Meredith QuartermainLyric Capability: the Syntax of Robin BlaserA review of Miriam Nichols, ed., Even on Sunday: Essays, Readings, and Archival Materials on the Poetry and Poetics of Robin Blaser |

I don’t know anything about God but what the human record tells |

|

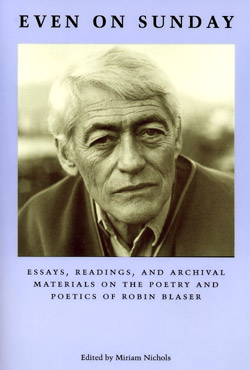

Thus opens ‘Even on Sunday,’ Blaser’s poem written for the gay games in Vancouver 1990, whose title has become the title of the first collection of critical work to focus solely on his poetry and poetics. Edited by Miriam Nichols, Even On Sunday: Essays, Readings, And Archival Materials On The Poetry And Poetics Of Robin Blaser is a long overdue beginning to a critical exploration of Blaser’s multi-layered and visionary writings.

|

|

The book begins with Blaser’s poem ‘Great Companion: Dante Alighiere I,’ which is highly appropriate, since Blaser’s vision of the poetic voice originates with Dante. The poet’s task, Blaser says, is the task of hell:

Inferno — facing Dante’s theology — even out of a Roman Catholic |

|

And hell is the problem of western paradigms for truth. ‘Churches,/ States, even Atheisms are given to personifications of/ totality,’ argues Blaser, but they are merely ‘exchanging bed linens.’

The archival materials usefully open the field of Blaser’s poetics and give this collection a wonderful range and variety. These include Blaser and Spicer’s animated postcard correspondence ‘Dialogue of Eastern and Western Poetry,’ annotated by Robert Duncan and edited and introduced by Kevin Killian; Nichols’ comprehensive 1999 interview of Blaser; photographs of Blaser from childhood on up; and long excerpts (in print for the first time) from Blaser’s 1974 lectures (‘Astonishments’) on Dante and on Joyce. ‘Dante Was My Best Fuck,’ Blaser laughingly says is the title of the Dante lecture. The talks were informal in the sense that they were given to a small group of people (Warren Tallman, Daphne Marlatt, Angela Bowering, Martina Kuharic, and Dwight Gardiner) but they were prepared, like all of Blaser’s work, with extensive scholarship. And they reveal a far-ranging poetic vision and philosophical investigation established early in Blaser’s career.

The ‘human element is no longer a visibility in the world at all,’ Blaser says in the talk on Dante, ‘but a closure of relationships, interrelationships, a lyric voice that speaks only of itself and closes into itself, no longer narrates the world and the actual astonishment of the world.’ Calling for recognition of poetic knowledge in public life, and of public life in our poetry — the intelligence in which we imagine ourselves — Blaser laments ‘the unrecognized disaster of a world devoured into human form, rather than a world disclosed in which we are images of an action, visibilities of an action, an action which otherwise is invisible, larger, older, and other than ourselves.’ And if Blaser’s language here is elusive, that is because the visionary and lyrical task he has set for himself is enormous and cannot be reduced to so many simple propositions. It is the task of a life-time’s work steeped in philosophers of politics, aesthetics and epistemology, unfolding in the serial poem The Holy Forest, which takes its name from the forests where the poet wanders in the Divine Comedy.

For Blaser, the ‘unrecognized disaster’ is the ‘blasphemy’ committed when human institutions substitute limited certainties for the totality of the possible — the totality of the forest. This is what Dante’s hell shows us — a theme Blaser sounds again in The Last Supper, his libretto composed for Sir Harrison Birtwistle’s acclaimed opera. In answer to this disaster, Blaser seeks not only to revive the public world but also to re-enact the lyric as a staging of public voices seen through the lens of a ‘singularity’ of body, soul, and intellect. ‘[K]nowledge (logos) is an activity, a revelation of content, requiring the specific, the particular, the place’ he says in ‘Particles’ his 1967 essay on poetry and politics. ‘The worst violence,’ he comments in the 1999 interview, ‘is an abstraction of abstraction, over and over again.’ As a refusal to abstract, the lyric voice is crucial to democracy and crucial to life. For it is not God, but man, who is dead, Blaser argues (suggesting this was Nietzsche’s conclusion also).

‘The Knowledge of the Poet,’ Blaser’s talk on Joyce, shows much of interest on the genesis of Spicer’s and Blaser’s poetics, their roots in some of Joyce’s early works, and their reading of Finnegans Wake, and much as well on the public world and the nature of poetic form. On Joyce’s puns and language play in the Wake, Blaser comments ‘There is no escape from the business that death is inside the language . . . . And as a consequence of the death of the modern world, the death of God and so on, all has to be worked in terms of the sensitization to language, the consciousness of language. This is why contemporary poetry talks about itself all the time.’ The talk suggests that for Spicer and Blaser, both love (not as mere sensation or desire) and ‘methodology of thought’ are key to the activity of poetry. And although language may be the seat of death, it is also the source of the ‘other than the world’ — the other that is not explanation. The ‘fall out of . . . realms of assurance and explanation and ultimateness,’ Blaser argues, has always been central to great art.

In the 230 pages devoted to essays and readings, Nichols seeks, like her subject, to cross boundaries between two turfs traditionally heavily guarded and walled: the realm of poetic knowledge, and the realm of academic criticism. Her grouping of ‘critical essays’ and ‘readings’ together and intermingled leaves open the question of where academic scholarship ends and lyrical knowledge begins, suggesting, and helping to create, useful cross-fertilization. This is highly appropriate, considering Blaser’s project is the ‘recovery of the public world’ through both scholarly philosophical investigation and the voice of lyric singularity — where the poet works in a

density and binding of thought, a re-tied heart that is only the other face of the untied heart. It may be full of blasphemy and praise simultaneously, as if they were the same condition . . . . To begin a life is to think. The feeling is held in the medium as a suddenness, image, a movement, and gathering out of the imageless. The form is the vital movement of image out of the imageless. Language is itself a first movement of form, a binding rhythmos or form of the mind.

Well versed in contemporary philosophy and the Olson-Duncan-Spicer-Blaser school of writing, Nichols is ideally positioned to open the way to a better understanding of Blaser’s work. Her ‘Introduction: Reading Robin Blaser’ details the history of Blaser’s publications and their reception, then sets out his connections to Whitehead, Merleau-Ponty, Lacan, and Arendt. She shows compellingly how Blaser’s project not only challenges absolute rationalism, but how it does so in a way parallel to and complementary to the challenge presented by such major thinkers as Derrida. ‘The vocabulary of his poems and essays frequently evokes the poetic and theoretical trends that have come along during the course of his writing life,’ she argues, ‘but it also suggests an errancy in relation to those trends . . . . [T]he reader looking for evidence of this or that philosophical system will find instead a rhetoric that bends philosophy toward poetic performance and Blaser’s own reading of modernity.’ In addition to perceptive scholarship, Nichols provides capable and sensitive editing, which carefully maintains in transcriptions of the taped lectures and interview the rhythms of speech and conversation and their fragile but important connection to thought.

One of the most delightful essays in the collection — full of wit and word-play — is George Bowering’s ‘Robin Blaser at Lake Paradox.’ Taking on Olson’s famous statement to Blaser ‘I’d trust you/ anywhere with image, but/ you’ve got no syntax’ (Blaser, Holy 184), Bowering embarks on a sinuous exploration of Blaser’s syntax in ‘lake of souls (reading notes’ (from the Syntax collection), an exploration which simultaneously interrogates the syntax of criticism. Pointing to parataxis as key to Blaser’s poetics and politics, Bowering writes, ‘Syntax means the way things are gathered, tactics for getting language together. Words, specifically, listen among fellows. A grammar of something is a set of principles showing the way it works. The rules, a strict grandma might say, a program for letters. But syntax: I guess that as synthesis is to thesis, so syntax is to tactics.’

Readers who have difficulty with Blaser’s syntax, says Bowering, are not stumped because of ‘zigging of the sentences but [rather] the learned referentiality’ in the poems. And Bowering is scathing about

Canadian literature critics who like the untroubled sentences and straight-ahead similes they can purchase in the lyrics of autobiographical Canadian poets. They want to find out about an individual’s exemplary pain at the loss of a father to cancer, or the ways in which killer whales and the rest of nature can be compared to human beings, to the shame of the latter.

Blaser’s project, Bowering concludes, is paradise itself, as it is found in fragments all around us — as it is found in a ‘gyre of quoted texts’ — a poetry that is not designed to praise the transcendent, but rather to enact the sacred.

‘That’s the drawer of poetry, closed to keep the lake/ from flooding,’ begins Fred Wah’s #114 from Music at the Heart of Thinking. Wah’s poem responds to Dante’s ‘lake of the heart’ — ‘the pool at the centre of the forest,’ which is one of the keys to Blaser’s poetics. (‘I want to move from the simple geography, the limited geography of my own place and my own time,’ Blaser says in the Dante talk, ‘I then fall into history — into time on a completely different level so that my present flows backward towards origins, primary thought, and begins to join the major movement of . . . poetic thought in the twentieth century.’) Nichols has included #110 to #119 of Wah’s serial poem which follows, like Blaser and Spicer, what Wah calls the ‘practice of negative capability and estrangement [learned from] playing jazz trumpet.’ ‘[I]t is probably the secret of syntax/itself, Wah continues,

Indefinite junktures of the hyphenated -eme-

In Norma Cole’s notes on ‘The Fire’ and ‘The Moth Poem,’ we find again the practice of negative capability — both of these writers echoing Blaser’s own practice, comparable to Susan Howe’s antinomianist voicings in The Birth-mark essays. While carefully considering Arendt, Agamben, Merleau-Ponty and others, Cole’s piece refuses to claim mastery; instead, it offers fields of sense and the possibility of emergence.

In addition to these readings from scholarly poets, Nichols has included five, more conventionally academic papers by David Sullivan, Andrew Mossin, Scott Pound, Paul Kelley, and Peter Middleton. Three of these offer various ways into the Image-Nations poems. In his thorough examination of Blaser’s philosophy of the public and the real, Andrew Mossin writes ‘I take him to mean that only through a genuinely dialogic poetic practice, one not seeking the self-affirming closures of a transcendent or idealized subjectivity, can poetry begin to suggest the repleteness and incommensurability of worldly experience.’ After considering the push-pull relationship between ‘I’ and ‘you’ (a mode of apostrophe) and contrasting them to the work of Emily Dickinson, David Sullivan suggests the Image-Nations poems are ‘an amalgamated nation of friends who correspond with, to, and for each other.’ And Scott Pound comments, ‘Relationality is therefore exposed, not as one might expect, through the establishment of a generality that produces ‘coherence,’ but rather through the perpetual re-opening of the series to the differences that animate it.’

Examining a poem from the Pell Mell collection, Paul Kelley neatly expands on the ‘incommensurability of worldly experience’ in his study of ‘The Iceberg’ where he considers the paradox involved in translating experience into speech, the necessary silences invoked, and the ways in which silence is composed and situated historically. His essay reminds us of Blaser’s insistence that our experience, like the iceberg whose tip represents only a tiny portion of the whole, must always address an undisclosed, much larger other, and reminds us, too, of the crucially fragmentary nature of our paradise.

Peter Middleton’s valuable essay ‘An Elegy for Theory’ on Blaser’s ‘Practice of Outside’ provides a historical perspective on Blaser’s work, exploring in detail how Blaser’s poetics emerged against the shift from the subject-based humanism of New American poets to the notion of subjectivity as linguistic projection in the post-structuralist language poets. Blaser’s influence on such prominent writers in the latter group as Charles Bernstein becomes clear in this discussion. But Blaser, Middleton shows, departs from the post-structuralist agenda in important ways. Arguing that Foucault’s stance is deterministic and antidemocratic, and reclaiming Olson from the trash heap, Middleton suggests that ‘Blaser imagines a poetry of a newly comprehended subjectivity in language, which can make effective representations in public spheres, and not simply remain closed in a verbal circuit of unbroken self-referential chains of syntax.’

Blaser asks us to imagine a syntax for the human condition that is more subtle than a world of competing fascisms. It is this question of syntax — how to put together, without foreclosing in totalitarian abstractions, the fragments of our experience, and how to maintain necessary uncertainty in mapping the real — that emerges in all of these assessments. Like Pound’s Cantos and Olson’s Maximus, Blaser’s spiritual/philosophical autobiography is visionary and wide-ranging — what Creeley calls ‘a form of taking it all.’

|

| |

Meredith Quartermain’s most recent books are Spatial Relations (Diaeresis 2001), Inland Passage (housepress 2001), A Thousand Mornings (Nomados 2002) and The Eye-Shift of Surface (greenboathouse, 2003). Her work has also appeared in West Coast Line, Raddle Moon, Chain, Sulfur, Tinfish, Ecopoetics, Potepoetzine, East Village Poetry Web and other magazines. |

| |

Works CitedBlaser, Robin. The Holy Forest. Toronto: Coach House, 1993. — — — . ‘Particles.’ Pacific Nation 2 (February 1969): 27-42. Howe, Susan. The Birth-mark. Hanover: Wesleyan UP, 1993. Wah, Fred. Music At the Heart of Thinking. Red Deer: Red Deer College P, 1987. |

|

Jacket 22 — May 2003

Contents page This material is copyright © Meredith Quartermain

and Jacket magazine 2003 |