|

Jacket 20 — December 2002 | # 20 Contents | Homepage | Catalog | |

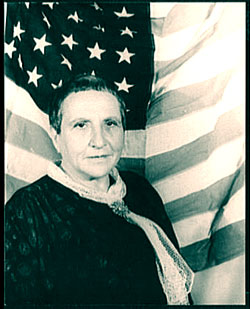

Hugh Sykes Daviesreview of Narration, by Gertrude SteinBack to Hugh Sykes Davies Contents list Narration. By Gertrude Stein. (The University of Chicago Press.) 11s.6d. [Eleven shillings and sixpence.] |

|

This piece was first published in ‘Books of the Quarter’,

Not many years ago, Miss Stein was honourably mentioned in most lists of the leaders of modern literature, even short ones, and was often seen in the company of greater than herself — on paper. There was some justification. She had evolved from herself, from her own sensibility, an original means of expression, and she had developed it skilfully within its rather narrow limits. Her achievement was obviously not great, but as far as it went it appeared to be genuine, and that is more than can be said for many more pretentious experiments. |

| |

|

|

Some of the most attractive minor pieces in all the arts have been produced by such talents, limited, but within their limitations real and complete. There is unfortunately the danger that an artist of this kind may some day refuse to accept his limitations honestly. For the emotional reactions which follow any genuine creative activity, even on a small scale, are often productive of spiritual pride, and spiritual pride is a great solvent of honesty. It is to be feared that something of the kind has happened to Miss Stein. Disregarding her limitations, she has attempted tasks which she does not understand, and which she could hardly perform even if she understood them. This book on narration marks the nadir—if we are lucky—of this sad decline in honesty. There is this to be said in excuse, that the temptation to exceed herself came from others. In his introduction Mr. Thornton Wilder says that the four lectures which compose the book were delivered at the University of Chicago, and that body must take a little of the blame for issuing such an irresponsible invitation. But Miss Stein must take much more of the blame for accepting it. ‘Poetry and prose, I came to the conclusion that poetry was a calling and intensive calling upon the name of anything and that prose was not the using the name of anything as a thing in itself but the creating of sentences that were self-existing and following one after the other of anything a continuous thing which is paragraphing and so a narrative that is a narrative of anything. That is what a narrative is of course one thing following any other thing.

What of the syntactical resources of poetry? And of the semantic function of words in prose? But perhaps in some obscure way objections such as these are met by Miss Stein, and I have been too stupid to see them. Even so, I can feel little shame at failing to understand a passage which displays such deplorable looseness of thought. It is enough to examine the variations of meaning of the word ‘thing’, both singly and in its compounds ‘anything’ and ‘everything’. Apparently it can stand for the subject matter, the object described, a proposition by Miss Stein, or the preceding sentence as a whole. No theory can be expressed clearly through such confusion, nor can it exist clearly. And unhappily the other subjects treated in the last two lectures are just as shabbily handled as this matter of prose and poetry. I see that Miss Stein has discussed the newspaper, history, the novel, biography, and autobiography, but I do not know what she has said about them. Everywhere is the multum-in-parvo ‘thing’, running through the whole gamut of its nebular meanings, just as it does with children who are learning to talk, or with stupid women who try to discuss intensely subjects which they do not understand. |

The confusions of thought are made worse by Miss Stein’s habit of omitting all facts and illustrations. Mr. Wilder puts a very good face on it by assuring us that ‘Miss Stein pays her listeners the high compliment of dispensing for the most part with that apparatus of illustrative simile and anecdote that is so often employed to recommend ideas. She assumes that the attentive listener will bring, from a store of observation and reflection, the concrete illustration other generalization.’ But all that is mere euphemism. It would be better to say that Miss Stein spins a web in the void, either ignorant of facts or not caring for them.

Her generalizations do not perform the function of organizing our data, for we can never know which data she has in mind. Her theories are their own reward. Perhaps they merit the title of ‘pure theories’, for they are completely untainted by facts or concrete knowledge. ‘I had a funny experience once, this was a long time after I had been writing anything and everything as you all more or less have come to know it, it was about five years ago and I said I would translate the poems of a young French poet.... so I began to translate and before I knew it a very strange thing had happened.

It is dreadful to think that growing minds should have had before them such an example of loose thinking and bad criticism. |

|

|

|

Check out this author’s work: Bookstores in Britain, and in the United States This material is copyright © the Estate of Hugh Sykes Davies and Jacket magazine 2002 |