|

Simon Smith: Denby as modernist and sonneteer. Already we seem in an unfamiliar territory, one that doesn’t quite add up because it crosses genre and literary codes of behaviour. There is a kind of aesthetic violence, a sense of the reader’s being yanked around to good, exhilarating effect. When my mum and dad came to visit New York for the first time and we took a cab from Greenwich Village to the upper Fifties, we stopped and started at every red light. Edwin’s sonnets sometimes move that way, with the stop-start of New York City. They are very contemporary (they still have that quality fifty or sixty years down the road) and traditional at the same time. Why did he choose the sonnet form?

Ron Padgett: I don’t know. Back in the 1930s the sonnet had been declared dead (by William Carlos Williams and others), though it’s interesting how many of e.e. cummings’s poems, when typographically regularized, turn out to be sonnets. Anyway, initially I found Edwin’s sometimes herky-jerky rhythms to be distracting. I think I suspected at first that maybe he was simply inept! (Like thinking that Jackson Pollock was messy.)

There may be something in what you say about New York City’s stop-and-start rhythm, which is that of vehicular traffic, but there’s also the pedestrian rhythm, which requires sudden sidesteps and swervings. But then there is also Edwin’s own dancing, his exploration of what the Germans call Grotesktanz, and his familiarity with modern dance in general. Or maybe he just had a horror of the predictability (and therefore falseness, for his purposes) of iambic pentameter. And, after all, he did like Hopkins.

Simon Smith: You’ve often mentioned Ted Berrigan in relation to Edwin. Can you describe Ted’s relationship with and enthusiasm for Edwin’s work? Did his discovery of Edwin’s work affect The Sonnets ?

Ron Padgett: When Ted ‘discovered’ a writer, he went all out to read everything that the author had published. Edwin’s published works weren’t voluminous, so Ted quickly devoured them. Then, when he met Edwin, he cajoled Edwin into lending him a typescript of the latter’s unpublished novel, Scream in a Cave. That’s how enthusiastic Ted was. He especially liked the poetry, with its New York City streets and its author writing alone in the wee hours, just like Ted himself.

Did Ted’s discovery of Edwin affect The Sonnets ? I can’t say for sure, since I can’t recall precisely when Ted latched onto Edwin’s poetry. Before he wrote The Sonnets, Ted had already studied Shakespeare’s sonnets carefully and written imitations of them, and had done a series of poems, which at first he called Personal Poems, that were imitations of Frank O’Hara, a few of which found their way into The Sonnets. Ted started writing The Sonnets late 1962, a bit before he met Edwin, I believe. In any case, I can say with certainty that Ted’s discovery of Edwin’s work confirmed Ted’s interest in working with the sonnet form.

Simon Smith: How important do you think an understanding of dance is to an understanding of Denby’s poetry? He did write poetry and dance criticism at the same time, at least in the 1930s and 40s.

Ron Padgett: The question of the interrelation of dance and poetry in Edwin’s work (and life) is a huge and interesting one about which an entire book could be written. In the interest of brevity, though, I will confine myself to saying here that if the reader knows a bit about Edwin’s interest in dance, it could be helpful in reading and thinking about his poetry. But I think it is something that should come after, not

before, a direct experience with the poetry.

Simon Smith: The question of the sonnet and Edwin’s special relationship to the form must be central to an understanding of his work. There seem to be several models I can see here. As you say, the Grotesktanz of his own dance practice, and a couple more I can see. Edwin’s involvement in film making seems crucial too. One of the impressions I have carried away from the poems is apprehension of scenes and events frame by frame, as though we are witness to the world through these poems as a series of splicings or jump cuts from an 8mm ciné film: the world on the split second moving through time.

Ron Padgett: Actually I don’t see any direct relation between Edwin’s sonnets and the quick-cutting of films. Although he was of course involved in a number of Rudy Burckhardt’s films, I don’t think of Edwin as a film person. When he went out in the evening it was to a dance performance, an art show, or a poetry reading. That is, when I knew him. Of course back in the 1930s he had translated and written several plays and had been involved with the WPA theater, but I rarely heard him talk about theater in the 1960s–1980s, unless it was something exotic like Kabuki. And though his friends had included Aaron Copland, who wrote the music for Edwin’s libretto The Second Hurricane, and Virgil Thompson, I can’t recall his telling me anything about opera. Of course he knew all about Eisenstein and other quick-cutting film directors, but when I read his sonnets I feel they are far more verbal and kinetic than visual. But I might be missing something crucial in all this.

Simon Smith: Is there a link to the boxes of Joseph Cornell, perhaps the sonnet as a box of dissonant and disparate body movements or thought movements?

Ron Padgett: Hmm, maybe, but I don’t see that either. Rudy worked with Cornell on several films, but Edwin’s sonnet poetics were set before he could have seen Cornell’s work — I’m almost certain. And I don’t see any tonal resonance between their works.

Simon Smith: Most of Edwin’s book publications have photographs by Rudy Burckhardt, either as a cover or as interludes between sections. Do you have anything you might want to say about the relationship between Denby’s and Burckhardt’s work, or about their interaction generally?

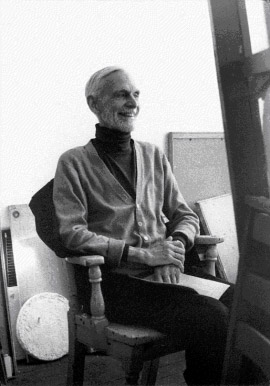

Ron Padgett: The subject of Edwin and Rudy’s friendship is vast and vastly complicated, but I can say here that their long friendship was for me and many others an encouraging example. It made me feel that aging would be less awful if one had at least one good and true old friend. When I think of their respective work and what similarities I see in that work, the word ‘modesty’ springs to mind. By modesty I mean an unassuming attitude about doing the work and having done it.

Neither Edwin nor Rudy ever, to my knowledge, promoted his own work or made any claims at all for it. Edwin even disparaged his poetry, once saying to me, ‘No one would be interested in that old stuff.’ When his poetry was finally ‘rediscovered’ and published in book form, he was, Rudy told me, secretly pleased. So in Edwin’s case I don’t think that modesty really meant a lack of confidence, nor did it in Rudy’s.

Despite their self-effacing manners, both men had very sophisticated taste and a quiet confidence in that taste. It was only very late in their lives that they began to be appreciated by a wider audience, which was all very nice, but it came too late to mean all that much. And when that appreciation brought with it a certain amount of blather, both men politely smiled and went on their ways.

Simon Smith: In your introduction to Denby’s Complete Poems you mention Dante’s Paradiso as a favourite book of his. Were there other favoured works on Edwin’s shelves?

Ron Padgett: Edwin kept very few books on his shelf. In fact, his personal possessions in general were few (though more than Gandhi’s!). Katie Schneeman told me that among his few books were Dante’s Commoedia; Tasso’s Gerusalemme Liberata; Don Quixote (in English); The Faerie Queen; The Poems of Emily Brontë; Apuleius’s L’Asino d’Oro; Sei Shonagon’s Pillow Book; Mallory’s Morte d’Arthur; and a Greek-English dictionary. There may have been a couple of others, which he gave to Bill MacKay before he died. Edwin kept only one copy of each of his own books – in a closet!

Simon Smith: Did Edwin ever give any indication of his views on what was going on in American poetry through the 1940s, ’50s, and ’60s? Obviously he had the contact and encouragement of O’Hara and the other New York poets, but what about the wider picture?

Ron Padgett: Edwin and I never talked about the wider picture of American poetry 1940–1960. He loved Frank O’Hara’s poetry — and he was terribly shaken by Frank’s death — and I know he admired John Ashbery’s work and he was close to Jimmy Schuyler, but he didn’t know Kenneth Koch all that well. Edwin was amazingly good about coming to the Poetry Project to hear young poets. It’s a bit odd that he and I never talked about that wider picture, but actually I wasn’t particularly interested in doing so, whereas I was interested in talking with him about dance and painting and music and Italy and Alice B. Toklas and Rudy. I mean I liked listening to him talk about these things — or about anything, really.

Simon Smith: What were those conversations like?

Ron Padgett: They were rambling, informal conversations we had while walking down the street, or during an intermission at the ballet, or over dinner at Rudy and Yvonne’s or George and Katie Schneeman’s, or over coffee in a diner, or after a poetry reading at the Poetry Project. I don’t remember much of what we said but I do remember the feeling and tone of Edwin’s conversation. It was light, clear, and agile, as if his thought were melodious, and as if talking about ‘high’ art were the most normal thing in the world. He did all this without the slightest trace of ego and with what I can think of only as kindness. I suspect that I’m edging here toward Edwin’s ‘nobleness’ or even his ‘saintliness,’ but he would be the first to disavow such a description.

|