Robert Adamson

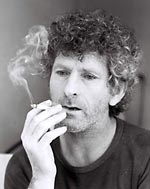

Robert Creeley, 1926–2005

Robert Creeley

Robert Creeley’s reach across time and space was generous, and he touched lives from one side of the planet to the other. Here one of Australia’s leading poets reflects on a meeting with Creeley in Sydney in 1976, and the intense literary and personal friendship that developed. This piece was first published in the Sydney Morning Herald on 16 April 2005. It is 3,000 words or about 7 printed pages long. You can read Robert Creeley’s author notes page here, which has direct links to seven pieces by Creeley in Jacket magazine.

You can read Robert Adamson’s 2001 poem ‘Letter to Robert Creeley’ at the end of this file.

Robert Creeley, who has died at 78 from pneumonia and complications from lung disease in Odessa, Texas, was one of the major American poets of the 20th century. He was a teacher, a scholar, and a fierce presence: "I look to words, and nothing else, for my own redemption either as a man or poet."

Just days before he died, he gave his final reading — in Charlottesville, Virginia — breathing from what he called "portable wee canisters of oxygen about the size of champagne bottles". In between the poems Creeley said very simple things that rang true: "There has been so much war and pain during the last century. We need to learn how to be kind; kindness is what makes us human."

Creeley lived in Providence, Rhode Island, and was a distinguished professor of English at Brown University. The director of Brown’s arts program, Peter Gale Nelson, said of him: "Rare enough to be a great poet, even rarer to be a great person, as Robert was. He was a vibrant presence."

Previously, Creeley had been a professor at Buffalo University, New York State, for more than 20 years. Charles Bernstein, a poet and former Buffalo colleague, commented that "Creeley’s place in American poetry is enormous."

"You can’t help but love a world in which a Robert Creeley happens," wrote the poet Tom Pickard, a friend of his in Britain.

Creeley had a strong influence on Australian poetry. He visited Sydney in 1976 and many remember his readings and lectures, along with his passionate and articulate performance. He wrote 60 books, of which The Collected Poems of Robert Creeley 194–1975 (University of California Press) and his recent book, Life & Death (New Directions, 1998), are widely available here. (New Directions published his last book, If I Were Writing This, in 2003, but it is not widely available around the world.)

Creeley turned around many students heading for self-destruction in one form or another. He changed my life when he came to Sydney by pointing out that my Australian accent was infinitely more right than the language of my poetry at the time — heavily influenced by another American poet, Robert Duncan. After he left Sydney I wrote one of my most popular books, Where I Come From. It was as easy as speaking because Creeley had given me permission to be myself in my writing.

Robert White Creeley was born in Arlington, Massachusetts. He lost the sight in one eye in a car accident when he was two years old. His father, a prominent local doctor, died of pneumonia a couple of years later. After this setback his mother had to go back to full-time work as a nurse. They moved to a farm outside town and times were hard.

The loss of his eye and his father affected Creeley profoundly. For the first half of his life he travelled as an outsider, his heavy drinking often leading to brawls with friends and strangers. Creeley was sometimes an angry young man who wanted "the world to narrow to a match flare".

He was accepted into Harvard University in 1943 but when his lecturers made it impossible for him to study Hart Crane and Walt Whitman he began attending jazz clubs where he listened to Charlie Parker and Thelonius Monk. He read Ezra Pound and Coleridge, along with the English Jacobean lyricists who were to influence his poetry. The poet Delmore Schwartz, one of his teachers, introduced him to the 17th-century poet Henry Vaughan, who became an abiding influence.

The young Creeley found university uninspiring, and as his love of jazz grew his grades fell, until he finally decided to leave altogether. Unable to sign up for World War II because of his sight problem, he joined the American Field Service and drove ambulances in India and Burma.

He returned home with two medals, and although he was accepted back into Harvard he dropped out before graduation in 1947. He married his first wife, Ann McKinnon, and moved to a farm in New Hampshire where he bred Birmingham Roller pigeons and attempted to establish a poetry magazine. He wrote to the poets Pound, Charles Olson, William Carlos Williams and Louis Zukofsky and asked them to contribute work. They all sent contributions but the magazine didn’t get off the ground.

However, the poets he wrote to became friends and life-long influences, especially Olson, with whom Creeley conducted one of the great correspondences in modern poetry. Olson introduced him to fellow poets Duncan and Denise Levertov, who became lifelong friends. Creeley lived in France, Spain, Finland and Guatemala for periods, then settled for several years in New Mexico.

He enrolled at Black Mountain College in North Carolina at the invitation of Olson, the school’s rector, and while earning his bachelor of arts he edited Black Mountain Review, the college’s literary magazine which published not only the Black Mountain poets but Beat writers such as Allen Ginsberg.

Black Mountain, established in 1933 as an independent, co-educational, four-year college, was America’s first experimental college. Featuring democratic self-rule, extensive work in the creative arts and interdisciplinary academic study, its staff and students included the painter Josef Albers, composer John Cage - who staged the first multimedia "happening" there in 1952 — and the architect Buckminster Fuller who built his first geodesic dome there in 1948. Its board of directors included Albert Einstein and Carlos Williams.

The first person to coin the term postmodern, Olson was formulating his famous theory of projectivist verse during this time. Its tenets spread around the world and by the 1960s had reached Australia. Many of the poets in Sydney’s Generation of ’68, including myself, were influenced by the Olson-Creeley essays on poetics.

In retrospect, the theory of projective verse is rather vague in parts. The main thrust was against the dominance of the Anglo-American tradition of poetic forms. For Creeley, the thing was to create a new aesthetic where poetry could operate in an open field; "form is never more than an expression of content and content never more than an expression of form," he said.

When Creeley spoke at Sydney University in 1976, he downplayed the role of projective verse in his work. He spoke of the importance of jazz and painting as inspirational fields.

Creeley spent several years at Black Mountain along with artists such as Franz Kline and Robert Rauschenberg, choreographer Merce Cunningham, and Duncan. There he learned to teach, and he honed his craft as a poet until it became swift, intricate and vigilant. His timing of each phrase, every line was exquisite.

By 1953 the experimental college was falling apart, its funds were cut and Olson was struggling against the tide. It closed in 1956 and the last issue of the Review was published in 1957.

Creeley made trips to New York City, where he frequented the Cedar Bar, the famous meeting place of the abstract expressionist painters. He often spoke with Willem de Kooning, who could demolish the whole Black Mountain mystique with a casual comment: "The only trouble with Black Mountain is that if you go there, they want to give it to you."

Creeley went to the West Coast, where the San Francisco poetry renaissance was in full swing. He met Ginsberg and Jack Kerouac, who had their first books out. Creeley was still waiting for a reply from New Directions. Kerouac wrote that everyone had the highest regard for "Caro Roberto, the secret magician". However, he had no more tricks, and about this time his first marriage broke up. He moved to Taos, where he met his second wife, Bobbie Louise Hawkins, secured a position at the University of New Mexico and wrote a novel.

The tide turned again in 1958, when Scribner published Creeley’s short stories The Gold Diggers and Other Stories and his novel The Island. After the success of these two books, Scribner went on to publish his collected poems, For Love: Poems 1950-1960. These books were also published in London.

Much later Creeley wrote: "D.H. Lawrence was the hero of these years, Hart Crane — they were the people who kept saying that something is possible ...Writing is the same as music. It’s in how you phrase it, how you hold back the note, bend it, shape it, then release it. And what you don’t play is as important as what you do say."

In that last sentence, Creeley is echoing the great French symbolist poet Mallarme. I’d been studying Mallarme for a decade and had just published my book Swamp Riddles, which was influenced by him.

When I met Creeley in 1976, my first question was "What do you think of Mallarme?" He quoted a line: "Is the abyss white on a slack tide." The next instant we hugged and began speaking, simultaneously, and continued without pause until he went on his way. He spoke like lightning, his words flashed and hit home, then resounded in our heads for days.

Creeley had come to Sydney from New Zealand to lecture and read his poetry in the Seymour Centre and at Sydney University’s English department. Michael Wilding was able to raise his fare via the Literature Board because there was a conference, the American Bicentennial Seminar. It was a last-minute tour and, considering the publicity, a tiny advertisement in the paper, it’s a wonder anyone came. But his reading and lecture were packed out.

He was staying at the Hilton and we took him back there after the reading. I drove my Mustang back to Lane Cove and as we walked through the door, the phone rang: "Come and get me, it’s a bleak scene here at the Hilton." We were still singing and drinking Jim Beam at 3am when we dropped in to see a friend of mine, Gayle Austin, who had a midnight-to-dawn radio program on the ABC in the early days of Double J.

Creeley read poems and spoke about music. Phone calls came in from all over Sydney, the listeners loved him, his poems were breaking hearts on the air. We tried to get his session recorded, but there was no sound engineer and nothing happened. When dawn came I took him fishing. We went spinning for tailor under the Harbour Bridge. "Bob, there’s our Opera House," I said, and he replied: "I didn’t come half-way around the world to go sightseeing."

It was about the best time in my life. Over lunch I told Creeley I couldn’t understand the fuss some of the poets in Australia made of the New York poet, Ted Berrigan. He sat me down and read Berrigan’s long poem Tambourine Life. It washed over me in a great wave of music and weird images revealing a sharp satiric wit. I understood that the American spoken word was a different thing altogether from the way we spoke in Australia. I learned more about American poetry in the time Creeley was reading than I had in 15 years from books. Then he flirted outrageously with my first wife, Cheryl, and by the time he took off in a plane — heading for New Zealand and his wife-to-be Penelope — we were both in love with him. In the Mustang with the wind in our hair, we played Jimmy Buffet and Bob Dylan full blast. Sipping whiskey, tears streaking down our cheeks, we couldn’t tell whether they were from laughing or from the sadness of departure.

In 1988 Creeley was admitted to the American Academy and Institute of Arts and Letters, and went on to receive the Robert Frost Medal. In 1989-90 he was New York State poet laureate, under governor Mario Cuomo, then in 1999 he won the prestigious Bollingen Prize in American poetry, a Lannan Lifetime Achievement Award, a Guggenheim Fellowship, and two Fulbright fellowships.

"Reading his poems, we experience the gnash of arriving through feeling at thought and word," the poet and translator Forrest Gander wrote in a review of Life & Death.

On the day Creeley died, Penelope and two of his eight children were at his side.

Robert Adamson

Letter to Robert Creeley

I’ve heard the system’s closing down. It’s good

reading in books, old friend, your words about

what a friend is, if you have one. These

days I often think of Zukofsky

just throwing in the word

‘objectivist’ and how it works

as well as any label could. These

days we’re just words away

from death and I think

I’ve finally learnt to listen (your love

songs seem wise now that the years

have steadied my head) as you turn hurt

without sentiment to gain. I thought

of your clear humour when my father

was dying of cancer. I asked about the pain

and he spun me a line: ‘it feels like a big

mud crab having a go at my spine.’

This poem was published in Robert Adamson, Mulberry Leaves: New & Selected Poems 1970–2001, Paper Bark Press 2001 AU32.95 327pp 1-876749-48-2, 2001. You can read Douglas Barbour’s review of this book in Jacket 23.

Robert Adamson, 1985, photo by John Tranter

Robert Adamson had been a friend of Robert Creeley’s since they met in Sydney in 1976. In the last ten years they had exchanged over a hundred letters and emails. Creeley was associate editor for Boxkite, the literary magazine Adamson founded with James Taylor in 1997.

it is made available here without charge for personal use only, and it may not be

stored, displayed, published, reproduced, or used for any other purpose

This material is copyright © Robert Adamson and Jacket magazine 2004

The Internet address of this page is

http://jacketmagazine.com/26/adam-creeley.html