|

Jacket 17 — June 2002 | # 17 Contents | Homepage | Catalog | |

|

Back to the

Ern Malley

David LehmanThe Ern Malley Poetry Hoax — IntroductionThis piece was originally published in Jacket 2. |

|

The complete poems of Ern Malley (without the ‘Preface and Statement’) are published in the Northern Hemisphere in The Bloodaxe Book of Modern Australian Poetry paperback: 474 pages ; Publisher: Dufour Editions; ISBN: 1852243155, via Amazon; |

|

THE greatest literary hoax of the twentieth century was concocted by a couple of Australian soldiers at their desks in the offices of the Victoria Barracks in Melbourne, land headquarters of the Australian army, on a quiet Saturday in October 1943. The uniformed noncombatants, Lieutenant James McAuley and Corporal Harold Stewart, were a pair of Sydney poets with a shared animus toward modern poetry in general and a particular hatred of the surrealist stuff championed by Adelaide wunderkind Max Harris, the twenty-two-year-old editor of Angry Penguins, a well-heeled journal devoted to the spread of modernism down under. |

| |

|

Artist Joy Hester and editor Max Harris on the train from Melbourne to Heide, circa 1943. |

|

In a single rollicking afternoon McAuley and Stewart cooked up the collected works of Ernest Lalor Malley. Imitating the modern poets they most despised (‘not Max Harris in particular, but the whole literary fashion as we knew it from the works of Dylan Thomas, Henry Treece, and others’), they rapidly wrote the sixteen poems that constitute Ern Malley’s ‘tragic lifework.’ They lifted lines at random from the books and papers on their desks (Shakespeare, a dictionary of quotations, an American report on the breeding grounds of mosquitoes, etc.). They mixed in false allusions and misquotations, dropped ‘confused and inconsistent hints at a meaning’ in place of a coherent theme, and deliberately produced what they thought was bad verse. They called their creation Malley because mal in French means bad. He was Ernest because they were not. |

| |

|

Photo of a man believed to be Harry Palmer, Ern Malley's employer at Taverner's Hill, circa 1941, courtesy New South Wales Mechanics' Institute archives. |

|

Ern (she wrote) had been born in England in 1918, was taken to Australia after his father’s death two years later, and was left in Ethel’s care after their mother died when he was fifteen. Having dropped out of school, the young man worked as a garage mechanic in Sydney and later as an insurance salesman and part-time watch repairman in Melbourne. In 1943 he returned to Sydney, where he died of ‘Grave’s Disease.’ |

| |

|

Photo of Ethel Malley (right) with neighbour's child and dog "Tray", Burwood, Sydney, Australia, 1944 |

|

Artless Ethel, the bourgeois philistine, had the effect of authenticating Ern’s poignant existence. The simplicity of her account inspired Harris to construct the poignant life-story of a poet who burned Keats-like in a flame snuffed out before its time. ‘The weeks before he died were terrible,’ Ethel wrote. ‘Sometimes he would be all right and he would talk to me. From things he said I gathered he had been fond of a girl in Melbourne, but had some sort of difference with her. I didn’t want to ask him too much because he was nervy and irritable. The crisis came suddenly, and he passed away on Friday the 23rd of July. As he wished, he was cremated at Rookwood.’ |

| |

|

Photo believed to be of ‘Ern Malley’ as a boy (right), with sister Ethel and neighbour's child, Petersham, Sydney, Australia, 1927 |

|

Ern Malley was just what the avant-garde ordered: a tragic hero. His poems were charged with the premonition of an early death and the conviction that poetic greatness would be his if he could but live five more winters. McAuley and Stewart saw to it that Malley had, like Keats, died at the age of twenty-five. ‘Now in your honour Keats, I spin / The loaded Zodiac with my left hand / As the man at the fair revolves / His coloured deceitful board,’ Malley writes in ‘Colloquy with John Keats.’ And, Like you I sought at first for Beauty Amid the red herrings scattered in the poems, McAuley and Stewart did sprinkle a few genuine clues to the mystery of Ern Malley. From ‘Sybilline,’ for example, these splendid lines hint at Malley’s ghostly nature: It is necessary to understand It was, however, possible to take these lines metaphorically as the dying man’s vision of impending oblivion and posthumous applause. |

| |

|

|

Malley is a comedian of the spirit, who wards off self-pity with defiant irony. But he also has a prophetic voice and a grave historical vision, as in these haunting lines from ‘Petit Testament’: ‘But where I have lived / Spain weeps in the gutters of Footscray / Guernica is the ticking of a clock / The nightmare has become real, not as belief / But in the scrub-typhus of Mubo.’ And he is capable of the pure lyric outcry. Here is the second stanza of ‘Sweet William’: One moment of daylight let me have

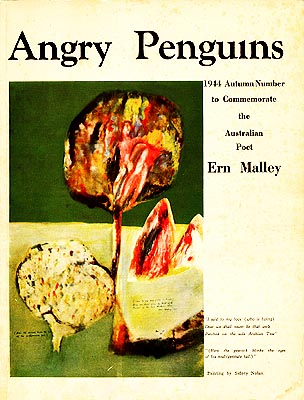

Harris fell for Malley hook, line and sinker. So did his patrons and chums, including the painter Sidney Nolan, who would become the most celebrated Australian painter of his generation. They devoted the next issue of Angry Penguins to their excited discovery — and were promptly ambushed by the hoax’s exposure in the press in June 1944. Although this was scarcely a slow news summer — the Normandy invasion took place in June, the liberation of France in August — the story spread rapidly to England and America, and everywhere the reaction was the same: high hilarity at the expense of the Angry Penguins, the humiliation of Max Harris, a colossal setback for modernism in Australia. The hoax was, as Michael Heyward points out in The Ern Malley Affair (London: Faber & Faber, 1993), a decisive act of literary criticism, brilliant parody in the service of fierce polemic. If, as McAuley and Stewart insisted, the poems had no merit, then Malley’s champions had convicted themselves of unsound judgment and corrupt taste. |

|

|

‘Ern Malley’, Sydney-Melbourne night express, 29 April 1941, Sun Photo Archive. The authenticity of this photograph cannot be guaranteed by Jacket magazine. It may be of the actor Iain Gardiner, from David Perry’s film ‘The Refracting Glasses’, 1992. Photograph copyright © David Perry 1992, 1997. Ern Malley has always had an honored place among the poets of the New York School. Kenneth Koch printed two Malley poems, ‘Boult to Marina’ and ‘Sybilline,’ in the ‘collaborations’ issue of Locus Solus, the avant-garde literary magazine, in 1961. At Columbia University in 1968, Koch introduced his writing students to Malley’s poetry, suggesting that the hoaxer’s antics were well worth imitating not for purposes of polemic but for legitimate poetic ends. In 1976 John Ashbery asked his MFA students at Brooklyn College to compare Malley’s ‘Sweet William’ to one of Geoffrey Hill’s Mercian Hymns. Which did they think was the genuine article? (The students were divided.) Ashbery’s point — and it seems to be Malley’s point — is that intentions may be irrelevant to results, that genuineness in literature may not depend on authorial sincerity, and that our ideas about good and bad, real and fake, are, or ought to be, in flux. |

| |

|

Cover of the Autumn 1944 issue of Angry Penguins; cover art by Sidney Nolan. The art relates to the quoted matter (cover, bottom right) from the poem "Petit Testament", below, as follows: |

|

Crazy as it seems, the Malley poems do have merit. In a poem written during the second World War the French poet Robert Desnos pictures himself as ‘the shadow among shadows’ poised to ‘enter and reenter your sunny life.’ This is Malley’s self-conception, too. His gallows humor, self-lacerating irony, and odd arresting juxtapositions contribute to an effect that other poets of the period strove for but few attained so unerringly as this speaker of ‘No-Man’s-language appropriate / Only to No-Man’s-Land.’ |

|

| |

David Lehman is a poet and critic, and the series

editor of the annual anthology The Best American Poetry. He

divides his time between Ithaca, N.Y., and New York City. |

|

Jacket 17 — June 2002

Contents page This material is copyright © David Lehman 2002 and Jacket magazine 2002 |