|

Joe Giordano: Your eye is very... specific.

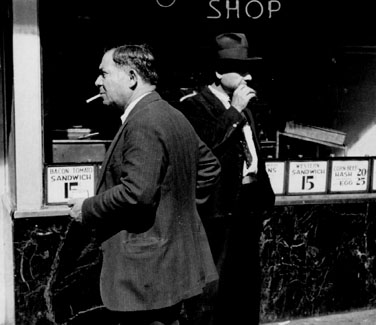

Rudy Burckhardt: I see the dirt and there it is and it comes out in the photographs too.

Joe Giordano: It’s a combination of being very specific and very objective. But there is no overlay of glamor.

Rudy Burckhardt: No, there’s no glamor. I often photograph things that I think are absolutely beautiful... most of the time actually. Sometimes I photograph ugly things, disgusting things too, or in-between, you know. Things that look really wonderful to me could be, like, a leaf, a few leaves against the sky, something like that.

Joe Giordano: I think some of the nicest things I’ve seen have been through your eyes actually. You’ve taken the camera and just rested it a moment on something that was just beautiful.

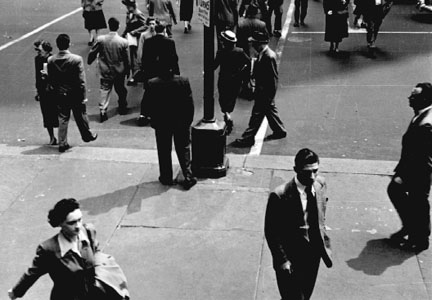

Edwin Denby: It is true, there is such a thing as real beauty, only it’s only a second that you see it. I mean, real beauty, in the sense of a fact. Now, there’s beauty in art, that is made, carefully, by a brilliant genius, and then there is... But nature itself, or life and everything, has these sudden flashes of beauty, that you do see, if you walk around, and if you’re in a good mood you know. You look up and you say ‘oh’, and then it’s gone, because something else has happened. And... that’s... It isn’t artifice, it’s just the way things are.

But, of course, you have to have a quick eye, and even if you have a quick eye, you have to have a quick camera ready. And he (Rudy) sees so many of them. He sees thousands of them. I see one or two of them now and then, and I know what it is that he has been seeing so often.

And I am at that moment perfectly happy. I don’t want anything. I have no bad feelings, you know, about myself or about other people, or about crime, or about history, or about anything. I’m just perfectly happy for the second that I see it.

Rudy Burckhardt: I suppose other photographers or film-makers, they try to make their whole work beautiful all the time and they work very hard at that. It has to be always beautiful. And that’s what glamor means, I think — that things are supposed to be on a plane which is, which usually falls apart after the novelty wears off. Sometimes I see these models in ads and they look like the most saddest, unhappiest people actually. They’re supposed to look beautiful and glamorous, but then suddenly you look into their eyes, and they seem to be absolutely suffering, more so even than other people.

Well, film is very much dependent on the audience you know. It’s just a reel in a can and it does need an audience. If you have a few good people in the audience, they can bring along a lot of other people who wouldn’t know what to think, but they’re willing to go along with the active part of the audience.

Joe Giordano: Yeah... when you see your movies, there’s always the audience. It definitely gets involved in the movies.

Rudy Burckhardt: Well, if they don’t, it’s very dreary! It’s very painful for the film-maker himself to have to see his own films, and people waking out, or falling asleep!

Joe Giordano: I want to know when you’re going to start paying your actors!

Rudy Burckhardt: Paying the actors? Right now, I should get paid, because I’m the camera-man for someone else’s movie, Philip Lopate, who is a writer who wrote this film-script. We’ll be doing it entirely his way. Nobody’s getting paid. He’s a great movie scholar. He’s seen every silent movie and practically every movie that has ever been around! And he has very strong ideas about styles of movies, and this movie is going to be in a certain style, in the style of a silent movie without being imitation of a silent movie. We’ve had lots of fun. Of course, the first day, things went wrong, but the second day, things went better.

Joe Giordano: Is this the first thing you’ve worked on in the capacity of camera-man?

Rudy Burckhardt: Sort of. Almost, I think, yes, almost.

Joe Giordano: More of your movies are being seen now, I mean, more often... Seems like almost every other month now, there’s one of your movies showing somewhere.

Rudy Burckhardt: Yeah. More than there used to be, sure.

Joe Giordano: Yeah. That’s nice.

Edwin Denby: It’s forty years!

Rudy Burckhardt: When I made them in the beginning there was hardly any place to show them. I used to rent a little loft and a hundred chairs and have a showing. And then the underground films appeared and I profited a little bit from that for a few years. My films were shown on the college and film society circuit.

Joe Giordano: How long ago was that?

Rudy Burckhardt: That was about seven to ten years ago, and I had actually some rentals, some income, from some of them. Then the explosion happened, you know, the media ‘discovered’ underground film, and then... Now so many people are making films. Now it’s much more difficult again because it’s so... so overwhelming, there’s too much around. The film scene is just tremendous. There are about three thousand film-makers graduating from college every year. And a lot of them are good, a lot of them are very good — that’s the trouble!

Joe Giordano: Well, you’re responsible for some of that!

Rudy Burckhardt: No, not really, I wouldn’t say so.

Edwin Denby: He’s responsible for some of the good ones, because they’ve been his students.

Joe Giordano: That’s right.

Rudy Burckhardt: So things always change, you know. They don’t go up and down... up for very long, then they go down, then they go up a little again.

Edwin Denby: Another difficulty was that, when the underground movies started, it was politically oriented, and that the invention of the word ‘underground’... It was called ‘home movies’, I remember, before the war, and then the serious people said, ‘oh, that doesn’t sound right, let’s call them ‘experimental’, so they were called ‘experimental movies’ during the war, and then after the war, the word ‘underground’ came up, and that was related to the underground in Europe during the war.

Joe Giordano: During the Second World War?

Edwin Denby: Second World War... the... and... it had that political connotation of showing something that could shock the apparently unshockable bourgeoisie, and make them do something about a social question.

Rudy Burckhardt: No, I don’t think the underground movies were social protest. They were a protest against Hollywood, slick Hollywood product. And they were on purpose, in this country, often very badly made, and wild, and far-out, and sexy, and it was a purely aesthetic, not social, protest. It was a protest against (the) Eisenhower fifties, The Man in the Grey Flannel Suit... A few of these, these crudely-made movies, became very celebrated. And they were fighting censorship, you know. Jonas Mekas got arrested, and some other people did, for showing...

Edwin Denby: Flaming Creatures.

Rudy Burckhardt: Flaming Creatures... and Genet movies. It was a wild time. And they really won the fight against censorship, and censorship in film, is, was, completely defeated, and they were really instrumental in that.

Well, my movies never really fitted into that category either because they might have been unprofessionally made but they were not really protest, they were not controversial actually at any time, they were just something completely different from Hollywood product. But they got a little bit... They could ride a little bit on the vogue of underground movies for a while.

Joe Giordano: Do your consider you movies ‘underground movies’?

Rudy Burckhardt: I always liked the word ‘underground’, yes. I like it better than ‘experimental’ movies, or ‘creative’ movies, or ‘chamber’ movies, or ‘personalized’ movies, or whatever it is — ‘independent’ movies.

Joe Giordano: I read where you said you like the word ‘movie’ better than ‘film’.

|