| |

Back to Rexroth Feature Contents List Kenneth Rexroth Feature:Kevin Gallagher

Introduction:

|

|

This piece is 1,000 words or about three printed pages long.

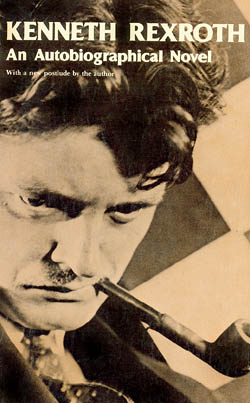

Now that his Complete Poems are laid out for all of us to see, we have no choice but to make room for Kenneth Rexroth in the canon. This special Jacket tribute celebrates the work of this great poet, essayist, translator and activist from the United States. |

Contrary to the popular label thrust on him, Kenneth Rexroth was a late modern poet, one of the early post-modern poets, and toward the end of his life (which ended in 1982) became an eastern classicist. Regardless of the form his poetry took, it always involved at least one of three themes: love, the natural world, or politics. |

Kiss me with your mouth

We with Rexroth, provide this tribute. .......... The night is full

Either through his own poetry or his relentless campaigns on behalf of younger poets, Rexroth influenced a wide array of our best living poets. Among them are Jerome Rothenberg, Robert Haas, Carolyn Forche, Philip Levine, and Gary Snyder. |

Yet, Rexroth was also known to be quite cantankerous and at times pretentious. By the time of his death he had alienated many who had seen him as a mentor. Eliot Weinberger’s “At the Death of Kenneth Rexroth,” reprinted here, reveals how his death had all but been a blip to mainstream United States media. In the Hungarian night

Although this “complete” work is over 750 pages, it really amounts to less than half of his poetry. Rexroth is perhaps most known for his translations of the Chinese, Japanese, Spanish, French, Greek and other poets. Indeed, his translations of the Chinese and Japanese are among the best selling books of poetry of their time and continue to sell well to this day. Fires

However, when he learned that he was up for a translation prize for these poems he admitted that he had written them himself. In this tribute, two former students of Rexroth, the novelist Lise Haines and the poet Christopher Sawyer-Laucanno share insight of the Rexroth who wrote the Marichiko poems. — Kevin Gallagher |

|

Kevin Gallagher is a poet and political economist living in Gloucester, MA. His poems appeared in Jacket 21, and review of William Corbett’s All Prose appeared in Jacket 16. |

|

August 2003 | Jacket 23

Contents page |