|

This is Jacket 12, July 2000 | # 12 Contents | Homepage | Catalog | |

Tony Bakeron Basil Bunting |

|

Basil Bunting, Complete Poems, ed. Richard Caddel, Bloodaxe, Newcastle, UK, 2000.

Basil Bunting reads Briggflatts & other poems, a two-hour double cassette, also from Bloodaxe.

Basil Bunting on Poetry, ed. Peter Makin, John Hopkins, Baltimore & London, 2000.

|

|

THE CAREER of Basil Bunting, who would have been one hundred this year, is now sufficiently well-known that it hardly needs repeating: co-dedicatee in 1934 with Louis Zukofsky of Pound’s Guide to Kulchur, he remained a ‘struggler in the wilderness’ until his mid-sixties when the publication of Briggflatts, his last substantial poetic work, brought belated critical recognition of his centrality to any version of Modernism in the literature of Britain in the twentieth century. |

|

His craft at root derives from that simple motive: to communicate, to please, with patterns of sound. Readers can try to build whatever edifice they like on this foundation, but they would misread Bunting if they ignore it. Fortunately we don’t have to. A reader who hesitates to follow Bunting’s advice to the letter — read aloud — has now two cassettes of him reading his own work easily available, plus the texts of a series of lectures he gave at Newcastle between 1969 and 1974 in which he reveals how his own reading in the history of English poetry is an extraordinary hearing of verse. The main argument can be sketched quickly. Bunting assumes that art is shape, not content. There is no excuse, of course, for decoration: it simply spoils shape. In this art, in the English language, rhythm is the most essential shapable: and if the poet has the rhythm right, he probably needs nothing else to give main form to his poem.... But rhythm, the whole key to English verse, Bunting says, has to be made by English means. Languages vary in their constitutions; what has force in one may have little in another; stress is the key to English, though not to French.

— and here Bunting begins to shed the load from the juggernaut that has caused so much pedagogical tarmac to be laid down in the cause of the teaching of Literature — ...This grotesque [iambic pentameter] has only heightened the English propensity for fluff, for decoration...: for the pentameter is too long and invites glittering nothings to fill it out...

— out onto the hard shoulder goes whole passages of Marlowe, Milton, Keats, and almost everything from the nineteenth century: why transport the burden of excess padding and packaging ? — The cure is, first, a return to the essential of English, which is the play of strong stresses, irrespective of overall syllable count...; second an ear for music, for music is the true parent of poetry. The flexibility and intricacy of song as a frame for words taught Wyatt and Campion to bring forth words equally varied and alive in their cadences.

So Bunting advanced Wyatt from the status of a minor poet with dubious control over his material (in 1970, Muir’s edition of the poems was still hardly canonical), to the ‘effective founder of modern English verse’ — ahead of Chaucer. ...cease to conspire

Without Wyatt and Beowulf, without having read them aloud and registered the movement physically in the voice, without having felt his mouth working round their rhythms, suppler than anything he could have taken from nineteenth century practice, Bunting’s craft would surely have been slower to develop. |

| |

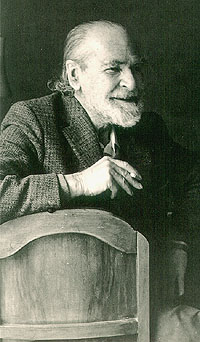

Basil Bunting, Blackfell, Washington New Town, 1982 (detail) |

|

Not that one can doubt that it would have developed anyway. The appendix to the Complete Poems prints the two pieces of juvenilia that were published in Bunting’s youth, both remarkably conventional given that Bunting knew and already admired Whitman. There seems at first to be a confusion of detail and decoration, but the balance is never lost, and the main design shows through, ultimately, without insisting on itself.... The detail intertwines and repeats, and yet the richness of the detail never obscures the balance, the beautiful balance and symmetry of the main design.... [There’s] much more to it than the hearer or beholder realises at first. [It wasn’t done] by guess; it required some pretty complex geometry, a whole system of intricately related and balanced ratios.

There isn’t a page of the Complete Poems that isn’t testimony to the same skills. Briggflatts is the example par excellence and one could spend hours unravelling its symmetries. But if the poet has spent so much effort to make a design that doesn’t ‘insist on itself’, it would be a folly and impertinence to try and do it for him. The design manifests itself when the poem’s heard. The cassettes of Bunting reading would be worth having even if it was only for his rendering of Briggflatts. They allow us to hear how his pacing of the final pages completes the aural design of the whole as decisively as any recapitulation in the sonatas of Scarlatti, selections from which Bunting intended to punctuate the poem though they were unfortunately unavailable for this recording. But one can as easily illustrate aural design in the short poems. A thrush in the syringa sings.

The design here doesn’t need spelling out though it merits some study for the play of rhyme, internal or half-rhyme and repeated vowel shapes is too subtle to take in at a glance. The point is that, like the song of the common song thrush which is distinctive for both its variety and its repetition, the sounds are structured into an intricate pattern. They determine the form. This is Bunting’s answer to the problems posed by a poet such as Spenser, who can make sounds that glitter in the ears but who too often fails to make them function structurally because he wanted them to serve, in Bunting’s view, alien rhythmic methods. ...we ask nothing |

|

Jacket 12 Contents page |