JACKET INTERVIEW

Ken Bolton

in conversation with

Peter Minter

12 October 2004 to 29 April 2005

Born in Sydney (1949), Ken Bolton lives in Adelaide, South Australia. He is a poet, art critic, publisher, and editor of the literary magazines Otis Rush and Magic Sam. His major publications include a Selected Poems (Penguin/ ETT) and Untimely Meditations (Wakefield Press). With Melbourne poet John Jenkins he has also published a great deal of collaborative poetry including The Wallah Group (Little Esther) or Nutters Without Fetters (Press Press). Ken Bolton edited Homage to John Forbes, published by Brandl & Schlesinger in 2002. He lives with author Cath Kenneally.

This interview was was commissioned by John Tranter for Jacket magazine. It is 18,500 words or about 40 printed pages long.

¶ PETER MINTER: You were born in Sydney in 1949, a real baby boomer baby! I’d like to begin by asking about your life experiences in the 1950s and 1960s: where you grew up, your family life, how you were turned on to art, music and poetry — any significant moments or people you now feel were catalytic in some way.

KEN BOLTON: I grew up first in Mosman, which I don’t remember very well. When I was about nine we moved into a war-service home in Warrawee on the North Shore: the street was a muddy path in the bush when we arrived and my dad cleared the land, though it was asphalt by about the time we moved in. The bush was great for spending time in, never absolutely boring. My parents separated when I was eleven and my father brought up my younger sister and me.

There were no books in the house, aside from the phone book and the Yates Garden Guide. No art either. I regularly came second last at school during the Mosman years but when we moved I left the nuns at Mosman for St Leo’s College, Waitara, and I must’ve started paying attention — suddenly I started doing well.

I think my mum’s leaving might have thrust me into isolation and self-involvement — ‘separations’ were less common then and slightly scandalous — but maybe it was coming anyway with the hormones. I started reading voraciously, going quickly from science fiction and Ian Fleming to Penguin paperbacks and their modern classics particularly, which I thought a guarantor of adult sophistication. I also used Walter Allen’s survey of the modern novel to direct me almost exclusively to cult, odd, left-of-field novels. So I was oddly well-read, having skipped everything canonical and enjoyed the curiosities. I’ve never read F. Scott-Fitzgerald, but by eighteen I had read all of Nathaniel West. That sort of thing. While of course feeling I knew ‘about’ Fitzgerald. I wrote comic, parodic ‘novels’ in school. I didn’t start trying to write poetry till my third year of university, I think.

¶ Pete: And visual art?

Ken: I had no connection with visual art. I remember I went to the Art Gallery one weekend. It was raining and I found myself there, and thought — ‘That must be the Art Gallery!’[1] In the 1960s it was a very dull museum, I’ll tell you. I didn’t go back.

Years later I began studying Art History at Sydney University. I kept failing one subject (anthropology) and they wouldn’t let me even try for it a third time. I had to find another subject, and I chose Fine Arts — I’d been looking at art books in the library and very much liked De Chirico and Munch. Anyway, I loved it. I tutored in it for a while and very nearly became an Art Historian. I found Donald Brook a very influential teacher at university, a philosopher and critic amongst the art historians.

At school a number of teachers probably looked out for me — and I liked a lot of them and owe them a great deal of gratitude — but it was then a very unacademic school. We were all poor, or poor-ish Catholic kids of no culture. In my final year only one person matriculated to university, for example, and that was a university in the country! The next year — I repeated the year — there were half a dozen of us made it. The demographic of the school was changing. I think soon after it rapidly became an expensive school and began performing. But in my time it had very big classes, quite a proportion of unqualified teachers. It was small, though, and took you in from lower primary right through to the final year: you felt very secure — you’d been there all your life, everybody knew you and all that. I thought I’d probably work in a bank or be a teacher, but that going to university was the idea — because then you didn’t have to do anything for three or four years! (Just read books — my idea of Life.) This has sort of been my attitude ever since unfortunately.

¶ Pete: So how did you come across poetry? Who did you begin reading, and what was your first poem?

Ken: I was in high school in the sixties. The poetry that seemed interesting was Donne and Eliot. Though I remember we read Pope and Coleridge and Tennyson, and they were big on Hopkins because of his religious nature. I liked talking about poetry in essays and in class, but I didn’t expect to be writing it. I liked that you could analyse it and see how it worked. We were never asked to try to write any.

I started to write poetry in my early twenties while at university. I read around to see what was supposed to be contemporary. Sydney University taught introductions to Graves, Roethke, Levertov, Williams, and Plath, and I found Larkin and Davie. But at some stage I met other poets and would-be poets and would have discovered back issues of New Poetry around that time — which led to the then more current stuff. It was quite a while before I wrote anything very interesting, though by about 1973 I was probably committed to it, despite not thinking very much of the poems I had so far written.

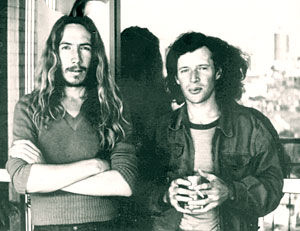

Ken Bolton, Arcadia Rd, Glebe, Sydney, 1974, photo Gabrielle Dalton

I don’t remember and don’t want to remember the early poetry. One was a set of scenes, views, walks, and thoughts, on cards that could be shuffled. It was slightly Edwardian, like TS Eliot meets some kind of Cubism: bleak and bravely disappointed. Well, that probably indicates my animus towards it. It was set in Glebe, around the railway viaduct and park and canal.[2] Earlier I’d lived in Harris Street and loved the trains slowly shunting and clanking late at night amongst all that ancient industrial architecture, under the full moon, with the little fluorescent Toohey’s man above the brewery, visible in the distance from my balcony, raising his glass, steam drifting over him.[3] I was so happy to be living away from home. You should ask me another question before more comes back to me.

¶ Pete: The early 1970s were an especially productive time in Australian poetry. The so-called ‘so-called’ Generation of ’68 had established themselves, and a number of important anthologies had appeared — Tom Shapcott’s Australian Poetry Now (1970), Alexander Craig’s 12 Poets 1950–1970 (1971), Robert Kenny and Colin Talbot’s Applestealers (1974), for example. Could you discuss where you feel your early poetry practice was placed in relation to what was happening at the time? Did you feel that you connected, or wanted to connect, on aesthetic and/ or political terms, with one of the many poetry ‘schools’ or magazines that had by then appeared? Or did you feel that you were writing outside all that?

Ken: Well no one was called the Generation of ’68 then. And it seemed, really, to be a couple of tribes and individuals, nothing very unitary. In fact, like a leftist political party it consisted of warring factions, and what got finally ‘established’ was the conservative opposition. I wasn’t aware that the degree of activity then was unusual. If it was. Australian Poetry Now had dated very very quickly and didn’t have a very accurate take on what was happening: it merely cast a net. 12 Poets I didn’t know and am not sure I’ve heard of. Maybe I’ve forgotten. Applestealers did seem exciting.

Ken Bolton (left), Colin Mitchell, Glebe, 1976, photo Anna Couani

I was interested in the work of Laurie Duggan and John Forbes. They ‘had’ a magazine, called Surfers Paradise, but it was so casually irregular, and unambitious about becoming ‘the’ magazine, that you would only aspire to being in it for fun. Kris Hemensley’s The Ear in a Wheatfield was interesting and ambitious. It was very well informed and published poets you wouldn’t see otherwise anywhere else till years later. Aside from these, the poets I found interesting, I think, were John Tranter, Nigel Roberts, Jennifer Maiden, Robert Kenny and Walter Billeter, Rudi Krausmann — and my friends John Jenkins, Anna Couani, Denis Gallagher, Kerry Leves — and Pam Brown, whom I didn’t meet till a few years later.

In the mid 1970s I was mostly reading New York School poetry, and art history and art criticism in Studio International and Artforum, where the issues of the sixties were working themselves out — (abstract) Expressionism, Pop Art literalism, Minimalism, Conceptualism — or they were working themselves into an interesting grid-lock. My book Happy Accidents looks at this period: for me, ‘For Grace, After A Party’ and O’Hara’s Collected Poems, ‘Tricks for Danko’ by Robyn Ravlich, John Forbes’ ‘To the Bobbydazzlers’ and ‘Admonitions’, Laurie Duggan’s ‘Cheerio’, Kris Hemensley’s ‘Rocky Mountains and Tired Indians’, were some of the poems I remember being struck by. And Anna Couani’s prose, some French novels by Robbe-Grillet, Butor and Duras, and my day-dreaming about Robert Rauschenberg, Frank Stella, Pollock.

Anna Couani, Annandale, Sydney, circa 1980, photo by John Tranter

Not to mention Kenneth Koch’s ‘Fresh Air’ and ‘The Pleasures of Peace’ and Ted Berrigan’s The Sonnets and ‘Tambourine Life’, and Ashbery’s Three Poems. All this and more made up much of my mental world. Or these things are points that map out a mental topography — something like the map of Winnie the Pooh’s Hundred Acre Wood, named Ken’s Head in 1975. A map that was maybe not very real in relation to the rest of the world. There would have been more anomalous things in there, too, that I’ve forgotten — Ponge, say. But lists like these... I was going to say “What good are they?” On the other hand, I devoured them as a young writer.

¶ Pete: In the ‘Further reflections’ to his Applestealers introduction, Robert Kenny says ‘There is also a trend of isolation from city to city, with very little interaction, really, between Sydney, Melbourne and Adelaide writers of poetry.’ He was writing of the early 1970s. Do you think this is an accurate reflection on what was happening (or not happening) at the time? I suppose I’m keen here to discuss a very interesting period of formation and resistance in the evolution of Australian poetry communities, and what that process says about how we absorb(ed) those larger national and international trends in poetics. So, do you feel that poets living in different Australian cities were working out different leftover problems from the 1960s? And if so, how and why were they going about things so differently?

Ken: That comes partly from the young Robert Kenny’s wish to generalize confidently. I mean, the mail was working. If you’ve hardly been writing more than a few years why would anyone in another city know you? But, by the time you’re in your mid-twenties, you do begin to wonder who’s out there in the other cities. And there was a degree of truth in Kenny’s perception. As I remember it, the truism was that Melbourne was a bit more informed as to European writing — partly the accident of Walter Billeter’s presence and Kris Hemensley’s connections. We’re talking small communities here, where Walter, Kris and Robert stood for ‘Melbourne Writing’ — along with, say, John Scott and Alan Wearne, and Pi O and his scene. That is, three groupings — as well as those too old or too uncool to count.

This is to recall and caricature the thinking of the time. Admittedly, I wrote it, but Happy Accidents — one of the few poems to be inspired by the mission of bibliography — provides a map of who was reading what in the 1970s.

Sydney seemed to me to have a Balmain scene (which always seemed to be already ‘over’ — but, though they left Balmain, the grouping was an entity), Adamson’s New Poetry scene, the Newtown/ Sydney University John Forbes-and-Laurie Duggan faction, and the Glebe types like me and Anna Couani, and our friends Carol Novack and John Jenkins.

Sydney stuff seemed less European-influenced, more in thrall to ‘the American model’, but also ‘sophisticated’ and smart-arse. Melbourne seemed heavier, more earnest: Bataille and Charles Olson making for a doughier mix than Sydney’s tipple of Ashbery, O’Hara, Berrigan and, say, Duncan.

I was in contact a good deal with Melbourne writers, particularly the Hemensley/ Kenny axis. Forbes and Duggan were friends with Wearne and Scott. That’s another Melbourne/ Sydney nexus. Tranter, I think, was out of the country for quite a while — in touch with both sets, though identified with those latter four poets.

Robert Kenny’s essay would have been written pretty early in the piece and is meant partly as a disclaimer about the anthology’s Melbourne focus. Applestealers included Forbes and Tranter, Viidikas and Nigel Roberts, for example — but there had been mooted for a while a Sydney equivalent. I gather it had fallen through and Applestealers expanded — from a Melbourne focus — to take in at least these better known Sydney poets — and thereby almost become, but not quite be, ‘national’ in focus. That is, it had poets from Melbourne and Sydney.

¶ Pete: Most of the poets you describe above as ‘interesting’ were then based in Sydney. Many still are. How did the Sydney community begin to define itself aesthetically, and as poets making poems and magazines and books? What drew you to that group of people? Were they just fun to hang out with?

Ken: Well, my experience of it was that someone in a share-house I was living in said “Oh, you write poetry? I know a poet — you should meet her.” I did, and went to my first reading and met three or four others there. You picked up from other poets what they knew — of ‘who’s out there’ and where they stood etcetera — and gravitated, or didn’t, to particular venues or groupings or magazines. Mostly you read books and wrote, drank, smoked, looked out the window and changed the record occasionally. How it’s been for me.

I’m not sure how much people defined themselves as part of groups or tendencies. Maybe the Sydney ‘position’ was to not do so, or to disavow doing so. I think the Melbourne wing were less like this — and I was happy enough to think that way, too.

Though I found Laurie Duggan’s and John Forbes’s work to be really on the ball, I didn’t know either of them very well until near the end of the decade. Same goes for Pam Brown. I was intrigued by her work and wrote to the addresses her books gave, but she’d always moved on. I don’t think I met her till 1978 or 79. There’s an account of my first meeting with John and Laurie in Homage to John Forbes, where they came around (I felt) to tell me I’d arrived: I’d been published in The Ear. From the mid 70s I hung around with Anna Couani and also John Jenkins and Carol Novack. We were friends. Our writing and thinking had some commonality — different for each of us — but enough not to get in the way and often to be usefully provocative.

In Sydney, magazines and publishing imprints were mostly under-capitalized exercises in achieving fame. In Melbourne, they had more aesthetico-political purpose, as befits their more communitarian leaning. And maybe for that reason they often kicked on longer. I’m thinking of The Ear in a Wheatfield, etymspheres, 9-to-5, as compared to, say, Dodo, or Final Taxi Review or Leatherjacket or Free Poetry, which were all from Sydney and were more fugitive, irregular, and less programmatic. I ran a magazine myself, Magic Sam, and Anna Couani’s Sea Cruise Books was a press we began jointly back then.

New Poetry, the main Sydney magazine, was for the ‘Romantic’ strain. This was the chief divide in the Sydney scene, a division which set up (the absent) Tranter at one pole and Adamson at the other. The Melbourne crowd would also have seen themselves in opposition to the romanticism of New Poetry. Or bemused by it! (I think. This is a recollection of what was a subjective view anyway. Was the view correct? Is the recollection? The view was very partially informed and partisan.) A wider view would have noted the Poetry Australia-affiliated. Squaresville, so we ignored them.

So my writing of the mid 70s grew out of reading these people, thinking hard about it all — the ‘modern’, the international, the new art. There were the letters I was writing and receiving from Kris and Robert, the knock-out effect of particular poems (like the ones I’ve named), and bits of conversations from day to day. In 1973 I finished the degree I mentioned before, majoring in Art History, and I tutored for a year in twentieth-century art, took a year off and then tutored a little more.

1975 was about the first year I wrote any interesting poetry. I had money for a few years to do an MA, and I just lived on that and wrote and read. I was in a large share house (in Arcadia Road, Glebe) with a floating population that included Rae Desmond Jones, Kerry Leves, Vicki Viidikas and Denis Gallagher. Laurie Duggan moved in soon after I left, I think. I lived for a time with writer Anna Couani (moving just down Glebe Point Road, to Leichhardt Street) and began publishing a magazine at that time. My own first books came out in 1977 and 1978. My life began to change, various alliances, friendships, orientation and focus all began to change and shift.

Anna Couani, Annandale, Sydney, circa 1980, photo John Tranter

¶ Pete: I’m interested in your idea of the ‘usefully provocative’. For me, that phrase resonates with the ironic ‘beautiful impenetrable’ refrain scattered throughout your 1977 ‘Four Poems’. Your early work has a ‘usefully provocative’ take on questions of form and influence. What I mean is that rather than settling for singularly Romantic or Modern poetic influences, you seem to have taken a more ‘cinematographic’ approach — scanning a whole set of conceptual and plastic formations via constantly shifting depths of field. I keep seeing or hearing your first two or three books through the representational logic of 1960s French or Italian cinema rather than ‘Black Mountain’ or ‘New York School’ poetries, per se. The Citroens, the structuralism, the smoky free-form jazz... Your work then seems to have revelled in the provocative constructedness of ‘the beautiful’.

Ken: Well, Dorothy Green (in Nation Review) found it provocative. She practically wanted to call the police! But she was getting on, really. It was odd to have got her attention at all. She said it “broke all the rules” and that if people behaved in this way in other walks of life there’d really be trouble! She divined that I was a terrible person, too, from her, um, ‘close reading’.

But that first book mostly got good press — from Carl Harrison-Ford in the Herald and Robert Kenny in the Age. So, those on side were ready for it — and applauded its appearance. I was happy — but the general public didn’t notice one way or the other probably.

Cinema is in there — but largely as an easy genre-target to utilize and parody at the same time. (I had in mind things like Alain Delon’s Any Number Can Win, old movies like Rififi, etc.) I loved the way the crooks’ cars always seemed symbols of menace, inescapable doom-and-retribution, though I used them also to invoke, cornily, Death with a capital D and ‘time-running-out’, a deliciously over-determined teleology. (Is that the term, or eschatology?) The poem ‘Four Poems’ was published with three other poems as a book, Four Poems. The others are less cinematic: ‘Nonplussed’, ‘Water’ and ‘Terrific Days of Summer’. Green and the others were reviewing that.

I watched a lot of TV as a teenager, as well as reading a lot of books. Not a lot of ‘art-house’ cinema, mostly the old black and white Hollywood stuff that was aired repeatedly then. So I know the stars of an earlier generation better than my own.

The models were Rauschenberg, Jasper Johns, Larry Rivers, Jim Dine — and the more decorative, expressivist people (who mostly got put down as 2nd or 3rd generation in relation to Abstract Expressionism): Bluhm, Joan Snyder, Cy Twombly, Stella and Olitski and Louis — and our own Tony Tuckson and John Firth-Smith. So, that visual mix, plus Berrigan’s ‘Bean Spasms’ and ‘Tambourine Life’, and the O’Hara odes. And the idea of Coltrane and Miles (the Coltrane of Giant Steps and Ascension, the Miles of Miles Smiles, that’s what I was listening to, aside from Howling Wolf and that sort of thing). Maybe it wasn’t the ‘idea’ of Coltrane and Miles but the attempt to approach and be licensed by the physiological and aesthetic effect of their pacing and interludes, the disjunctions and overload Coltrane features and the recession to simplicity at the end. (I’m talking mostly of Coltrane.) I mean, I wasn’t especially sentimental about jazz — smokey clubs, cool record sleeve photographs — but those two or three particular records I played endlessly in the early and mid seventies. I had them under my skin. I wasn’t trying to be provocative in this so much as ‘terrific’. I wanted the poems to be ravishing — in part, at least, and in another part to be parodying that.

I’m not sure how you’re meaning “structuralism”. I had barely heard of it in the early 70s and found it very hard to get my head around in the late 70s when I first tried. Roland Barthes was more fun, and Foucault, whom I probably began reading around 1978. But Levi-Strauss I missed out on. The provocation I was interested in, now that I think about it, would have been that of my peers and imagined audience who might have believed in an authenticist ethic of ‘poetic voice’. You had to mean the words: it had to be ‘expression’ in that sense. My bower-bird sampling and presentation of loosely linked items would (to some of them) have been pretty infuriating. I’d have loved that effect. Vicki Viidikas, for example, saw it as unacceptable. The work didn’t seem to me to be daring — though I hoped it was exhilarating. And beautiful. And witty.

¶ Pete: So it wasn’t film then, behind it?

Ken: Not in a theorized way. Though, like anyone, I was familiar with filmic conventions. No, I thought of it as like collage. I imagined Rauschenberg worked in a similar way, that he had lots of familiar images, taken from magazines, some already on silk-screen stencils and ready to use, favourites he knew so well that when he was making a large composition an empty space that needed something would ‘suggest’ the perfect thing he was looking for to fill it, enliven it. I made those poems out of many half-written or failed other poems, cannibalized — and added new stuff as I put it together — words, phrases, passages. If the poem ‘stopped’ I opened up my old notebooks of first drafts and fragments and letters to people and notes — and chose something. Or looked for something: and you’d find something appropriate, that either fit with or contrasted with, or made an interesting departure from, where the poem was already, that contributed to the pace and rhythm.

I still write that way occasionally, but I didn’t want it to turn into a formula, or become too familiar as a process. And you need the material to build up, the pool of stuff you’re going to draw from.

¶ Pete: So you still do these things in your current writing?

Ken: Yeah. The ones you might have seen are... well, ‘August 6th’ in Untimely Meditations, which also exists with a few revisions as a Little Esther book, or ‘Blazing Shoes’. There’s another, ‘Europe’, that should come out in 2005.

¶ Pete: I have to say I love the errata slip in ‘Blonde & French’ (1978):

BLONDE & FRENCH —errata

p.10, l.7 should read

—the poem (-moving relentlessly

p.14, l.19 should read

feet that pound the sheets

p.33, l.3 should read

the air & things are all aroused &

everything, & that.

Ken: Touching, aren’t they, errata slips? I was very pleased with “the air & things are all aroused & / everything, & that”, so casually nominalist and also designed to bug those who quivered too much to the word “arouse” — though it’s ‘beautiful’, too. But it labels it beautiful. Cynical, huh?

¶ Pete: It gets better!

Ken: Yeah?

¶ Pete: Because the next bit goes:

it was like some sort of ‘stuff’

Ken: Yep, blinding exactitude. Dorothy Green, save us! Isn’t stupidity great? “It was like some sort of stuff.” I can imagine Boofhead saying it, or Dan Akroyd.

¶ Pete: In a way this little gem says a lot about the ‘expressivist’ sampling you mention, insofar as the poem acts, at least on the surface, as a primary moment for engaging context, via pastiche or motion or whatever. It’s almost ‘projectivist’, in the classical sense, ‘one perception must immediately and directly lead to a further perception’[4], but as total construction rather than pure result, as such. There’s a very ‘kinetic’ drive to your sense of ‘the physiological/ aesthetic effect of ... pacing and interludes and the disjunctions and overload and recession to simplicity.’ I know Kris Hemensley was the main Olsonist at that time, but perhaps the general drift of that kind of poetics was more pervasive?

Ken: About those poems’ Projectivism ... I don’t know. I’d read a good deal of Olson, the poems, the letters to Creeley and Cid Corman, the essays. But as technique it is pretty compatible with some of what the Beats were doing and the New York School. Projectivism was a consciously articulated rationale, that maybe the others (in 50s/ 60s US poetry) were getting by without — going on their nerve. Is Kenneth Koch a Projectivist? No — well I wasn’t either. Was Laurie Duggan?

Creeley’s parsimonious attention to line-breaks and breath, and his Puritan/ Protestant ethical diction, I found sort of pietistic. (All that fetishized hesitancy.) And Olson was so grandly bombastic. I’m being ungenerous here — but after an initial interest I didn’t go back to reading them much. Their themes weren’t for me — nor were Duncan’s or Levertov’s.

Nigel Roberts at the launch party for Issue # 3 of John Forbes’s magazine Surfers’ Paradise in the beer garden of the Courthouse Hotel, Newtown, Sydney, on 12 March 1983, photo by John Tranter.

I briefly liked Ed Dorn, and again in his later phase. And yes, Kris took the Olson ‘project’ seriously and derived impetus from it. Nigel Roberts always struck me as related to it, too, though most people link his name to San Francisco beatdom. His tone has that kind of strength despite the grace and lightness in there too.

¶ Pete: Actually it’s funny you should mention Ed Dorn. I kept being reminded of him when rereading Blonde & French, especially in the poem ‘kodak’ where you mention ‘gunslinger’ twice. Purely coincidental?

Ken: Yeah. I’ve still not read Gunslinger! I knew of it, and I’d probably read Hands Up! It was the North Atlantic Turbine book I knew first. And then I read him again from Hullo, La Jolla onwards, in the 80s. But no, I was simply referring to cowboy movies.

¶ Pete: Gunslinger is one of my all time favourite books. And Hands Up! I’m a bit of a Dorn freak. But to get back to it, on a more technical level I’d like to ask you about ‘process.’ In your interview with John Kinsella you say that

In the ‘70s it was called the poem “of process”: you wrote the poem’s unfolding, in its context ... For me the self-reflexiveness involved is for a kind of self-consciousness that is epistemological — a reminder of the basis for opinions — or of the purely subjective or circumstantial (even ‘determined’) nature of one’s ideas. It’s against certainties.[5]

One of the striking formal elements of Blonde & French, and indeed a lot of your work, is a very explicit attention to punctuation — the ‘scoring’ of the process, as it were. Your poems are replete with parentheses, colons, asterisks, quotations, commas forced to the beginning of a line from the preceding endline, etc, like:

‘minimal’ poem

marvelous & miraculous

as a tennis player, or the system

of organisation moving through

/ a poem,

— that was

(??)

— the poem ( — moving relentlessly

down the page like some

basically simple but seemingly

complex system of locks, or system

of movements/ from one court

to the next court ‘of appeal’

,legal points taken up

like a system using rhyme

,which says “each time...

Specific aesthetic decisions are being made at each point of punctuation, which is to say nothing new, but how does a contemporary reader reconcile an ideology of ‘openness’ or ‘process’, with what appears to be the considerable degree to which control is being affected by the scoring of the process? Is it for or against certainty? I am interested in your thoughts on this hinge between gestalt experiences and the subsequent organisation of contextual detail into the art object, the explicit formation of its visibility. Perhaps, contrary to your statement to Kinsella, there is absolute ‘certainty’ AS process, in the sense that your ‘scoring’ is made very visible.

Ken: Well I always thought I was overdoing it, but I just couldn’t stop myself. I trust people to read properly a little more now. Or maybe I don’t try anything so obtuse now, or I figure I’ve learned how to do it. I was learning on the job, of course. But, yeah, they’re heavily scored — my alternating doubt/ confidence/ ambivalence were very precisely scored. It was my uncertainty you were getting, exactly, not your own. Well, notionally.

¶ Pete: I didn’t mean to imply that there was anything obtuse or overdone — my question is a genuine one... I’d like to discuss more about the ‘scoring’ of a poem of process. The tension between ‘process’ and ‘construction’ seems important.

Ken: Well for a while everything I wrote was scored that way. Not just ‘the poem of process’. There were the slashes of Olson’s style, line breaks and intervals between words or phrases, white space on the page between one clump of words and another and the whole panoply of punctuation marks that could be used. For a while I employed too many. Or so I soon began to feel. I mean, they’re written now — and most of the effects, individually, work. But their number could exhaust a reader who was attending closely and wondering what weight to give each. I didn’t mean them to be experienced as a code: I wanted a reader to more or less ignore them but be affected by them — their reading slewed or slowed or inflected by these devices anyhow.

I still punctuate more than most and would like to do so less.

For me it’s to do with pacing and irony, even sarcasm, in the tone of the writing from one moment to the next. It is not strictly related to Process Poems. I didn’t write all that many of those at the time in any case. I’m using the term as I understood it then and still do — to indicate a writing that contains many references to the conditions of its composition, their ongoing nature, a poem which is affected by those conditions and attends to the effects. For me this meant a poem whose thinking was concerned to push ahead — via logical thought and association — but where the situation and duration of the thinking were recorded within the poem. This would tend to make the poem diaristic, self-conscious, responsive — a tracing and mapping. Now, depending upon what kind of focus you were pulling or maintaining, this might mean attention to the minutiae of seconds as they ticked by or whole afternoons and days as they slipped past, fidelity to successions of temporally isolated thoughts and feelings, or a more or less continuous monitoring of unbroken sequences, including — in both cases — distractions, repetitions, mistakes, asides and more.

Process poem in this sense I didn’t do such a lot of. It entails a relatively long poem. The only one I remember as fitting the bill was called ‘Serial Treatise’ and was published in Magic Sam #5. It was unfinished in any case. But those habits I incorporated into a lot of my poems. They’re there still. The thing I was drawn to was that thinking should come with its context and provisionality evident and attached. Cards on the table. I was interested in a poetry that could think and employ the language of thought, but not the bullying certainty of discursive prose, nor the bardic insistence of ‘poetic’ language with its intimation of heightened perception, stronger and finer feeling. Pam Brown referred to ‘Serial Treatise’ as a meditation — on poetry as neurosis, as hobby, as process, as joke. In the 80s I wrote another longy that is diaristic at least, and maybe to a degree it would come under the rubric of ‘process’. The EAF published it: Two Poems–A Drawing of the Sky. The design on the page is pretty straightforward. Schuyler’s ‘The Day Of The Poem’ was the initial ‘model’ for it.

The long pieces in Four Poems were collaged and assembled. There are probably bits of process poem in there, but that’s not basically what those poems are. The term ‘presentational’, not that I like using it, pinpoints one of the things about their ‘being’ and composition that distinguishes them from the process poem’s fidelity to something outside itself. Even so, you decide what tone or tonal range is the point and your exclusions determine — or are part of the determining of — the particular process poem’s formal presence. They are two different impulses. In one case I want poetry to do some of the work of philosophy, or at least of thought. In the other I just (‘just’) want them to be aesthetically terrific — organized abstractly or musically, so as to be abstract and musical. I forget whose ‘line’ it was (Clement Greenberg’s or Michael Fried’s, I think) — that the decorative could be heroic. I took them to mean the huge veils of Morris Louis, the all-over fields of energy and line of Jackson Pollock. But the literalism of Jasper Johns’s beer cans and maps and flags — of pictures like Good Time Charlie — had to be in there too. For me. That is, I wanted excitement but, as well, intelligence’s cool. Anyhow that’s what I saw in Berrigan’s ‘Tambourine Life’, O’Hara’s ‘Oranges’ or ‘Meditations in an Emergency’. It’s what I saw in my notebooks, looked at in the right way — a kind of suggestive Rosetta Stone.

I guess you’d ‘score’ a poem of process around criteria of shifting mood and tone and the registering of time, pace and interval. The presentational poems are also scored around pace and interval — and around the isolation, or relative enjambment, of the (collaged) ‘material’ — the many beautiful or funny, quiet or loud ‘bits’, and the bridging bits of new writing that linked them or riffed upon them. They allow much more indeterminacy than the other, more propositional poems. The voice is more mobile and disembodied.

Does this relate to your writing, to Empty Texas?

¶

Pete: Yes, very much, especially the collaging of ‘voice’ and various other cultural materials.’ Although in Empty Texas I was also interested in working through relationships between process and genre.[6] I still am, in different ways. I keep writing across a range of genres, and in a way my engagement with each of them, and the practice of writing across them, draws a great deal on that ‘poetics of process’ you discuss. Although, my head often plays a hybrid Projective/ Black Mountain riff, while remaining keen to work out how anything might be useful in an Australian context, whatever that is. I’m very interested in a poetics of presence.

Which brings me to another thing I thought about when rereading Blonde & French. It’s almost a truism nowadays that Modernism didn’t really cohere all that well in Australia. John Tranter, for example, takes this view in a number of his accounts of how things arrived here. So, I’m interested in discussing how you see your work’s place in the development of an Australian postmodernism... to my mind Blonde & French is now one of our classic ‘postmodern’ poetry books. Do you think there is such a thing as postmodernism in Australia? What does it look like? How do you feel your early poetry worked to establish a postmodern context here?

Ken: Modernism is a term applying to a century or more: 1860s to whenever, 1960s maybe. Postmodern suggests a similarly epochal sense: a period supplanting the Modern. I guess Modern can be taken to be larger than modernist — starting either with the Renaissance or the Enlightenment and resulting, maybe, in modernism. Modernism as a growth and revision of Romanticism and Symbolism?

But making the postmodern programmatic, an ism? ... I mean an ism based on the failure of a previous one? Maybe. I guess there was a bit of that ‘dancing on the grave’, mocking the supposed verities and axioms of a kind of modernism. But these were old jokes by the 70s — repeatable, but only of value because some people insisted on still being shocked by them.

¶ Pete: Thank God Dorothy Green was out there?

Ken: Exactly. My sense of it in the seventies was just that these were the next steps, a continuation of modernism, moving beyond Greenbergian formalism and the New Criticism, but continuing, I thought, modernism’s self-critical spirit. I hadn’t heard of Postmodernism till I saw an article by David Antin (in Boundary 2). I could see what he was saying, but I never thought the term would get off the ground. This was some time in 1977 or 78 I think — and probably the term was up and running already in a number of discourses.

Periods don’t usually get to name themselves — not large periods. I guess specific ‘styles’ and ‘movements’ do: Post-impressionism, Minimalism et al. Postmodern might be one of those — a 1980s/ 1990s ‘style’? But the 21st century might seem very different if anyone is bothering to look back in three hundred years time, from some library in the Himalayas.

I know you don’t want that kind of focus. You might mean the specifically all-that-was-old-is-new, parodic and discursive and ironic style of the late 70s and early 80s — literary equivalents of Imants Tillers and Juan Davila, or Jenny Watson or Linda Marrinon. Terrific artists.

Then there are the more broadly historical/ economic usages of the terms — where modernism and the modern end with multinationals and the close of the Cold War, the weakening of nation states, the ‘end of history’ stuff. Not much to do with styles of four or five years’ duration.

There’s a problem, anyway, in talking about a specifically Australian postmodernism. We’re broadcasting much more weakly on the English language band than the US and the UK.

¶ Pete: They’d be like Channel Ten and the ABC, respectively.

Ken: Yeah, and Australia is community radio. We have a regional listenership, most of whom — like most of us producing the stuff — also listen (mostly) to those major discourses. I think Australians produce good work. But Australia is not sufficiently a world to itself for the tides it generates to create self-sufficient movements.

You know Terry Smith’s essay ‘The Provincialism Problem’?[7] It’s an oldie, but it gets reprinted and referenced regularly because, though depressing, it states that problem pretty fairly, I think. The new comes from abroad, from metropolitan centres. Local innovation, in this view, will normally be imported. But, whether or not it is, still, the next style, the style that replaces it, will not be a development of the local, but the next importation. There is no local continuity, influence doesn’t happen. Nolan and that crowd came about during the isolation of WWII. That isolation ended.

¶ Pete: We’d quarantined the Surrealist exhibition.

Ken: Yeah. Then abstract art arrived from New York. Nothing to do with Sam Atyeo. Now Tony Tuckson produced world class stuff derived from that vein, and arrived at it himself. Sure, but the world didn’t need it. Only us. We’re pleased for him. It is the same with evolution: you need an isolated, small gene-pool for variation to have a significant effect.

This is all very broad brush.

We had begun to think the centres might be losing power, that in the agora, with more voices being heard, ours might be too. (And individual voices are.) That was the 1990s/ 1980s view, or hope. Now it looks like the shift is shaping to be so much bigger, as though climate change, population shifts, etc., are going to make a lot of that irrelevant. Maybe I’m feeling a bit of “the early 21st Century millenarian anxiety that swept much of the West” — to quote that 23rd Century Himalayan History Of The Culture Of The Old West, where, surprise, surprise, I’m footnoted!

I think there are Australian postmodernists. I don’t know at all whether there is an ‘Australian postmodernism’. Is there a New Zealand one? Does anyone care?

It’s nice that you think Blonde & French is a classic of postmodernism here. I don’t think it was much read. It never sold out its edition. The Penguin Selected did finally sell. (Out of print, at last!) But my next biggy had hilarious sales figures in its first year. Double figures, I think. Low double figures, but way out of the teens. Let me assure you.

I was all for internationalism when I began, but a very unexamined notion of it. Weirdly, now I see my stuff as strictly for the local market. I’ve absorbed and used a lot of influences — just to be grown up, fully qualified — but my poems are pretty much focused here, where they’re not wanted. Maybe I’m not part of the culture.

Hey, remember when Howard did the deal for a trade agreement with the US? When asked why he’d ceded away our rights to protect cultural production (broadcast stuff: TV and film industry, I think), he answered, Well, you can’t have everything. Maybe you can’t have anything. Maybe Holt saw it coming.

¶ Pete: Maybe Holt heard the toll of Five Bells.[8] In fact, if we think about this in a specifically Australian context, Australian postmodernism is contextually reacting to Australian ‘modernism’ (or is it the pre-postmodern?) as much as it absorbs the kinds of internationalism you mention above.

Ken: I hope you’re right.

¶ Pete: We’ve spoken a lot about your American influences in poetry, art and music, but how were you and your mates writing in a strategic way against the cultural weight of what had happened in Australian poetry? I’m thinking of, say, Slessor and Hope and Wright, even good ol’ Malley, for example. Is part of the provincialism problem — the double-whammy of having to deal with inadequate provincial histories as well as the hyper-identification with what’s going on ‘over there’?

Ken: History of inadequacy, you might say. But maybe an inadequate history. I wasn’t impressed with the elders. But I hadn’t read them properly. Slessor’s three or four best poems I’ve since come to like a lot. I hadn’t read them then, not even ‘Five Bells’. Wright and Hope seemed dull to me and do still. Not unintelligent, but old-fashioned. Laurie Duggan and John Forbes, John Tranter and Jennifer Maiden, Ken Taylor and Bruce Beaver, seemed to be in the same world that I occupied. The older stuff, and the contemporary conservative stuff, to me, was one with boring poetry from the US and UK mainstream.

But I, personally, was not identifying a ‘project’ of Australian poetry that was failing or needed to be opposed. Most others had a better idea of Australian literary history than me, maybe a ‘motivating’ understanding. Wrongly, I wouldn’t have understood it if they had. Murray and the Canberra faction, for example, seemed alive and well — and pretty terrible, I thought. Worth reacting against. But even “alive and well” they didn’t seem like ‘history’.

(I love that phrase, You’re history, pal.)

I just wanted to write poetry that was able to think about and somehow deal with the world around me. The poetry I disliked seemed committed to misunderstanding the problem — proud to be out of date, pleased to be going down with the ship, advertising all this by an adherence to general terms of reference — and kinds of diction — that were out of the past. Always preferring to feel rather than think, to proffer the helmets and robes of myth rather than Baudelaire’s ‘modern’ business suit. (You know that line? It’s one of my favourites: “the heroism of modern day life”.) I extended the latter, of course, to mean jeans.

I used to read Laurie, John and the others — to see this view corroborated. Those three or four poets might almost have been enough — but in fact they put me on to a huge armory of other examples, other attempts along the same lines. I mean the New York School chiefly. A warehouse of the great. If you were pushing the science analogy, well then, here was a vast documentation of other experiments and data. Naturally you’d take advantage of it.

But we weren’t wearing lab coats and it was art. John Jenkins and Anna Couani and I were working pretty seriously at it, brains focused on our various ideas of ‘what was the point’ — unaware, maybe, of exactly how similar or different our ideas were from each other’s. This, despite all the flagons and joints... and hours that just disappeared. Similarly the poets in Balmain and Newtown! To say nothing of Annandale.

Kuhn’s ideas of ‘paradigm shift’ and ‘loci of commitment’ were attractive to me back then. I still think that way.

¶ Pete: I’ve seen old copies of Magic Sam, wine stained and smoky... I’d like to ask you about the magazine culture of that time. You’ve mentioned the names of a few already, but tell me about how you personally got involved with creating poetry magazines, like Magic Sam. I think that got off the ground before Blonde & French came out?

Ken: It did. I saw how it was done by watching Rae Desmond Jones pump out Your Friendly Fascist. I loved that magazine: most of it was so deliberately terrible and the ‘aesthetic’ was very punk. Mostly Rae scratched the artwork onto stencils with a safety pin: hilariously inept drawings of pigs wearing cowboy guns and police hats and nazi insignia. Anyway, I’d seen how to use a gestetner. And there were other interesting magazines coming out that way. Kris Hemensley’s Ear In A Wheatfield was the main one.

Rae Desmond Jones, photo by John Tranter

Anyway, I wasn’t likely to get published in the established magazines in a hurry — New Poetry, Southerly, Meanjin — and didn’t like them in any case. I wanted my stuff to appear beside work I liked: you know — poems that shared enough of the same aesthetic would be mutually reinforcing. That was the idea. The desired aesthetic was “work that was aesthetically self-conscious” — or something like that. By which I meant ‘epistemologically self-aware’. Which also sounds like something I said back then. I probably had to publish a lot of stuff that was neither here nor there in that regard — but that was what I dreamed of, a poetry not devoted to high-toned and poetic language and not tied to highly metaphorical or ‘trope-based’ thinking. Anyway, there were good people in it. Which issue were you looking at?

¶ Pete: I haven’t got one myself — I saw a copy at a friend’s place one evening. Can you say a little more about the production of Magic Sam? Was it a collaborative effort? Involving various artforms, reviews, etc.? Who were the ‘epistemologically self-aware’ you published?

Ken: The production I mostly did myself: typed stencils, did the mimeograph printing and collated. Anna Couani has some editorial input into some issues, soliciting some of the material. Anna provided some terrific drawings to issue two, I remember. There was also a fair bit of silkscreening that I did — of the covers and for sort of novelty pages. There were even hand-coloured pages. I loved doing it. Distribution was the problem. The first two issues sold well. Then I broke a prospective ‘double issue’ into two separate issues (numbers 3 and 4) and issued them together with more or less the same cover. Not a smart move. Number five sold out — I think because the cover was very good. Number six I did while living down the south coast and it had taken too long. Time to pull the plug. As an adjunct we had begun Sea Cruise books — Anna Couani and I. The first three were me, Forbes and Denis Gallagher. A year later Anna chose Kerry Leves, Robert Kenny and Kris Hemensley. When Anna and I parted ways she continued the Sea Cruise line.

Laurie Duggan does the dishes, Coalcliff, 1981, photo Micky Allan

As to ‘epistemologically self-aware’, I suppose the obvious candidates would be Anna Couani, Laurie Duggan, Pam Brown, Kris Hemensley and Robert Kenny, Noel Sheridan’s piece ‘Everyone Should Get Stones’, David Miller (UK), Denis Gallagher, Allen Fisher (UK), Robert Lax (USA/ Greece), Bernie O’Regan, Colin Symes, Sal Brereton, John Tranter, Phil Jenkins (UK), John Jenkins, John Forbes, Michael Brownstein (USA), Rudi Krausmann. We published Steve Kelen, Alan Jefferies, Gig Ryan, Phil Hammial. Luke Davies and others, but I’ve probably covered most of the central names. My piece in number five was excruciatingly epistemologically self-aware, as I recall. I did a lot of filler artwork under pseudonyms — A.F.Drawings, Raoul du Plicit, Neville Selley, Drunk Persons. ‘Neville Selley’ did a lot of the reviews, too, billed as ‘Far-Out Sam — carnivore of the terrific’ — along with people like Laurie Duggan, David Miller, John Jenkins. Artists like Micky Allan and Kurt Brereton contributed work. I’ve forgotten the dates, but I think maybe issue two was out around the same time as my Blonde & French book, or not long before. The last issue was #6, some time in 1980. Number one was 1975 or 76. They were A-4 size and a hundred or so pages: poetry, prose, interviews, art, some criticism.

¶ Pete: Why did you move south, from Sydney to Coalcliff? What was the story behind that? How did it affect your writing, and your sense of writing from just outside of the metropolis?

Ken: I moved in 1980, I think. I was living with Sal Brereton, who thought getting out of town would be good. We found a place in Coalcliff, just past Stanwell Park, a derelict house to squat in. From day to day it was isolated — but beautiful in a quite intensely affecting way: escarpment looming right behind us, so that the sun set about 2pm during winter, and fabulous sea viewed through trees and vines in the other direction. Our house was perched on the cliff, between mountain and sea. The main road ran right by about 4 metres from the door, so we had coal trucks roaring past every now and again, and endlessly long coal-trains clanking slowly by. But mostly it was pretty silent. The beach was right near by.

Ken Bolton, with Sal Brereton, Coalcliff Beach, 1981, photo Kurt Brereton

We didn’t see people every day, but most weekends we had visitors and people often came to stay for longish periods. I’d have been more isolated (and lot less happy) in Hornsby. I took my dole form to Wollongong and brought groceries back, and went to Sydney for fun every month or so. We saw a lot of Pam Brown and Laurie Duggan, Denis Gallagher, Kurt Brereton, Kate Richards. People moved down there, too. Rae Jones was already in the area and Alan Jefferies and Erica Callan arrived.

I don’t think it affected my writing. I had come to a kind of end with the way I was writing then and in response produced Notes For Poems and ‘Blazing Shoes’. These felt like changes at the time — Notes did, anyway. But I was in a bit of a lull. Sal’s writing was probably the main new influence. I taught a little at the Wollongong Art School, which was part of the Technical College back then. Late in 1981 I got a residency at the Experimental Art Foundation in Adelaide and six months after that finished they rang offering a job — and I went. And I started writing again. Adelaide felt a lot more cut off. It still does.

¶ Pete: Your rejection of ‘the metropolitan literary centre’, in this case Sydney, seems heralded in some respects by your poem Christ’s entry into Brussels or Ode to the Three Stooges. This long poem was written and published before your move to Coalcliff, but it gets inside a deepening tension around your sense of how a local poetics reacts to the burgeoning weight of European and American models. The Marvell epigraph, ‘For Death thou art a Mower too’, is a pretty exact descriptor for the great un-namable’s work on suburban domestic pastures. And the poem itself is quite a sharp and funny commentary on the power of American cultural icons, the global ‘stooge’ affect, over local capacities. Were these issues behind the lull you speak of? How did they affect your writing practice?

Ken: The poem was written without much thought beyond trying to start at a high energy level and keep it up all the way. I think it runs hard for a page or two and then slips down a gear to a more formulaic procedure: a role-call of films with the Stooges’ Mo replacing the actual actors. Which is still funny: “This guy is Dada” and “Am I ‘Mo’?” coming from Kim Novak I still find amusing. But the logic is quicker at the poem’s beginning, the syntax more surprising.

You’re right, the poem’s mood is a little dark. Whitlam got thrown out while I was writing ‘Terrific Days’, hence the slightly tremulous, desperate tone of much of that poem. I still remember walking down Glebe Point Road when a VW bug went by with a loudspeaker crying “The government’s been sacked! The government’s been sacked!”.[9]

Maybe by this time it was clear Fraser was in to stay. I know poems can be taken to mean more than their authors meant — but at that stage I was not consciously talking about ‘the weight of the West’. And the move from Sydney, which came later, wasn’t a rejection of anything. Sal thought a space of time in the country would be good! I wrote the Stooge poem in Glebe and was living in Redfern, I think, when Tom Thompson published it. It sold out in about a month!

The Marvell quote came last. It needed something used cynically right at the start, to signal its mood and tone. And the poem recycles some imagery of a Victor lawn-mower ad that had been used earlier in ‘Terrific Days’. Putting Marvell at the beginning meant the poem would have an inane/ portentous note when the mowing word was echoed further down the line.

The trough I fell into — had been in, really — was that I didn’t know how to top the poems in Four Poems. And I didn’t want to repeat them (because I had nothing in the tank, for one thing — you know, material to use). And I didn’t want them to become a formula. And I suppose I thought I’d better see what I had to say — while at the same time not conceiving of poems in that way, as editorial or message. (And I’d have felt I didn’t have much to say, in fact.) It was time to change tack.

¶ Pete: Tell me about the early days at the Experimental Art Foundation, and how they drew you to Adelaide. What was the job?

Ken: Pam Brown was working at the EAF in 1980/ 81 and persuaded them to give me a residency there over December 1981. I stayed on quite a while through January and February, editing and printing some books by Pam Brown, Laurie Duggan, Sal Brereton and Denis Gallagher, and giving readings and seminars. Anyway they liked me enough to phone around mid 1982 to see if I wanted the offset-printer’s job there and I said “Yes”. I turned out not to be a great printer — being untrained and having a second-hand and difficult machine to use, so I quit after a year or so, but managed to hang on to work there of one kind or another. It was still a small organization with a director and one or two part-time staff. It had been formed to promote conceptual and post-object art in the mid 70s — and that impetus had left the artworld by this time, so the EAF was headed for a period of adaptation — which it managed with a series of directors who kept it afloat and managed to up its energy levels. It was located in the basement of an old building and moved to a series of abandoned factories till it found its present task-designed premises. I recall interesting shows (Juan Davila) and tediously null efforts that I think I won’t name — back in the early and mid 80s.

Ken Bolton and Mary Christie in the kitchen at Westbury Street, Adelaide, 1984, photo Michael Zerman

¶ Pete: You then published three books in fairly quick succession, Talking To You (Melbourne, 1983), Blazing Shoes (Adelaide, 1984) and Notes For Poems (Adelaide, 1984). Talking To You has strong traces of Sydney still — Glebe, Redfern, the Forest Lodge Hotel and beers with Forbes, Tranter and Pam Brown, among others. How did the change of city first affect your poetry?

Ken: Those books came out in quick succession, but Notes For Poems was written soon after I got to Coalcliff and Blazing Shoes before I left there for Adelaide. Talking To You was a collection of work written since Blonde and French. But finished before I moved to Adelaide. In principle it could have included the other two. (It does sample Notes for Poems.) The title poem, ‘Talking To You’, registers the impasse I sensed at the time — and Notes For Poems was one response to it: the adoption of a manifestly artificial, high, diction and the ‘permissions’ that came with that. ‘Notes’, too, states the impasse — and in fact it is an introduction... to something big, that never arrives: you get just a high-handed sketch of what you, um, might expect. It’s a ruse, of course. The poem satirizes merrily enough, being windy and rhapsodic, prostrate and profligate, swoony and bitter, and attacks various people. Appropriately it was praised for being beautiful on the one hand and, on another, called innocuous by a reviewer who didn’t want to let on exactly who had been satirized and how. Dorothy Green, Les Murray, Bob Adamson. (‘No one must ever know!’)

So, although I was in Adelaide when they came out, they weren’t Adelaide poems. The Adelaide literary scene didn’t find me very amusing — nor I it.

¶ Pete: How different was the Adelaide scene? Or should I first ask was there one?

Ken: It seemed to me that there was Friendly Street, a monthly open reading in a council-community centre, which was pretty uninspiring. There was probably a ‘scene’ around people like John Bray and Peter Goldsworthy and Noel Purdon and Peter Ward. I read at Friendly Street when I arrived. The ‘Stooge’ poem drew no laughs and no one spoke to me. They were trying to tell me something. I hope I didn’t read it wrong.

On the other hand I lucked into a very supportive group of people, a kind of ‘in’ scene centered around the visual arts, music, alcohol, and more or less libertarian-leftist ideas and attitudes (and education, politics, design even). I wrote within that context — and to some degree to that context — in exile from the literary world I conceived of as Newtown, Fitzroy and maybe St Marks Place occasionally. Pam had moved back to Sydney, Laurie was in Melbourne, and Berrigan was dead a year before I found out!

Talking To You got a review down here written by three people! You don’t often see a poetry review with three signatures under it. Written by two very elderly poets and a young but hilariously conservative art critic. It was a “waste of paper”, they thought, in-the-hard-economic-climate-of 1982. It was the locals telling me to keep off their turf — and get no ideas above my station. Stern reproof! But I was having a good time finding out about a new city, with a more varied group than I’d mixed with in Sydney and being, from day to day, involved with the visual arts.

Friendly Street has drifted further towards inanition but it’s still going, courtesy of the Writers Centre. More recently Adelaide University’s creative writing course, initiated by Tom Shapcott, has energised writing down here over the last few years: there is a growing body of young or new novelists created by it. But novelists don’t need scenes — just a publisher — and locally that’s Wakefield Press.

The writers I know to hang around with at all are very few — Cath Kenneally and Linda Marie Walker — whose idea of their ‘context’ probably resembles mine, I think.

¶ Pete: Did you find that the first few years helped you to focus your poetry writing in particular or new directions? What did you start producing then?

Ken: I was living in a share house that was a very social one. People were mostly working, going out a lot, there were lots of parties, lots of talk, and children in the house, too. I was also involved with a lot of people at the EAF, especially after I quit as printer and started running their bookshop and writing art criticism. Previously I’d been living with just one other person and both times they’d been writers. And the previous shared house, in the early seventies, was almost all poets. People were living in their heads a lot, slightly isolated and preoccupied — and young — and unemployed. I now had lots going on around me. And I was cut off from the East Coast literary world, not getting published a lot, and no grants. So these are the factors.

As well, since about 1979 or 1980, I’d been very taken by James Schuyler’s later work, from The Morning Of The Poem volume. Once I’d realised how great he was — I mean the specific ways in which he was great — I suppose I was able to re-read much of his earlier work and see it there, too. I think that was the literary influence at the time.

This combination of factors might have meant that my poetry was more involved with everyday life than it had been before. Maybe? Maybe there just was more life in my days now. And aesthetics and politics were there to be thought about because of the household I was living in — but also through the art world: there were others working at these things too, all around me. And, being isolated, and having made a decisive change in my own circumstances, I probably became a lot more conscious that this was going to be the shape of my ‘career’ from now on.

I think I was drifting before. Not that I was very energetically pursuing my chances down here, either. But a little more than before. And I had to have an attitude (or a range of them) to my situation as a poet, and to the situation of ‘the’ poet. The result, very briefly, might be that I continued the manner of the poem ‘Talking To You’, but with more grist for the mill, and more discursively. The pair of poems that makes up Two Poems — A Drawing of the Sky is one outcome.

A good deal of my 80s work never got published, either in magazines or in book form. It was a long while between books. In the late 80s Penguin and Angus & Robertson were both interested. A&R, though, while their editor wanted the book, had a Reader with the right of veto — and this reader regarded me as anathema (in the full, theological sense). A&R were afraid to cross him: he was the big seller in their poetry list. He threatened to move, I gather. He’d occasionally featured as a figure of fun in my poetry, so there was a degree of self-interest in this veto. Or so it seemed. But, really, who can tell? So instead of two books I got one, a Selected with Penguin. Handy, but a little odd. I mean, the world didn’t know me enough to be interested in a Selected Poems.

In the mid to late 80s — I think about 86 or 87, maybe earlier — John Jenkins and I began collaborating. And I began a new magazine, Otis Rush, and started organising regular readings. Otis made me feel more connected with the scene nationally. The readings for a while established me here, as a presence.

¶ Peter: So what were you up to as a writer?

Ken: I think my regular pattern is to push a main manner — poems that seem to have a speaking or thinking voice or presence — and to vary from that, for relief or reinvention, or out of frustration with its familiarity (or the familiarity of my own devices to me), by reverting to something obviously ‘artificial’: the collaborations, poems like ‘August 6th’ or ‘Europe’ that are quasi collagist, letter poems that make the address more crucial, sestinas, or even, lately, occasional attempts to write with rhyme schemes, just for the difficulty of it. The title poem of Untimely Meditations represents a lot of that: the place of poetry is one of its preoccupations. It’s informed by thinking about the visual arts and Australian art history. It’s got a loopy manner of address, being supposedly a lecture. It’s discursive. And so on. (By this time I was beginning to write in reaction to Australian literary contexts.)

Ken Bolton (left) and John Jenkins, Melbourne, late 80s

¶ Pete: I’m really interested in your collaborative work with John Jenkins. We’ve talked about collage and process — collaboration also stands out as one of your defining activities as a poet. How did you and John start working together, and what at first motivated you?

Ken: I guess it looks defining because John and I have done a lot of it — and most poets don’t do it much. I don’t see it as defining, though it might or must say something about me. It says something about me and John, who’s the other half of the collaboration. It seems to me that we do it because we can. We’re very old friends. I met him in the mid 70s when he came from Melbourne to live in Sydney. We hung around together on an almost daily basis for about three years. We didn’t start working together that way though until the middle 80s when he came down to Adelaide for a week or so.

Basically, once you’ve caught up on gossip, what else is there to do? We tried it and it was fun and, almost from the first, successful: we liked the results! Every now and then some poet or other in my past — in everybody’s past, I think — had suggested a collaborative, round-robin poem. And I’d shudder. It was invariably an exercise in dreadful, prankish, surrealist humorousness. Relentless, too. And terribly literary. (A mix of writers and non-writers works best... for exquisite-corpsing.) I haven’t liked or understood my contemporaries’ attempts at collaboration much. They often seem built on competitiveness, an insistence on being tellingly ‘characteristic’ (their signature styles evident), and a kind of one-upmanship — a higher ground is always sought — of canny caveat and obscure reservation. Yech. John and I want to have fun.

Photo: John Jenkins (left) and Ken Bolton. Photo by Mark Thompson (Institute of Backyard Studies).

But they’re interesting, I think, because they foreground models of poetry. They’re parodic. They’re ‘pretend’ poems. Maybe all poems are, I know — either pretending to be poems (on the dubious basis of resembling poems) or, more testingly, they’re experiments that posit, or pretend, that “this can be a poem”, this can be counted as a poem — despite its not resembling the known so closely.

Would that we were all that avant-garde. I’m not sure we are. We are very good friends, though, and the poems are mostly a function of that. We’re not out to impress each other. I’ve said some very stupid things in front of John. There’s a tape of us working up The Gutman Variations — poems in the manner of the Sidney Greenstreet character in The Maltese Falcon — and at one point I ask John, “Are there any mountains in Africa?”

Of course, I’m forgetting there’s another kind of collaboration, that usually produces chains of poems, or a poem of chains of responses, where the writers are not concerned in the way we are but are interested in pushing some more serious thought, usually expressly as dialogue. We’ve not done that much.

¶ Pete: Could you say something about the process?

Ken: You mean, How do we do it — or What’s going on?

¶ Pete: Do I have to choose? Both!

Ken: People are always curious as to the mechanics. But I think they are pretty much as you might expect. ‘What’s going on’ is that the poems tend to set up a kind of poem — a tone, a tactic, a conventional or recognizable manner and pattern of associations, ideas, development — and undermine it or wrench it in another direction, or they somehow take it dubiously ‘out on a limb’. Nearly always there are two impulses warring in the poem, or else egging each other on, not usually evident as two voices. The central poems in The Wallah Group, say, have an amusingly unstable speaker, sometimes sentimentally hysterical and weepy, then resigned and realist, at other times stoical then furious. Other poems, like ‘Sandwich Hand’, are ludicrous, yep, but only in the way old-fashioned, soliloquy love poems always are. In other respects, having set the sights for a declaration of love, we give it our best shot. It’s a nuttily moving little poem, I think, though it’s a love poem from someone who might be a serial killer. But probably it didn’t set out ‘aimed’ like that — there’s little pre-poem discussion. The nutter-love poem becomes a possibility with the second-person pronoun in the second stanza, is put aside for nearly three more stanzas, then becomes a decisive twist: affection mixed with self-solicitude — “I-love-you, O-sole-mio” sort of thing.

John Jenkins, Cath Kenneally, Melbourne, mid 90s

The poems’ self-consciousness, their foregrounding of definitions or types of poetry, are grounds for considering them both conservative and exploratory. The paradigms they knock over — or, at least, stress — are quite available and reified. On the other hand, they do test them amusingly. They’re not quite straw men, but they’re mostly easy targets. Often what’s tested, or even given a re-launch, in ridiculous garb, is not a form so much as an ethos — the humanism, for example, of the poem whose point of view is that of a minor god responsible for “Trieste, Arezzo, Pisa, Adelaide, Leipzig and other smaller cities.” Maybe, often, we avail ourselves of dud or handicapped forms to see what we can make them do under cover of comedy. Regularly, John and I are, happily, at cross-purposes while writing them — though we’re in agreement about them when they’re done.

¶ Pete: How does this stuff sit within your other, independent work?

Ken: I don’t know. For me it’s had a liberating effect. I don’t know about John. It frees you to play with genres and modes you never would. John has always had access to that fanciful area as a writer — but formally collaboration has probably been good for him. I don’t know. We never talk about the poems in a theoretical way, except to say Good one! or to agree that something didn’t work.

¶ Pete: John Jenkins lives in Melbourne. You’re in Adelaide. How do the poems get written?

Ken: We’ve worked both in Melbourne & Adelaide at different times. A few have been done through the mail, but mostly the incentive is the amusement of working together. We laugh a lot as we do them, and have some amazing conversations too, in parallel, so to speak. Usually — say 50 or 60% of the time — one of us holds the pen and writes and the other expostulates, attempts to generate either phrases or a whole poem.That is, one transcribes, maybe doing a little editing in the process and also adding stuff of his own.

¶ Pete: Is this done by hand, holding the pen, or do you generally use a typewriter or computer to work together?

Ken: No, handwriting. Anyway, next up, the person taking dictation may, or may not give regular feedback to the speaker. At the least he would most usually re-read what had gone down ‘from the speaker’s mouth’. He may come clean as to what he’s combined with that material, near the end, so they can wrap it up ‘together’ — or he may just decide that it’s going well and attempt to present something as a fait accompli when it seems done. Sometimes the ‘speaker’ will insist, I want this one verbatim, in which case it’s all kept ‘above board’. Often the poem proceeds with the ‘speaker’ in the dark, till some certain stage when — say the scriptor [where did I get that word?] — decides there are some choices to be made, or which he has already made, that the other now needs to be apprised of because they’re decisive. Then the poem might resume, as before, with the speaker ‘brought up to date’ but once more progressing ‘blind’ from that point. In these situations the ol’ scriptor might have been leaving a great deal out. Or not. Adding a good deal — or not.

Ken Bolton, John Jenkins, Melbourne, early 90s

The next most usual method is that the scriptor takes dictation and speaks his own interpolations, and the editing, out loud as he goes. There’s discussion and disagreement, of course, as we go. And misgiving and approval, give and take, special-pleading, bargains are struck. Less often, and mostly for a change, we will both be writing and will hand stuff to the other to add a bit — exchange pieces of paper — so we’ve got two or more poems on the go at once. This always makes me feel about seventeen and as though I’ve been kept in with my best friend after school and we’re rapidly completing some stupid assignment together. You never get to laugh or talk as much this way: it feels like work.

Usually these writing bouts are intensive periods of a week or so. You need a change of routine.

¶ Pete: You need to get out and walk around occasionally, have something to eat...

Ken: Exactly. Snacks and walking. You can see that from an academic point of view these ways of writing might present a challenge to so-called classical conceptions of the author position and notions of intentionality. I don’t know who last actually held these classical points of view.

¶ Pete: Well, it wasn’t me! I wonder if poets feel they are both ‘Speaker’ and ‘Scriptor’ when working on their own as well.

Ken: I don’t usually feel as though I’m taking dictation, writing my own stuff. And I hate feeling that I’m impersonating ‘myself’, or artfully conspiring to create effects of authenticity. Usually the poem’s over, suddenly withered — and gets scrapped — or changes tack quickly to incorporate that realization and escape it. John and I are either writing ‘impersonally’ or we’re doing comedy. Or both. The comedic stuff is the more philosophical, I think. But I can imagine John’s caveats about much of this, and qualifications. They’d be right, too.

With things like the verse novel, The Ferrara Poems, there’s a bit of planning necessary. We wrote the first part (‘In Ferrara’) as a parody of the most stilted opening for a novel that we could imagine — where the characters are simply ‘introduced’, one after the other. The ‘event’ that finally ends it as a kind of introductory chapter was simply the introduction of an ‘unexpected’ character, ‘by accident’, so speak. Then we thought, “Let’s do another chapter”. We figured these two poems would live, quite separate from each other, as poems in a collection, and that it would be fun for the reader to meet the characters again, later on in the book of poems. So, a second chapter, called “We meet again” is what we did. These two were in our first collection, Airborne Dogs, and reappeared in the Philip Mead, John Tranter edited Penguin/ Bloodaxe Book of Modern Australian Poetry.[10] This chapter would have to have ‘action’, so we figured the most anodyne thing would be to send them on a picnic. Deadpan was the joke and that it be inanely ‘footling’. A while later we decided that, while we liked the idea of the collection including those poems, it would be fun to ‘accept the challenge’ and actually complete the novel.

I remember we did a lot of walking around Adelaide for this, discussing what we might do and working out some rules. Then we sketched out a kind of plot plan. There should be triangles of people — couples would be too stable: they should be challenged by a third, destabilised. There must be an action, a mystery that could be ‘resolved’. We invented one that would be buried — noted, but forgotten by the reader, so that its formal resolution would be just that, a resolution, yet not feel like it had ended any logical tension. The character’s various crises should all get solved — but never by any action of their own. Each new character would enter the story by falling over (off a bike, down a mezzanine, etc). And so on.

John and I have a very easy relationship. That’s probably the key.

¶ Pete: Does the combination make for a third, other writer? Can the different contributions be told apart?

Ken: I don’t think it makes for a third and different writer. But it tends to make for product that we might not, individually, have produced and in some cases which neither of us could easily have produced: because we have different mind-sets and patterns of emotional and aesthetic response. There are poems where we can identify who wrote which bit. But sometimes we both think we wrote the same best bits and other times we don’t know who wrote some lines. People who know us well haven’t been as able to unravel the works as surely as I’d have thought. In half a dozen cases poems are almost solo efforts, but they are licensed and inspired by the collaborative thrill. Usually these are partly ‘in the manner’ of the other and are a bit like gifts to them.

John Jenkins, Ken Bolton, Melbourne, mid 90s

I’m sure The Circus, which should be published some time in 2005 or 2006, might not have got going if I hadn’t had the experience of writing with John. I’d have toyed with the idea and dismissed it. (In fact I could easily have written it with him.) John’s recent verse novella, A Break In The Weather, is the sort of thing he might always have imagined, I think (see his poem ‘The High Tides’) — but he’ll have attempted it maybe with more confidence after our work together.

We haven’t worked together for a few years now. So we’re ready for more, I imagine. We’ve got one more small volume to appear some time in 2005, Poems Of Relative Unlikelihood. And that will mean most of our stuff to date is published.

¶ Pete: So if your and John’s collaborations were collected up into an, ah, ‘Collected’, and you had to write your own blurb, what would it be?

Ken: We’ve written lots of blurbs for previous volumes: The bio-note in The Wallah Group answers your question about our methods:

As to composition: sometimes the mail is used, but for the most part the poems were composed... via a mix of procedures: talking at cross purposes, insidious undermining, go-you-one-betterism, you-do-the-ideas-I’ll-do-the-afterthought-and-description, or, I’ll say the things you say — you say the things I’d say — even, Look-this-thing-needs-finishing — and sundry other methods.

The Nutters Without Fetters blurb is more expansive: the authors, it says

are both mad. Even so they have managed to publish a lot of books. And all of these books have been terrific. Which goes to prove that, whatever they say against him, in this respect Freud was right — Art and Madness, they’re connected.

Rather bright, isn’t it? It goes on to mention a novel and a verse novella: