|

|

| |

| |

| |

Alex Katz:

Don't be bored | |

| |

| |

| |

The real lives of artists, and their relationships with those they consider their peers, are much more complex than the processes of art history sometimes render them. In looking at the extraordinarily rich texture of the New York art world from the early fifties until 1966 through the lens provided by Frank O'Hara, I want to suggest one alternative path through the period. | |

| |

Other focal points would yield other narratives, but the milieu that is visible in O'Hara's writing and in the work gathered for this exhibition will, I hope, be compelling enough to communicate with those who look back at it today from a distance of almost forty years. This account is devoted to the artists who made up much of his circle, among whom he was by turn acolyte, friend, model, muse, collaborator, and critic. | |

| |

It is hard to imagine a position further from that of O'Hara, who trusted only his emotional responses. The composer Morton Feldman has said that, 'It is interesting that in a circle that demanded partisanship above all, he was so totally accepted. I suppose we recognized that his wisdom came from his own 'system' - the dialectic of the heart.' [3] He never talked about his own work; at least, not to me. If ever I complimented him on something he had done he would answer, all smiles, 'well, - thank you.' That was the end of it. As if he were saying, 'Now, you don't have to congratulate me about a thing. Naturally, everything I do is first rate, but it's you who needs looking after.' [7]Such self-effacement was not simply a matter of politeness. On a deeper level O'Hara's very sense of self was constantly refracted through his relationships with other people, their work and their needs. He was always available. 'At times Frank seemed to be a priest who got into a different business,' Alex Katz wrote. 'Even on his sixth martini - second pack of cigarettes and while calling a friend, 'a bag of shit,' and roaring off into the night. Frank's business was being an active intellectual. He was out to improve our world whether we liked it or not.... The frightening amount of energy he invested in our art and our lives often made me feel like a miser.' [8]

| |

| |

what we might call 'criticism based on movement affiliation' is bound, sooner or later, to give way to a historical and literary reshuffling of the deck. Beckett the 'absurdist' becomes Beckett the Anglo-Irish heir to Yeats and Joyce. Frank O'Hara, the 'New York School Abstract Expressionist poet' becomes O'Hara, the oppositional gay American poet in the line of Whitman.' [15]As each wave of more or less facile characterizations emerges and recedes, what is left behind by such historical sifting (we hope) are the individual voices of the poets. It is precisely the specificity of O'Hara's poetry (much criticized at the time as 'gossipy' or diaristic) that gives his voice such a distinct presence today. His language always tended toward the vernacular and the casual, in marked contrast to what Kenneth Rexroth called the 'dreadful posturings' [16] of the poetry mainstream. O'Hara wanted to be able to pull his poetry right out of the life he was actually living, not cobble it together as labored allegory. 'Lord! spare us from any more Fisher kings!' he sighed. [17] Instead, as Ashbery put it, 'O'Hara grabs for the end product - the delight - and hands it over, raw and palpitating.' [18] Of all the so-called New York School poets, it is unquestionably O'Hara who had the closest relationship with the painters for whom the term New York School has now become canonical, despite differences between the work of, say, Willem de Kooning and Barnett Newman that are at least as wide as those between O'Hara and Ashbery. O'Hara wrote the first monograph on Jackson Pollock (in 1959), he was a close friend of de Kooning and Franz Kline, and he organized The Museum of Modern Art retrospective of Robert Motherwell's work in 1965. One of his simplest and most affecting poems, 'Radio,' is written in praise of a de Kooning painting he owned at one time, Summer Couch (1943, below). | |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

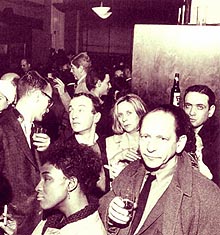

artists like de Kooning, Franz Kline, Motherwell, Pollock - were free to be free in their painting in a way that most people felt was impossible for poetry. So I think we learned a lot from them at that time, and also from composers like John Cage and Morton Feldman, but the lessons were merely an abstract truth - something like Be yourself - rather than a practical one - in other words, nobody ever thought he would scatter words over a page the way Pollock scattered his drips. [22]The work of Stéphane Mallarmé and the Dada poets notwithstanding, words always retain elements of representation. O'Hara never made any very serious attempt to pursue an experimental practice that would have taken him outside language as a referential system. He accepted that his poetry - any poetry - could never achieve the direct immediacy in itself of a brushstroke across a piece of canvas. Everything suddenly If there is a true point of contact between New York School painting and O'Hara's poetry, it is to be found less in the painters' pursuit of untrammelled access to the realms of the unconscious - O'Hara was above all self-conscious - than in the idea of the spontaneous. 'Like Pollock,' Ashbery wrote, 'O'Hara demonstrates that the act of creation and the finished creation are the same.' [23] He could produce wonderful poems in a single sitting, most famously 'Poem (Lana Turner has collapsed!),' which he wrote on the Staten Island Ferry on the way to a reading with Robert Lowell: I have been to lots of partiesHe was also capable of writing poems in bars or at parties, and often did so. Kenneth Koch vividly recalls him sitting typing in the middle of a crowded party. 'Whatever was going through his head was precious. Frank was trying to run faster than ordinary consciousness.' [24] This fecundity impressed painters who were struggling to produce. 'All the artists I knew at the time were vaguely constipated,' Goldberg recalls. 'The favorite refrain of the period was 'Ain't it hard, gee ain't it hard.' [25]

| |

| |

| |

| |

Is it dirtyThis love for the filth of the city was matched by a hostility to the country. 'I'm not a pastoral type any more,' he wrote. 'I hate the country and its bells and its photographs.' [33] The unchanging rhythm of church bells and the frozen passage into the past of old photographs form an unwelcome counterpart to the ever-changing clamor of the city, the constantly evolving present in which O'Hara wants to live. The city can even be seen as the new nature, superseding the old rather than simply obliterating it. 'A woman stepping off a bus may afford a greater insight into nature than the hills outside Rome, for nature has not stood still since Shelley's day.' [34] He welcomed the changing fabric of the city, the construction workers continually transforming the urban landscape. His friend William Weaver was with him one day as some old brownstones were being demolished. I said, in the usual clichéd way, 'Oh what a pity they're tearing down those brownstones.' Frank said, 'Oh no, that's the way New York is. You have to just keep tearing it down and building it up.' [35]O'Hara's new nature is a kaleidoscope of individual moments that flow into and out of his consciousness, and his New York is both grimy and glamorous. It's my lunch hour, so I goIn the evening there were cocktail parties and dinners. Jane Freilicher's Early New York Evening (1953-54) shows us the view from her studio as the sun starts to go down over the city. O'Hara was a constant presence here, and this downtown view gives us the dirty but alluring city he loved. In a moving 'Poem Read at Joan Mitchell's' (1957), but addressed to Freilicher on the occasion of her marriage, O'Hara called up the city they all shared: Tonight you probably walked over here from Bethune StreetThis kind of evocation, verging on invocation, demonstrates the perfect pitch for the telling detail that O'Hara brought to his walks down the streets of the city. 'Attention was Frank's gift and his requirement,' Bill Berkson wrote. 'You might say it was his message.' [38] But his attention was not simply a matter of close observation. The details are always acutely personal, specific to particular individuals, in this case Jane Freilicher. If Freilicher's Early New York Evening evokes a moment of calm before the evening begins and before O'Hara had risen to real prominence, Howard Kanovitz's The New Yorkers (1967) shows us O'Hara in full flight, an urbane sophisticate exulting in brilliant conversation. O'Hara's poetry begins in the middle of real lives, casually dropping names as it they were as familiar to the reader as to the poet. While the informality of the tone can at first seem baffling, as a reader one is quickly drawn into O'Hara's world, access to which is surprisingly easy to obtain. He simply assumes that people will be interested enough to find their way in, as he himself had quickly found his way into the worlds of avant-garde painting and poetry after he came to New York. The invitation is open for those who care to accept it. O'Hara is confident that it will be taken up. Barbara Guest remembers being in Paris with O'Hara in the summer of 1960. She had identified the location of the 'bateau-lavoir' building where Picasso and many other artists had had their studios in the early years of the century. But O'Hara didn't care; he wouldn't even go inside. 'Barbara,' he said, 'that was their history and it doesn't interest me. What does interest me is ours, and we're making it now.' [39]

| |

| |

It is 12:20 in New York a FridayAt any moment, the whole world that surrounds him and through which he moves can suddenly come into the sharpest focus, and it is necessary to be absolutely in that moment. At lunchtime in midtown Manhattan on a hot summer day, 'Everything | suddenly honks: it is 12:40 of | a Thursday.' [42] Such intensity of living always carries with it the fear, actually the certain knowledge, that at any moment it could all come to an end, and this too is part of what drives O'Hara's writing. There's nothing more beautifulUntil it is over, life is to be lived with style, but also with an intense emotional commitment to each moment as it passes.  John Button's portrait of the dancer Vincent Warren, with whom O'Hara had a passionate affair, shows him stretched upward in a pose that can be held only briefly. It is a perfectly balanced visual representation of an image that will inevitably pass away in another second or two, but which approaches perfection while it lasts. Its very ephemerality makes it all the more urgent to grasp. Its counterpart is Button's portrait of O'Hara diving into a wave. The tension is resolved, as the poet flies headlong into the ever-changing crest of the present. John Button's portrait of the dancer Vincent Warren, with whom O'Hara had a passionate affair, shows him stretched upward in a pose that can be held only briefly. It is a perfectly balanced visual representation of an image that will inevitably pass away in another second or two, but which approaches perfection while it lasts. Its very ephemerality makes it all the more urgent to grasp. Its counterpart is Button's portrait of O'Hara diving into a wave. The tension is resolved, as the poet flies headlong into the ever-changing crest of the present.(above) John Button - Swimmer, 1956, detail | |

| |

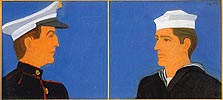

C R E D I T S © Alex Katz / Licenced by VAGA, New York, courtesy Robert Miller Gallery - Frank O'Hara, 1959-60, front and back view of cutout figure; painting Marine and Sailor © Camilla McGrath, Courtesy Earl McGrath Gallery - photo of Larry Rivers and John Ashbery at Frank O'Hara's funeral, Springs, Long Island, 1966 © George Cserna - Frank O'Hara (wearing bow tie) with Elaine de Kooning and Reuben Nakian at the Nakian opening, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1966 © Eric Pollitzer, New York, courtesy Allan Stone Gallery - Willem de Kooning, painting, Summer Couch © Brian Forrest - Michael Goldberg and Frank O'Hara, cover of Odes, 1960 © Larry Rivers / licensed by VAGA, New York, lithograph: Stones: Inner Folder, 1957-60 © Al Leslie - still from USA Poetry: Frank O'Hara, 1966 © Fred W. McDarrah - photo - Closing of the Cedar Bar, March 30, 1963, detail © John Button - Swimmer, 1956 (Frank O'Hara diving into a wave) | |

|

|

|