|

Jacket 20 — December 2002 | # 20 Contents | Homepage | Catalog | |

George Watson: Remembering PrufrockHugh Sykes Davies 1909–1984Back to Hugh Sykes Davies Contents list

First published in the Sewanee Review, vol. 109, no. 4, Fall 2001. |

|

He had done so many things and played so many parts that you never felt you had come to the end of him. Some knew Hugh Sykes Davies as a wit, some as a lover, some as a teacher; and there were those who read his novels and even his poems. He also married a good deal. He had many wives, four of them his own; taught at Cambridge for nearly half a century — a communist for half the time; was a surrealist in the Paris of the mid-1930s; and finally, as faith and dogma ran dry, a structural linguist. He was once to have been a candidate for the House of Commons too, in 1940, in an election canceled because of invasion fears. |

| |

|

|

In 1959, when I first met him, he would soon turn fifty. He chaired an English department I joined that year. By then literature interested him only spasmodically. The real passion of his life was fishing, which induced a state of passivity, he would say, almost of nonbeing, not otherwise to be achieved. He loved his motorbike too, till his wife and his mother joined forces to make him give it up. At his age it was too dangerous, they felt. He probably felt it was not dangerous enough, since it was danger above all that attracted him. He loved doing things he could not quite do, such as writing fiction or playing the accordion. If it was not new — new to him — it was not interesting. Thought had to be dangerous too, in a high theoretical way. ‘One must always have a general analysis,’ Hugh once remarked to explain why, after socialism had failed, he took to structuralism. A love of novelty explains his marital career, which began with the poet Kathleen Raine and ended by his remarrying his third wife as his fifth. It was not a return but something new, since he had not remarried anyone earlier; and besides she was related to a baronet. ‘Every time I marry her I get into Debrett.’ |

| |

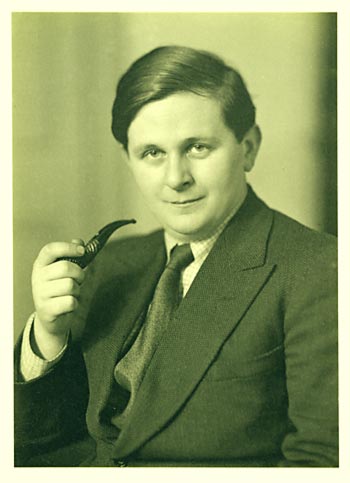

Hugh Sykes-Davies |

|

His friendships with the not-yet-famous were numerous. Before the war, which caused C. P. Snow to move to London, Hugh spent many convivial hours with him, though he found Snow laborious in conversation and delighted in mockingly calling him Percy instead of Charles. He drank with C. S. Lewis, avoiding topics that involved their conflicting opinions, such as religion and communism; and he enjoyed discussing the Italian comic epics, though he occasionally found Lewis overly disputatious. He had known Maynard Keynes, though he took no interest in economics, and Henry Moore, a fellow Yorkshireman still unknown as a sculptor. In fact for a time he lived in north London with Moore and his Russian wife, Irene, and would tell how the sculptor would go down to his basement studio after breakfast and light a cigarette. Carving, however, is a noisy business, and Irene was ambitious. ‘Henry, what are you doing?’ she would shout repeatedly down the stairs, with rising emphasis, until he reluctantly threw away his cigarette and took up his chisel.

A bohemian life meant escape from the factories of Yorkshire and the stolid parsonage where his family, who had been Methodist before they were Anglican, practiced the strictest abstention. In fact his grandmother’s middle name, he delighted to recall, had been Abstemia. A freshman in 1928, he found Cambridge a liberation, and spent the rest of his life defining himself against the values of a puritan childhood, discovering the virtues of abstention only when it was too late to matter. He had lost his virginity at a remarkably early age at a boarding school, when a nurse brought in to deal with an epidemic had been rashly allowed a latchkey, and he never forgot his anxiety, as he crept back after his first amorous adventure, wondering whether it would impair his performance at football. |

| |

Hugh Sykes-Davies |

|

Cambridge put him at eighteen into the middle of the only school of critical theory on earth, and he adored a new theory even more than solid or liquid stimulants and in much the same way. In the heady days of I. A. Richards, theory could turn you on and help you drop out, which he did, editing an undergraduate journal called Experiment with his fellow student William Empson. |

| |

|

|

Photo of William Empson (at right of group) copyright © the Master and Fellows, Magdalene College, Cambridge, courtesy the Pepys Library, Magdalene College

It was a critical school dedicated to T. S. Eliot, then a young American in London; but he broke with Eliot over religion, and, at Eliot’s death in 1965, Hugh wrote an obituary called ‘Mr. Kurtz, He Dead,’ in which Conrad’s bitter epitaph in Heart of Darkness sums up an abiding sense of betrayal. Kurtz had exterminated natives in the Congo, and Eliot’s Anglicanism seemed to Hugh hardly better; worse still his equivocal attitude to Franco during the Spanish Civil War and his fellow feeling for Marshal Pétain after the fall of France in 1940. The Vichy slogan Family, Fatherland, Work summed up everything Hugh did not believe in, and quite a lot that Eliot did. Not that Eliot rejoiced in the defeat of France. ‘But he did think it an opportunity,’ Hugh said sadly, ‘to do something interesting.’ Eliot had taken a path his disciples could not follow. |

| |

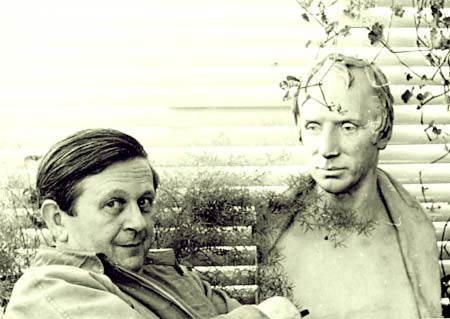

Hugh Sykes-Davies with bust of Wordsworth |

|

These were his spots of time, as he called them, quoting his beloved Wordsworth, and like Wordsworth he felt their vivifying virtue. Wordsworth, he once explained in a collection he edited called The English Mind (1964), was a precursor of Freud, whom he had met in Paris in 1938 in the home of Princess Marie Bonaparte, ‘the only princess I have ever known’ and head of the French Freudians. Freud was a refugee on his way from Vienna to London, where he died; and like Wordsworth he had seen experience less as a continuum than as a broken chain of crises and traumas, a shattered record where almost all the fragments are jettisoned as meaningless, the remaining few to be interpreted and reinterpreted into patterns of healing significance. That is what Wordsworth’s Prelude is about, and Proust’s great novel, and that is how Hugh too saw time, in its aimless passage from a birth you cannot remember to a death you will never recall. |

|

Check out this author’s work: Bookstores in Britain, and in the United States This material is copyright © George Watson and Jacket magazine 2002 |