Kate Lilley puts it elsewhere, ‘the trade-mark of the brand-name Tranter’[8] — the particular mixture of vagabondage, vitriol and dissatisfaction associated with Rimbaud’s poetry persist, slowly morphing with Tranter’s habitual lack of ease with poetry. Taking a quick sample: ‘Waiting for myself to appear’ draws back to ‘Le bateau ivre’, the river giving way to a highway, alcohol to heroin; ‘Conversations’ recalls the apprenticeship of the infernal bridegroom in Une saison en enfer, as does ‘Red Movie’ although perhaps ironising the limpid desire to shock of Tranter’s then contemporaries John A. Scott and Michael Dransfield. Tranter ironises the influence of Rimbaud (on both himself and his peers) in ‘Poem ending with a line by Rimbaud’. ‘The Poem in Love’, with its epigraph from the noted apocryphal French theorist Paul Ducasse, opens out to that other Symbolist Mallarmé, forming something of an either/ or with Rimbaud. The Alphabet Murders presents Tranter’s first sustained attack on the pretensions of poetry, playing out the abandonment of poetry Rimbaud undertook with Une saison en enfer, though as is apparent now being more play than abandonment. Leaping forward to the present, with the publication of Studio Moon, Rimbaud’s presence has neither lessened nor lightened (see ‘Brussels’ and ‘Rimbaud in Sydney’). Perhaps only next to John Ashbery’s equal importance, Rimbaud stands-out as a central and defining figure in Tranter’s imaginative landscape. Peculiarly, the French enfant terrible represents a point of impasse and definition to Tranter’s work. Rimbaud’s traditional assignation as exempla of both the poet-as-visionary and the abandonment of poetry in favour of experience, bring to light some of the difficulties and discontents that greet Tranter’s readers. The young French rebel appears more abiding than abandoned in an oeuvre that, like Rimbaud’s, is often at odds with itself and its place in the contemporary.

In the article ‘Feral Symbolists: Robert Adamson, John Tranter, and the Response to Rimbaud’, David Brooks claimed, ‘the Tranter style — readers have come to know’ emerged from a period of crisis that began in Singapore in 1971, which The Alphabet Murders dramatised and to which ‘Rimbaud and the Modernist Heresy’ gave voice at the end of that decade. Brooks contextualised the crisis in terms of yet another Tranter acknowledgment of Rimbaud’s influence:

John Tranter, c. 1969

‘When I was very young I believed the role of the poet was rather visionary and prophetic. I was reading a lot of Rimbaud at the time and I thought the role of the poet was to see things that ordinary mortals were unable to see — relationships between things and patterns of meaning in the universe — and convey that to a general readership in very intense ways. I really don’t think that’s the case any more and that belief faded during the sixties.’

What comes to be rejected through this ‘crisis of faith in poetry’ is according to Brook’s terminology the ‘“religiophilosophical” account of poetry and the poet’s role.’ Brooks draws out the notion of a crisis of faith in poetry across a swathe of poets (Rimbaud, Mallarmé, Rilke, Slessor, Hope, McAuley, and Tranter) arriving at the possibility that ‘Loosely, we might say that the continuation of the poets’ writing depends upon their metaphysics ability to survive this crisis — its capacity to adjust and be tempered by it — or on their willingness and ability radically to rethink their own styles, to find a new basis or new rationale for their writing.’ With regard to Tranter’s own rethinking and rejection of a ‘visionary’ or ‘messianic’ poetic, Brooks states: ‘John Tranter, in his own turn, could be said to redeploy Symbolist techniques to secular and existentialistic — perhaps I should be more cautious and simply say Classical, or Classical-Humanist as versus Romantic — purposes.’ Brooks hesitates around claiming poetry as an ‘alternate or surrogate metaphysic’[9] for the feral symbolist in crisis. Rather he sees ‘ironically’ Tranter may be seen ‘to be arguing for and writing a kind of secularised, ironised and existential poésie pure, and so to be carrying on the Mallarméan enterprise without Mallarmé’s faith in Poetry itself as a surrogate metaphysic.’[10] Brooks is right to be cautious.

Caution is by and large a trope in much of the criticism on Tranter.[11] There is in Tranter’s work as a whole, a continual and ongoing process of reinvention, a process dissonantly attuned to the Modernist demand, make it new. Tranter speaks of this process of reinvention in terms of abandonment, of escaping rather than working in the bounds of a particular style, ‘I’m trying to leave a style behind me, I think, rather than trying to find one ahead of me.’[12] In this, Tranter appears to stress that he operates in reaction not simply to broad literary traditions, or the poetics of the moment, but more closely in relation to a personal style and its disruption. Elsewhere, he can be critical of poets whose career is based upon a late-Romantic relation to ‘voice’, where each poem operates as a part of an organic whole centred on a particular speaker’s experience. Tranter’s trajectory is drawn across a demand to force his expression beyond the confines that might be set for it, by critical or literary discourse and by the very internal motivations, preoccupations and rhetoric that establish themselves in the act of writing and over a career in writing. A large part of his work has become the recurrent escape from particular styles through which a subject might slowly come into focus. This may well be akin to Mallarméan impersonality, yet as with the Mallarméan enterprise of purification, the final irony that the poet writes the work (even for all the tools and tricks he might place between his self and the page, such as cut-ups, orchestration, computer generation) is inescapable. Unlike Mallarmé, Tranter’s understanding of the trap of language is more mathematical than mystical. Whereas Mallarmé’s work demands a leap of faith in the negativity of language and a basically religious sense of poetry, Tranter’s work seeks out a rigorous excoriation of language coupled with a willingness to allow for the existential to enter into poetry, so long as the warping effect of language upon meaning, and the consequent re-evaluation of both language and the existential, take place. Tranter does not place singular emphasis upon language or the existential elements of a poem, rather allowing them to operate and form meaning and coherence through relation. At the heart of his poetic, is a keen ability to modulate an aspect of either the existential or linguistic/ poetic code in a poem, so as to effect and warp the entire field of relations. His is not a poetry that decodes experience or language, but further encrypts, hacks and overlays codes. It is a poetry which does not crack code. Where the possibility of absolute value is removed from the field, such as Mallarmé placed upon Poetry, then the interdeterminacy of each part of the field allows for any number of severe or subtle effects to the scene/ expression the poem/ poet creates. Tranter notes in relation to his use of cut-ups: ‘part of the exercise is to attain a kind of meaning by using materials that have had their meaning disrupted completely. So it’s to drag a group of words from one state into another state without altering them too much that I find interesting and exhausting.’[13] Much the same might go for his general trajectory from style to style, from the new to unknown.

Tranter is even more dangerous to a reader arriving to his poetry via Humanism or Metaphysics. ‘Rimbaud and the Modernist Heresy’ is Tranter’s sustained plaint to the young poet-revolutionary and stands out for its discursive approach to the difficulties the poet encounters when attempting to find coherence between the unfolding of poetry and history, the difficulties the speaker faces in adopting the role of poet, and of believing in poetry. Tranter signals at least some part of the importance of Modernism to his response to Rimbaud most simply and obviously through the piece’s title and the presence of the epigraph taken from Eliot, but presses beyond this, contextualising his plaint in terms of a consciousness of the atrocities of the second-half of the Twentieth century. While Eliot’s malaise surfaces on the back of the conclusion of the ‘war to end all wars’, Tranter’s response entails not simply a post-World War II, post-Holocaust consciousness but one in the midsts of the radical shifts brought about by technological innovations of the second-half of the Twentieth century. At least part of the poem — which Tranter revised over the course of the 1970s — was written while the American War in Vietnam was being waged. Technological innovation in representation and communication on one hand and warfare on the other found an exempla in the televisation of the American War, and forms a backdrop to the anger at the heart of the poem. Rather than malaise, Tranter’s speaker registers anger at the absurd propensity of humans to seek out annihilation. In a series of notes to Rimbaud interspersed throughout the sequence, the last one hundred and eight years of poetry’s history — ‘since he told Banville to adopt/ the telephone pole as his iron-voiced lyre’, and so presumably the history of poetry’s modernity — is glossed and updated, its pretensions and aspirations coupled with those of the poet, writ ludicrous against the backdrop of a century of wars. The crisis registered in ‘Rimbaud and the Modernist Heresy’ is not simply a rejection of metaphysical pretensions or the exculpation of poetry’s pretensions. Such rejections had already been established through earlier works by the time of ‘Rimbaud and the Modernist Heresy’, and rather than repeating, Tranter appears set in this long poem to exorcise himself of the lingering taint of humanism to be found in a secular and existentialist world view. Equal to Tranter’s lack of faith in poetry as a ‘surrogate metaphysic’ is his lack of faith in any form of redemption for the human and its varied projections through language and the real. Rather than geared for survival, Tranter’s poetic appears geared toward a permanent state of flux, forcefully and consciously engaging itself with the negativity of language and the representation of said negativity’s counter-part easily found in the world (either by way of the quotidian and minituae, or a broader Hegelian view of History’s unfolding as complicated by late twentieth-century thought and indeed experience).

So what of Rimbaud, this spectre shadowing Tranter’s work right up to his most recent? There seems a curious confusion with regard to Rimbaud throughout much of the commentary on Tranter and his work, as Rimbaud is often miscast as exempla of the poet-visionary and much of the demand to abandon him stems from the desire to repudiate poetry as incantory, magical, visionary. Susan Sontag notes, ‘The earliest experience of art must have been that it was incantory, magical; art was an instrument of ritual. (Cf. The paintings in the caves at Lascaux, Altamira, Niaux, La Pasiega, etc),’ before continuing, ‘The earliest theory of art, that of the Greek philosophers, proposed that art was mimesis, imitation of reality.’[14] It is at this threshold between alchemy and mimesis that Rimbaud may be seen to have abandoned poetry. It is a mistake or a cruel misreading to allow Rimbaud to stand simply as the archetypal poet-visionary, when the lion’s share of his work is a prodigious excoriation of just such a conception of the poet’s role. ‘One must be absolutely modern,’ and for that one must do away with art, not simply its visionary guises, but its humanist, existentialist, secular, mimetic, parodic, and revolutionary guises as well, to become ‘the master of silence.’ Tranter was never in any danger of succumbing to late-Romanticism nor for that matter to the excesses of postmodernism, but it is perhaps the silence of Rimbaud (not the silence that he represents), the absence his work presents by its end, that haunts Tranter’s own work.

Central to ‘Rimbaud and the Modernist Heresy’, and I would cautiously suggest, central to the anger that underwrites much of Tranter’s work, is a conscious sense of the absurdity of poetry’s contemporary existence. As with Rimbaud, poetry becomes an exercise of the intellect attempting to push language, that projection and project of the human brain, to a realisation of meaning’s and absurdity’s interdependence, and the fragile grasp of the human on dialectical negativity, on the very way its history, the history it creates, unfolds. By rejecting the visionary and metaphysical, and zeroing in on mimesis, poetry becomes a playground capable of engaging a contemporary history as voided of meaning. Not simply a game of linguistic relativity, or an excessive regard for the arbitrariness of signification, what might be seen in Tranter’s work is a demand and a desire to return through poetry not to meaning but an experience of world, of consciousness and language forming a world, coupled with the recognition that the ‘world’ formed is very much the ‘placeless elsewhere’ or ‘imageless universe’ Rimbaud spoke of. This is not a redemptive vision vested in possible metaphysics or the ineffable nor is it a resort to existentialism nor is it a cry for ontological help from the nearest phenomenologist to hand. It is a movement of poetry toward relation, of the modernity Rimbaud suggested, with the absolute of the end of absolutes. ‘No more words.’

What is this end, this ‘absolute’ modernity? To return to Rimbaud, ‘it will be permissible for me to possess truth in one soul and one body.’ It would be simple, reductive, to read this as a visionary demand. Such a reading counts on misreading the abandonment Rimbaud undertook, on not hearing the adieu of Une Saison en Enfer, and to end confined to the young poet’s letters of 1871, the lettres du voyant as they are called. Nor is this a reaffirmation of the Platonic syntagma, it does not give itself to a neoplatonic gnosticism. It is not à Dieu. Rimbaud addresses himself to the future, to what is yet to come. At the point he bids poetry farewell, and does so without irony through poetry, he arrives at a limit, at the threshold before which monstration is yet to begin, at the threshold where the future is yet to uncover its poetry, its poeisis, its terrible making. Tranter is right to state the young French poet had no idea of the century that lay just beyond the limit he set. As with Rimbaud, below the laughter there is a desperation at work and for all its ironised rhetoric it would seem a genuine claim of Tranter’s speaker that ‘Arthur, we needed you in ’68!’ At the other end of the century, it’s difficult not to feel the same exasperation if not despair as Tranter’s speaker and wonder at what point to abandon poetry.

The danger is to look too far, to demand too much. Rimbaud’s absolute modernity rests on and at the ‘step gained’, that is the limit of the present (the step, ‘pas’, being both progess and negation). It is there that ‘it will be permissible for me to possess truth in one soul and one body,’ much as it is there that history, arrested and removed from its dialectic, plays through meaning to meaninglessness. It is there that the incantory becomes the mimetic and magic is lost, but it is there that poetry must be abandoned to await the future that is always coming in. For all the strategies of escape and surface in Tranter’s work — carefully tuned, sharp so as they make you laugh and smart, diabolical perhaps, polished certainly — that resist interpretation as much as they resist meaning up to a point, it is hard not to miss that hesitation before giving up on meaning, that gesture towards the limit that rests at the limit. While writing this I have had the following passage from Sontag’s ‘Against Interpretation’ in mind: ‘Ideally, it is possible to elude the interpreters in another way, by making works of art whose surface is so unified and clean, whose momentum is so rapid, whose address is so direct that the work can be… just what it is.’[15] This speaks to me precisely of Tranter’s work (a poem such as ‘Lufthansa’ exemplifies such unity, precision and momentum). There remains, however, that movement back from the surface, that spectre of Rimbaud and the inability to abandon meaning completely but to push language to a limit, yes its breakdown but also its beginning in the present, beginning toward the present with the foreknowledge of its end. For Tranter, another style to break from, unravelling dialectical energy, negativity given its reign. Perhaps it is true that interpretation suggests a discontent, a desire to replace one thing with another. I have no doubt, much better to read Tranter than to interpret his work or read criticism on it, to listen to the surfaces and wait for meaning to expand and contract in its curious ways. For now, for the pleasure of reading it, it will be possible to end with a passage from a careful reading of Rimbaud that pursues poetry and interpretation alike, a passage that offers insights into Tranter’s work without ever having approached it:

Furthermore, what says adieu to this knowledge and its vision is, identically, what says adieu to poetry. In the farewell, poetry is not elevated, sublimated, into a higher philosophical truth. There poetry does not become more true; it is posed, left, abandoned on this edge, on this limit, whence a future possession is only named, almost brutally only named, as the indiscernible, unforeseeable, unsignifiable yet-to-come of poetry’s last words.[16]

Notes

[1] John Tranter to Robert Adamson, addressed and dated ‘70 Greenwood Avenue/Singapore 11/18 May more or less,’ 1971. Robert Adamson correspondence 1971-1977, NLA MS 5713 Box 3 Folder 19. This is the letter Adamson mentions in Robert Adamson, ‘Robert Adamson and the Persistence of Mallarmé: An Interview with Michael Sharkey’, Southerly 45, Number 3 (1985): 310.

[2] John Tranter, ‘A Conversation with John Tranter’, Antithesis, Volume 7, Number 1 (1995): 159.

[3] John Kinsella (ed.), Landbridge: Contemporary Australian Poetry (North Fremantle, FACP, 1999): 294.

[4] Erica Travers, ‘An Interview with John Tranter’, Southerly, Volume 51, Number 4 (1991): 18.

[5] John Tranter, ‘Four notes on the practice of Revolution’, Australian Literary Studies, Volume 8, Number 2 (1977): 160.

[6] John Tranter, ‘Four notes on the practice of Revolution’: 133.

[7] See the late, great John Forbes, Collected Poems (Blackheath: Brandl & Schlesinger, 2000): 161.

[8] Kate Lilley, ‘Tranter’s plots’, Australian Literary Studies, Volume 14, Number 1 (1989): 41.

[9] David Brooks, ‘Feral Symbolists: Robert Adamson, John Tranter, and the Response to Rimbaud’, Australian Literary Studies, Volume 6, Number 3 (1994): 282.

[10] Brooks, ‘Feral Symbolists’: 281.

[11] Two clear examples of caution in reading and interpreting are also two of the best pieces of criticism on Tranter’s work. See Andrew Taylor, ‘John Tranter: Absence in Flight’, Reading Australian Poetry (St Lucia: University of Queensland Press, 1987): 156-170 and Noel Rowe, ‘The Unsure Reader’, Modern Australian Poets (Sydney: University of Sydney Press, 1994): 36-46.

[12] Stephen Craft and Helen Loughlin, ‘An Interview with John Tranter’, Hermes, Number 7 (1991): 40.

[13] Craft and Loughlin, 41.

[14] Susan Sontag, ‘Against Interpretation’, Against Interpretation (New York, Picador, 2001): 3.

[15] Sontag, ‘Against Interpretation’: 11.

[16] Jean-Luc Nancy, ‘To Possess Truth’, The Birth to Presence (Stanford, Stanford University Press, 1993): 292.

Michael Brennan

Michael Brennan was born in Sydney in 1973. His first collection, The Imageless World (Salt, 2003) was short-listed for the Victorian Premier’s Award for Poetry and won the Mary Gilmour Award. Brennan received the 2004 Marten Bequest for Poetry and is the Australian editor of www.poetryinternational.org. He currently lives in Nagoya, Japan where he is a lecturer in the Department of Asian Studies and Foreign Languages, Nagoya Shoka Daigaku.

it is made available here without charge for personal use only, and it may not be

stored, displayed, published, reproduced, or used for any other purpose

This material is copyright © Michael Brennan and Jacket magazine 2005

The Internet address of this page is

http://jacketmagazine.com/27/bren-jt-ar.html