Bill Luckin and Barry WoodPoet as Expatriate:Jack Beeching, 1922–2001

This piece is 5,000 words or about ten printed pages long. |

|

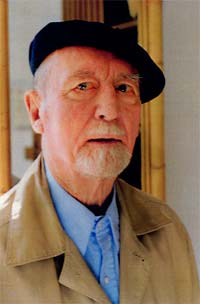

Jack Beeching, the expatriate writer who died at the age of seventy nine in Palma de Mallorca in December 2001, was born in Hastings. He attended the local grammar school. His father had inherited land and then dabbled in business. But Beeching chose a different path. Before he was twenty one, he had published his first co-authored collection of poems, shared with a school friend, Fred Ball. In 1939 university beckoned. But war intervened and Beeching’s life was transformed. He served in the Royal Navy and the Fleet Air Arm. His ship was torpedoed and he was seriously wounded. Twenty years later this would play a crucial role in his decision to spend the rest of his life in the Mediterranean south. |

| |

|

|

In the 1940s and 1950s Beeching developed his skills as poet, writer and reviewer. He became a board member and regular contributor to the high-profile left-wing periodical, Our Time. He got to know John Davenport, Jack Lindsay, Randall Swingler, Edgell Rickwood and, from a rather different neck of the literary woods, Hugh Kingsmill and George Barker. (Who, one sometimes wondered, hadn’t he known ?) He wrote for Arena, hustled and bustled in Fitzrovia, and worked in advertising, public relations and publishing. (He also taught briefly and tried his hand as a smallholder.) Beeching was appointed editorial adviser to Lawrence and Wishart and encouraged Nancy Cunard to edit Poèmes à La France (1947), a collaboration that presaged a life-long commitment to anti-Fascism. He was a natural linguist. His Spanish and French were excellent, Italian serviceable. Beeching also knew Catalan, Portuguese and German and taught himself some Greek and Turkish. Latin was read for pleasure. |

IIBy the mid-1950s Beeching had begun to write fiction. In 1959 he published Let Me See Your Face which drew heavily on personal experience of what was still then considered to be the risqué world of advertising. This was followed in 1968 by a thriller, The Dakota Project: the predictive and successful Death of a Terrorist in 1981: and in 1988 Tides of Fortune, a block-busting saga of life in Roman Britain. (There are two other completed, unpublished manuscripts, The End of England which traces a twentieth century British family’s experience of total war, and Roscoe.) During the early years as an expatriate Beeching reviewed widely and in the late 1960s wrote a Paris-based arts and cultural column for the Times Educational Supplement. |

| |

|

|

Beeching had always been attracted to, indeed obsessed by history. To help make ends meet during the Fitzrovia years, he had written pseudonymous longue durée surveys and what would now be called ‘topic’ books for use in secondary schools. As an exile, he engaged with the classic literature of exploration and discovery. He contributed an introduction to Alexander Olivier Exquemelin’s The Buccaneers of America (1969): edited, abridged and introduced Richard Hakluyt’s classic Voyages and Discoveries (1972): and then wrote three impressive studies in political, social and cultural history. The first of these, The Chinese Opium Wars (1975) is a scholarly and readable book. The second, An Open Path: Christian Missionaries 1515 — 1914 (1979) develops themes implicit in the China volume. Beeching’s final large-scale historical study — The Galleys of Lepanto — was published in 1982 to high critical acclaim, with the Times Literary Supplement describing it as essential reading for all those wishing to understand the making of early modern Europe and the final decline of the Ottoman empire. Each of these studies is underwritten by a preoccupation with the ironies and tragedies of imperialism, conflict between weak and strong, travel and exoticism, and the role of the individual in shaping or redirecting political and social change. |

| |

|

|

Beeching identifies two central conversionary tasks which underpinned the historical missionary enterprise. Firstly, indigenous populations must be convinced that every individual possesses a unique and individual soul. Secondly, there must be widespread acceptance that ‘any relationship based on sexual pleasure which degraded the less willing partner to the status of an object was inhuman.’ Beeching claims that Catholic and Protestant initiatives failed in all those places in which it proved impossible to inculcate the ideal of the monogamous family ideal. Sometimes the methods that were deployed to achieve that objective took on a ‘grotesque form’ — for example, in Tahiti, nakedness was forcibly covered with a ‘yard and a half of textile’. |

III

Jack Beeching was an autodidact who became a considerable poet, novelist and historian. Impressive ranks of Oxford Classical Texts and the collected works of Milton, Donne, Browning and Keats in flats in Spain, Greece, Turkey, France or wherever comprised a personal academy in exile. He knew many poems by heart. He cared deeply about Greek and Latin history and mythology and possessed a comprehensive knowledge of the prose, poetry and prosody of the eighteenth century. Hardly surprisingly, he was also an authority on the archaeology of modernism. An omnivorous reader, Beeching had a jackdaw mind which served him well when he delved into archival material.

|

| |

|

|

As we have already seen, Jack Beeching’s schematic but ironic view of the world was rooted in a detestation of totalitarianism. He disliked random use of the word ‘fascist’ but, once convinced that a genuine example of the species had been identified, words rapidly gave way to action. Happily ensconced with a bottle of wine in a sleepy mountain village on the Franco-Italian border in the late 1980s, Beeching was approached by a bespectacled campaigner for Le Pen’s National Front. The elderly poet chased the young man, belabouring him round the shoulders with a walking stick. Then he walked slowly back down the street and resumed a discussion about the relative merits of rival translations of the French imagists. |

| |

|

|

Towards the end of the Menton period he discovered, or, rather, was himself rediscovered by a musician-daughter who belonged to none of the ‘official’ Beeching families. This gave him enormous pleasure. When physical strength finally declined, he made a new set of friends at the Palma dialysis centre and drew on the experience to lavish praise on the Spanish welfare state and — inevitably — mount a scathing attack on the ailing NHS. Poor old England! |

|

|

|

Jacket 27 — October 2004

Contents page |