|

Jacket 20 — December 2002 | # 20 Contents | Homepage | Catalog | |

Neil Reeve and Richard Kerridge

Deaf to Meaning:

|

|

|

The shut inch lively as pin grafting

‘Lively’, ‘at a loss’, and later ‘in a twinkling’ reflect the quick staccato bursts, the tone of terse suggestiveness: ‘You cut your chin / on all this, like club members on the dot / by a winter blaze.’ One may think of ‘cut your teeth’ — of initiations, openings, joining clubs — but has only a moment to wonder why teeth have become ‘chin’ before being hurried on by the drive of the words, towards ‘in a twinkling mind you, to pick up / elastic replacements on the bench code’. Our first reading tools are already taken over by ‘replacements’; there is always going to be that double sense, of what is simultaneously felt to be given and taken, offered and snatched back. It seems moreover that one source of the energy and momentum in the text will derive from regular hints that it is self-consciously anticipating the reader’s struggle to stabilise his or her reactions. For much of the time the poem seems to be dancing ahead, beckoning us to keep up with it. The penultimate section, for example, appears to offer a kind of ironic commentary on the very difficulties it imposes: In darkness by day we must press on,

‘It is not so hard to know as it is to do’ stands out, in its simple bluntness, to warn the interpreter against self-satisfaction. But it does seem possible to observe the transition from ‘giddy’ (line 2) to ‘poised’ (line 12), as the two words face each other symmetrically across the poem. The active participles indicate involuntary or uncontrolled movement — ‘swaying’, ‘wresting’, ‘spilling’ — and in each case occur in phrases which could refer to stressful quests for information: trying to lip-read in uncertain light, or apparently struggling to catch something on screen before it disappears, or discovering, with suitable chagrin, that what at first sight seemed so promising (‘petals’) were only the records of where value had been (‘cheque stubs’). Halfway through comes the cry for relief from these stresses, ‘Pity me!’, because what ‘at the last we want’ is for the Gordian knot of such frustrating difficulties to be cut, for everything to be properly accounted for and audited (‘unit costs plus VAT’). Our desire is for ‘patient grading’, which could suggest either the careful sorting of items into their appropriate places, controlling the instability that makes us giddy; or something like the battlefield triage of the army medical corps, where patients are graded into more or less urgent cases. The knowingly general tone of ‘at the last we want’ makes us accomplices in a resentment derived perhaps from an over-pampered life (some further implications of that are discussed later). But at least we can regain some ‘poise’, because our impatience with complexities goes with an eagerness to assert our control, to rub everything down (with ‘sugar soap’) ready to paint it over again. |

| |

Otoconial crystals

|

|

These crystals are responsible for providing the brain with information as to the position of the head within the earth’s gravitational field. They begin to develop around the tenth week of gestation, and by the twenty-sixth week are virtually fully-formed, sending impulses to the brain at a prenatal stage when the eye and the auditory ear are still quite limited in their functions (although recent research suggests that the auditory ear begins its active life earlier than was previously believed). The otoconial mass does not form itself into a finished state which then remains unaltered throughout life. It constitutes instead a continuously developing system of combinations and replacements whose end is to measure and promote the stability of the organism. The American psychologist David Hubbard, a follower of Schilder’s pioneering work on the role of gravitational awareness in the formation of human personality, pointed out this apparent paradox: ‘Had nature intended true ‘ear stones’ of unchanging characteristics, a single large crystal with maximum mass and smallest surface area might have been designed. Exactly the opposite structure and possibilities exist, with a system comprised of millions of small crystals offering a large total surface area for chemical interaction. Moreover, had the system been designed to be static, the crystals would have been deeply buried behind an impermeable barrier rather than surrounded by membranes containing active ion pumps operating in a fluid of nearly neutral pH (we should remember that calcite is readily soluble in solutions of pH less than 7)’ [Note 2] |

| |

Otoconial crystals

|

|

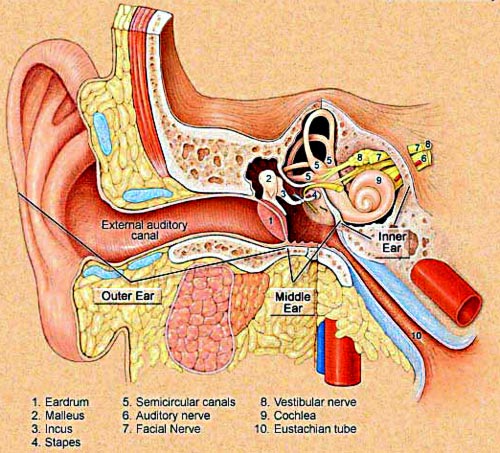

Hubbard saw the otolith crystals as ‘physical particles which symbolically represent the outer world’. They comprise the ‘organ’ through which ‘gravity speaks’. The suggestion seems to be that, by registering the laws of gravity upon the human brain, the crystals act as agents of a primal encounter with external reality, a negative point or limit for the ego’s aspirations (in this case, to fly or to float). They mark one of those threshold sites at the rim of human identity, across which pass the fundamental processes which enable us to have our being. In a previous article (The Swansea Review, no. 4, Jan.1988) we discussed the general interest in such processes that distinguishes Prynne’s poetry; in this particular case the ‘oval window’ itself, the aperture in the middle ear through which sound waves travel to be transformed into neural impulses, is another point at the edge of what constitutes the integrity of the human subject. |

| |

Diagram of the ear - copyright Northwestern University

|

|

Such processes, whether neural, molecular, economic, geological, or political, can rarely be brought to consciousness in the moment of their effect, and normally require special conditions and equipment in order to be observed or measured. Nor are they readily accounted for in materialist terms alone. The otolith crystals, for example, could be said virtually to constitute the point where mind and matter start to intertwine, and such categories lose their homogeneity. In this case, moreover, we have something more complex than a threshold or a boundary post. The crystals, along with other parts of the vestibular apparatus, not only mark the edge of the organism, but act as a safety check built into it, warning against inappropriate or destabilising activity — from outside, by giddying disturbances, or from inside, by overreachings. The continuous chemical exchanges of the otoconia, reacting to the tiniest nuance, are as Hubbard describes them part of a process of constant re-orientation of the organism in the face of upsets; and in this way they offer a special kind of analogy for — or affinity with — the experience which The Oval Window offers — the experience of recurrent tension and interplay, as in the section quoted, between the ‘giddy’ and the ‘poised’, in all their forms and associations. |

2

There are frequent references in the poem to the languages used by information-processing systems which have their own internal safety-mechanisms, and which apply pre-organised or programmed responses to the variable data they meet with. There are several phrases from computer terminology, for example. These phrases are not included merely as obscure bits of specialised discourse, designed to baffle the lay reader, or to glow with the romance of the elite group who have privileged access to what for the rest of us may be meaningless. They are also used in much the same way as the computer itself would use them: From the skip there is honey and bent metal,

An array is a reserved block of computer memory. A programme can specify that the computer should reserve, before it proceeds, so many memory locations as space left available for future use. If more subscripts are fed in than there are locations available, a subscript will crash the programme by colliding with something already there. The warning demand to ‘check’ signals that the processing system is about to be overloaded, unless there is a deliberate intervention, an adjustment to control the flow. A view is a window

The market designates as ‘erratic items’ commodities like diamonds and aircraft, whose irregular sale and delivery dates cause blips in the monthly trade figures; here the phrase becomes progressively ironic, or merely inadequate, given the list that follows it. If we try to pursue the syntax, it seems to say that such designations comprise not a genuine view of reality but a separate copy of it, in which phenomena or ‘data’ can only appear if there are categories for them already in place. ‘Changes to the real data’ — which might be all sorts of things; a revolution overseas, perhaps — are processed only as influences on prices and surpluses, whose adjustments are in turn fed back into the real to influence it; while at the same time there could be the suggestion that such regulating systems create a world of their own which masquerades as the real one, or becomes virtually indistinguishable from it. Either way, the computers, the insurers, the stock dealers proceed without wavering or digression, reading the incoming ‘data’ by means of automatic and passionless conversions and reconversions, predetermining which items will pass into the system and in what ways they will register there. |

3

The skip was the place where all these unwanted bits had been dumped. ‘From the skip there is honey and bent metal’ (p.19) — a strange assortment of debris in the one container. Perhaps poetry is able to feed on precisely the meanings that other systems have no use for; these are poetry’s ‘honey’, still available because other purposes have skipped or looped past them. Modernist poetry has frequently found itself picking over, in a kind of redemptive scavenging operation, what from other vantages might seem to be refuse or trash, in order to see what kind of life could still be gleaned from it. A chaotic tangle of phrases in a heap can in addition offer possibilities of survey denied when those phrases are working self-sufficiently. But though it often seems so, the language-tangle in The Oval Window is rarely a random colliding of discards, or the residue of a crashed programme. The most sustained merging or editing together of separate texts has an extraordinary intricacy, when on pages 23-24 a speech from All’s Well that Ends Well wanders in and out of the poem’s territory: Hold your chin

The italics are ours, simply to clarify the arrangement of the words. This speech is made by the clown Lavatch, while the Countess and Lafew are bewailing the apparent death of Helena, and Lavatch’s contribution, with its sarcastic talk of hell-fire, the afterlife, future hopes and spiritual insurance, is characteristically tactless. some that humble

None of the other concatenations of the two texts has quite the self-sufficiency of this. If it were delivered in a sardonic, sneering tone, Lavatch’s tone, it would point out how some readers, in a spirit of misplaced reverence, invest poetry with superior powers and thereby enchant themselves, unable to recognise the constructed or pre-programmed nature of their responses. But at the next glance, the lines carry a note of conviction unhindered by the instant edits and replacements which predominate elsewhere in the poem, a note which perhaps sanctions an almost literal reading — that some may allow the poetry to work its magic, its revelation of truth and pleasure, by being willing to abandon their proud demands on it and by setting their egotisms aside. Since none of the strands of entwined text can ever gain supremacy, or come into being without its accompanying contrary, we veer again from side to side; any of the positions taken up in the play of alternatives could be ‘Either contract / or fancy, each framing the other, closed / in life.’ (p.31) The word ‘framing’ moreover also splits in two, since it can mean both fixing a margin around something, and concocting a false charge against it. The bond of trust and hope involved in a ‘contract’ is both surrounded and unjustly yet plausibly accused by the whims and self-entrapments of the ‘fancy’, while the former reciprocates, in a continuous and seemingly interminable pattern, ‘closed in life’. 4

This section had set out with ‘it is joined’; the next starts ‘As they parted’. As with the tilting crystal, the moments of clarity or convergence are short-lived. Once again consciousness can only briefly inhabit the ‘place’ apart, and glimpse the vision it affords, before the forces which were held there in a kind of balance resume their momentum. There are various Romantic traditions of negotiating a place for the self, a place of at least provisional stability, amidst the boundless organicism of the world, and The Oval Window seems to touch on them when, shortly afterwards, we come across what appears to be a rough shepherd’s hut: It is not quite a cabin, but (in local speech)

There is a picture on the book’s cover of some such dry stone building, which would appear, like so much indeed of the poem’s text, to be in the process of disintegrating — or reintegrating — back into the environs from which it was constructed. It would offer some rudimentary shelter and a prospect on the surrounding landscape, like a Wordsworthian occasion for reflection and insight (it is hard not to think of the ruined cottage in The Excursion, or the heap of stones in Michael). It is a type of temporarily secured area, providing a vantage-point from which the continuous movements of the world’s processes could be acknowledged, without the acknowledging self’s being instantly dissipated by them. The Oval Window had begun by pointing such a position out, somewhat ruefully: ‘What can’t be helped / is the vantage, private and inert’(p.7). The tone seems to lament the fact that we cannot avoid occupying protected positions to see from. ‘Private’ and ‘inert’ are relative terms, however, liable to dissolve on closer scrutiny. The pressure of those continuous movements will sooner or later put both our privacy and our stillness in jeopardy, and hence this vantage also ‘can’t be helped’ in the sense that arises at the very end of the poem: it is ‘beyond help’ (p. 34), and can be neither avoided nor preserved. It constitutes much the same temporary relief as the ‘fire break’ (p.12) afforded the stockdealer. deaf to meaning, the life stands

Certain ethical implications of this position, this decentering of man to allow his ‘measure’ (Heidegger’s term) to be taken, instead of his measuring being imposed on things, are recurrent in Prynne’s work (and are obviously central to the modernist tradition he is aligned with — Olson for example, or the Pound of the Pisan Cantos). In The Oval Window, amidst man’s giddiness and ‘control flow structure’ (p.19), ‘The arctic tern / stays put wakefully, each following suit / by check according to rote’(p.18). To stay put wakefully, to have patience which is not passive lethargy, repose which is alert and vigilant rather than timidly self-protective, would be a control flow structure of a quite different order — something close to what Heidegger meant by ‘dwelling’, a kind of reverential letting-be and letting-come of the world in which man was properly rooted. oilseed

There is a good deal of abrasive sarcasm in the first half of The Oval Window, some of which has a specifically early-1980s British political edge to it, with the persistent tones of free-market cynicism and the use of highly-charged phrases like ‘safe in our hands’ (p.9), ‘pay-bed’ (p.17). But one could not confidently trace a consistent attitude in it, any more than in Lavatch’s, and it is just as likely to collapse into anarchic humour: the view

‘Think now’, Eliot wrote in Gerontion, ‘History has many cunning passages’. The bird and the ‘control nesting’ anticipate the arctic terns on the following page (although one computer programme can also be ‘nesting’ inside another). At the instant that ‘keep mum’ colloquially denotes silent complicity in such interference, an unthinking acceptance of a ‘reason’ to control and cut back the levels of procreation, isn’t it also the plaintive cry of someone protesting about thus being deprived of his mother? So much in Prynne’s poetry pulls both ways at once that whenever we want only the figurative in such phrases the literal refuses to lie down. At the last we want

We noted earlier how this penultimate section of The Oval Window seemed to be casting a backward glance over some salient features of the text, offering an ostensible drawing-together or promise of orderliness whose viability was promptly put into question. The ironic presentation of our impatient wish, as readers, for everything to be ticketed and labelled, applies now perhaps more widely: do we really ‘want’ to be ‘made to care’, to have our humanity brought out in such a constrained and automatic way as is suggested by ‘made to order’, as if by a customised package or a physical reflex? A similar dilemma seems to be posed by another passage which interweaves evocations of health care management with ‘reflex’, ‘skip’, and the strains on reading: Skip and slip are the antinomian free gifts

The antinomians believed that since their salvation was preordained they were exempt from the moral laws binding upon ordinary humans — which again makes skipping round things or slipping past them sound like the kinds of dubious freedom conferred on the elect that we had with the Nazi slogan. That such gifts should be ‘mounted on angle-iron reflexes’ suggests that what is claimed to be ‘free’ here is in fact as fixed and inflexible as a Pavlovian reaction. In the second clause a ‘check’ could mean simultaneously a test, an obstruction, or a bank draft; in all three cases the payment is predated, made in advance, because the system of sick pay discounts ‘recovery’. It operates on the presupposition that since a recovery will eventually occur, it has in a sense already occurred. In this way, like other systems elsewhere in the poem, it effectively skips round or slips past the actual problem. The sickness itself is not permitted to have a unique nature calling for a special response, but is regarded merely as an item of data to activate the system. You’re flat out?

The view becomes increasingly bleak, as the universality of ‘the method’ forms a circuit running right through the economy to infiltrate all areas of life. There is no choice where choosing is compulsory, and where what is to be chosen is an ‘order’ to pay now, ‘on the nail’. Alternatives seem to have been dismissed by another moment of Thatcherite rhetoric: ‘What else null else’. If exhaustion (‘You’re flat out?’), or accident (‘overshoot’) should drive us into the ‘garden’, even our relief is presented sardonically. After so much metallic grinding in the verse here, with its angle-irons, wire and nails, its relentless pressure, the moon’s liberating brilliance exhilarates us for a moment. But in terms of the social grid the intervention of such natural brightness ‘ranks as a perfect crime’, insolently disrupting the uniform pattern of organised street lighting (‘perfect crime’ hovers between two tones, a kind of grim satisfaction for the rebel, and slightly camp outrage for the upholder of convention, without quite committing itself to either). The ‘method’ seems by this stage to be continuously eroding our efforts at meaning, difference and freedom alike: ‘So what you do is enslaved non-stop / to perdition of sense by leakage / into the cycle’(p.18). 5

If there is a quest in the poem for alternative responses to the world, Heideggerean or otherwise, which are not artificially stabilised by controlling circuits and mechanisms, then one might expect, as was mentioned earlier, to be able to trace it through natural imagery drawn from the Romantic storehouse, such as the moon and the snow shining here. But, characteristically, just as we reach a ‘point of entry’ (p.9), the structure tilts again, and our tracing leads us into a quite different territory. As we move beyond the turning-point of the Lavatch section into the latter part of the poem, these apparently natural images — snow, moonlight, blossom, mist — start to proliferate and repeat themselves to the point where their integrity as natural signifiers is lost. They find themselves being absorbed into the increasingly predominant network of borrowings in the text from a certain form of Chinese poetry. It is this, rather than the glimpses of Western Romanticism, which really creates the new mood of spaciousness and serenity in the second half of The Oval Window. It produces a number of neatly-contoured phrases which stave off the threat of disintegration much more effectively than before: Her wrists shine white like the frosted snow;

Such lines, along with several others, very much resemble English renderings of the ‘Palace Style Poetry’ of the Southern Dynasties, which Prynne discussed with considerable erudition in a critical essay appended to Anne Birrell’s translation of the anthology New Songs from a Jade Terrace. In this kind of writing the frequent references to nature are essentially functional, operating within a highly stylised poetic code. Landscape, for example, ‘is not so much a source of images for contemplation as rather a set of tropes for the separation of lovers by the hardships of distant travel’ [Note 5] — which separation is of course itself a trope, by its self-disarming frequency, for something private and unspecified. Autumn is by convention the season of partings; a reference to willows implies a desire to prevent someone from making a journey; the window itself, marking a more severe distinction than any normally found in the West between inside and outside, is the place from where the lonely, isolated woman, shut up in an indoor world of cosmetic surfaces, gazes more or less helplessly for signs of her departed lover (‘Tunnel / vision as she watches for his return’, The Oval Window, p. 30). the echo trembles like a pinpoint, on

The Chinese screen would be ‘heartfelt’ from the emotional charge carried — and in a sense carried away — by its symbolic landscape paintings. Western conversion systems tend to leave passion to wander unattached, so that eventually, like an unwelcome intruder, it sidles up to a host who tries not to recognise it; a kind of equivalent to the Palace Style mists and mountains might be the snippets of forensic reportage: ‘when the furniture was removed / he pulled out the window frames, threw down / the roof, and pushed in the walls’ (p. 17) — which almost buckle under the pressure of everything their dispassionateness is trying to keep out. They appropriated not the primary

In their own way such statements reinforce the stress Prynne’s essay places on the uniqueness of that culture and the resistance of its forms to the easy extrapolations translators like Pound and Arthur Waley indulged in. The problems of care and precision introduced both by this discourse and by the metonymic usages surrounding it bear on a more general and recurrent issue in Prynne’s work: one of the sensations released by reading a poem like The Oval Window is quite simply an awareness of the large, sometimes overpowering consequences that can be brought on by the slightest changes — whether these be the least displacement of an otolith crystal, or the skipping of a letter in a programme; and hence the question as to whether a kind of insensibility, or a deliberately cultivated indifference to that awareness, becomes a necessary factor in human survival. Looking at the misty paths I see this stooping

The flakes make the figure sublime, or take it beneath conscious perception. We cannot make it out clearly because of the faltering and adjusting as it struggles to keep its balance on treacherous and slippery paths. The white-out erases, or leaves subliminal, whatever we thought we had seen — at which point, ‘snow-blinded, we hold our breath’ (p.27): ‘the echo trembles like a pinpoint, on / each line of the hooded screen. It is life / at the rim of itself’ (p.27). We strain intently for a kind of radar evidence of the very extremities of life, identifiable on a screen when they are no longer accessible to the senses. Standing by the window I heard it,

‘The crossing flow / of even life’ sounds like a climactic vision of equilibrium, as continuous transversal waves and pulses, moving through both space and time, pass over the ‘fold line’, the turning point where speed and direction alter. Everything that gathers here, everything that is part of the ‘flow’, is ‘free / to leave at either side’; it all ‘runs in / and out and over’ (p.28) the entries and exits, like the oval window itself, that open and close throughout the poem. So much material, from the years both of an individual life and of a longer perspective, so many glimpses of meaning, ‘jostle and burn up’ in their mutual abrasion, but the tone of the lines seems to celebrate the kind of continuity which death itself cannot close. — N.H.Reeve (University College of Swansea) & |

NotesNote 1. The Oval Window (Cambridge, 1983), p.33. Note 2. D.G.Hubbard & C.G.Wright, ‘The Emotion of Motion: Functions of the Vestibular Apparatus’, in Paul Schilder, Mind Explorer, eds. Shaskan & Roller (Human Sciences Press, 1984), pp. 180-81. Note 3. Martin Heidegger, Poetry, Language, Thought, trans. Hofstadter (New York, 1971), p.226. Note 4. John Sallis, Heidegger and the path of thinking (Pittsburgh, 1970), p. 148. Note 5. J.H.Prynne, ‘China Figures’, postscript to New Songs from a Jade Terrace, trans. Anne Birrell (Harmondsworth, 1986), p. 374.

Note 6. ibid., p. 381. |

|

Check out this author’s work: Bookstores in Britain, and in the United States This material is copyright © Neil Reeve and Richard Kerridge

and Jacket magazine 2002 |