|

Pagan Kennedy

in conversation with Noel King

|

|

|

Pagan Kennedy was interviewed in Tufnell Park, London

This piece is 4,600 words or about ten printed pages long

|

|

|

Noel King: Could we start by getting some information on where you live in Boston, and how you wound up there?

Pagan Kennedy: I live in Somerville, a rock and roll, Vietnamese, student neighbourhood part of Boston, and I was born in Maryland. I'm 33, single, no kids. I went to Wesleyan where I studied American Studies which was great because it got me started on popular culture. And I went to grad school at Johns Hopkins where I got an MA in Fiction and I studied with John Barth and that was really good. Pagan Kennedy: I live in Somerville, a rock and roll, Vietnamese, student neighbourhood part of Boston, and I was born in Maryland. I'm 33, single, no kids. I went to Wesleyan where I studied American Studies which was great because it got me started on popular culture. And I went to grad school at Johns Hopkins where I got an MA in Fiction and I studied with John Barth and that was really good.

I lived in New York for a couple of years but I didn't like it very much. I liked parts of it but I didn't like the way everyone was so career-orientated. I really liked the Boston scene because it was people doing things because they were fun, and when I moved up to Boston it was just the beginning of the 'zine scene, so I just fell into that, then went to grad school.

|

|

|

Noel King: Which part of your writing came first? Was it the popular culture criticism that St Martin's Press have put out, or the fiction writing that found its way into Village Voice Literary Supplement and then on to Serpent's Tail Press? Or were you doing both things at the same time?

Pagan Kennedy: I always do lots of things at the same time. I was interested in being an arts journalist because I thought that was the most practical career choice I could come up with out of school [ie after finishing University] so I started working as a general, low-slave type at the Village Voice. I was doing journalism at the same time as I started doing stories. I studied with Gordon Lish who was a big guy in the 80s fiction world, and I kind of got a start from that because he really liked my work, and I was young and that was a big thing for him. I got my first story accepted when I was 22 and that made me more serious about fiction writing, it made me think I could really do it. My first piece was part of a novel that didn't see the light of day. It eventually died, but a piece of it was published in connection with Lish. And he then published some of my stuff in The Quarterly.

But once I moved out of New York, I seemed to be off his A-list. You know, it was sort of, "if you can't live in New York, you can't be serious about being a writer." But he was wonderful to give me a start, and then the Voice was wonderful to me. The head of the VLS, M.Mark, said I could do whatever I wanted for them. I'd sent in, through someone I knew, the story on Elvis that is the first story in Stripping. So much stuff comes in there, you'd never expect to get read, but knowing someone helped.

And then M.Mark was so generous, she gave me a lot of room to make mistakes, and I did make mistakes because I was very young. She gave me a lot of room to do what I wanted, I did a column on 'zines for them, anything I wanted, however marginally connected to literature, I'd just do whatever I happened to be interested in.

Then, after grad school, such an intense writing programme, I was burnt out, and very sick of agonising over the perfect word, and I loved the 'zine culture because there was such a feeling of, write it off in a hurry, illustrate it yourself, lay it out yourself, then take it to a Xerox shop where you have friends, so they'll do it, print it, for free and you'll have it out in two days, and there it is! That was freeing, though I resisted it by thinking, "I'm a professional writer." But all my friends were doing 'zines in the late 80s, there were tons of them, and so I started doing one just for fun.

And the minute I started doing one it just came out as if it had been in there for a long time and it was about all things I couldn't write about in my fiction, about my life, being a marginal person, things about my friends, and I could do drawings and cartoons, all the things you couldn't incorporate into your fiction.

Noel King: You've said that you drifted into fiction writing because it was the closest thing to what you wanted to do, which wasn't necessarily to write fiction.

Pagan Kennedy: I don't think it would ever have occurred to me to write a novel unless it already existed as a form. It's a weird thing to write 200 pages about people you've made up. I felt under a lot of pressure at that time to write a novel, I would have done anything to get away from copy-editing, which is what I was doing, actually it was even worse because I was copy-editing computer articles. I loved the people I worked for - P C Week. They let me wear whatever I wanted, stay wherever I wanted, behave however I wanted, so long as I got my work done. I wanted to get out of that, and maybe into teaching, but that seemed to require a novel rather than just stories. You couldn't be a career writer and just do stories.

So I was trying to do a novel and it seemed a very weird form. After I left grad school in 1988 I started Spinsters and I was working on it, turning it around in all sorts of different ways, and I started my ''zine at that time. So I was travelling parallel courses, one was trying to do what other people have done really well, trying to learn from what they've done, and fit into that literary mould, and at the same time discovering the 'zine form and saying what do I want to do with it? It was a very liberating feeling to think that I could do whatever I wanted. So I had the two opposite ends of the writing spectrum happening at the same time.

Noel King: Stripping came out in 1994.

Pagan Kennedy: I'd pretty written most of those stories when I was 22 to 24. I wrote the title story in 1990 or so and I look at that collection now and wince a little because I see my development as a writer. 'Stripping,' the final story I wrote for that, is much stronger than the others.

Noel King: What persists across your collection of stories and into Spinsters, is the idea of a self that is many in one: you treat the issue of madness; a child lies to parents in 'The Tunnel'; the girl in camp plays with the idea of aspects of a self, while Spinsters can be seen as Frannie's coming out or a kind of make-over story.

|

|

|

Pagan Kennedy: You've definitely hit on one of my obsessions and I think it's a very American obsession, with all the self-help books and so on. I've always been interested in the question of 'what is the self', tracing it back to Ben Franklin's idea that the self was a little machine that you could programme; there was no mystery or anything, you could make it be anything. He had his programme of moral perfection with its chart of days of the week on one axis, and sins on the other, and he'd black in when he'd had a sin. Of course he's probably lying about most of it but his idea is that he'll eventually get fewer and fewer black marks and be perfect! Pagan Kennedy: You've definitely hit on one of my obsessions and I think it's a very American obsession, with all the self-help books and so on. I've always been interested in the question of 'what is the self', tracing it back to Ben Franklin's idea that the self was a little machine that you could programme; there was no mystery or anything, you could make it be anything. He had his programme of moral perfection with its chart of days of the week on one axis, and sins on the other, and he'd black in when he'd had a sin. Of course he's probably lying about most of it but his idea is that he'll eventually get fewer and fewer black marks and be perfect!

That idea seems to me very American and persists in the self-help books we have now, the idea that you can decide to be whomever you want to be, you can systematically reprogramme yourself, that's something I'm very interested in. I think I'm all too prone to doing things like that, going off on those Franklin projects. You know, like this summer I'm going to work out and have huge muscles, this winter I'm going to read all the great books. I'd have all these projects but again and again confront the fact that there is mystery there. But in my 'zine, Pagan's Head, that was something I was able to explore a lot: it was about me but me as a literary or comic-book character. I had this whole persona of being the queen of Allston, riding around on my little bike being fabulous, but it was all a joke. And it had a certain tone that developed, and my friends would say, "this thing happened and it's very Pagan's Head," or they'd want to write about it. So my friends got into the act of this sort of parallel world, this work of literature that was also our lives. And people would read the zine and think I was that person, so I could play with that.

The publishers made me write essays when I did the 'zine book and something I wrote a lot about was struggling against the fact that I had created this persona for myself and then it became a little bit psychotic. The publishers made me write essays when I did the 'zine book and something I wrote a lot about was struggling against the fact that I had created this persona for myself and then it became a little bit psychotic.

So I'm really interested in characters who are aware of the possibility of being all these selves but that you have to make up a story for yourself such that your life is the story you choose to make up. So in the story 'Stripping' the woman is raped as a child and she could have accepted this tragic identity, but she decides that she was this wild girl and she wanted it all to happen. So a lot of my characters could choose to be a sad story but they twist it around in a way to save their lives.

A friend of mine is a therapist and she tells me that a similar thing is going on in mainstream therapy where a lot of therapists, instead of using one model for all their patients, will look at the patient and say, this person needs a feminist model, or a Freudian model. And so they try to help their patient come up with a story of their lives that is redeeming. And she believes that people can live through any kind of hell so long as there is a meaning there; then it becomes bearable. If you have a story that you can live by then you can make it through anything.

Noel King: In Stripping it is possible to see a close fit between fictive events and the urban hipster who has written the book. With Spinsters, it's harder to find a close relation between you as the living writer and these characters who travel around the States in 1968. How did you research this topic and what amount of play are you having with these temporalities - then and now - whereby two mid 30s New England spinsters go on the road in the year of Paris riots, the Prague spring and all the turmoil in the US?

|

|

|

Pagan Kennedy: Well, I worked on the book for years and years, and stopped for a long time. I started it when I was 28 and those characters were much older than I was, their childhood was in the 1940s, and it was set in 1968, so I had to do a lot of research. The characters just sort of came to me.

I have two sides to my writing, one is the urban hipster sort of life I'm involved in and the other is this baroque southern side of my family.

My grandmother is one of the main inspirations for my storytelling. She's a font of family stories, she grew up on a plantation where there was a spinster living in an attic and there were lots of other spinsters around. They lost all their money but I saw the plantation when I was a little kid. It's in Roenoake, and my grandma has this breathy Virginia tidewater accent and tells a typically baroque Southern story of how grand we were. I always heard the Civil War referred to as "the war between States."

Noel King: "The war of Northern invasion."

Pagan Kennedy: Yeah! The "war of Northern aggression" and I grew up with this tragic, doomed history, stories of how great we would have been if the South had actually won. I had relatives who were in the Confederate Government and one guy was always referred to as the "treasurer of the Confederate Government." Later I read about him and discovered he was the receiver of abducted property! So the guy was going around and taking whatever they could steal from the North.

But everything got a little softened in the stories, and I grew up with that and I think that's another aspect to the idea of storytelling and its role in peoples' lives. The South being a culture in defeat meant that the only thing you had were your stories and you could gussy everything up and stress all the eminent people in the background and overlook the village idiots.

When we went to England as a kid we went to Bath for a family re-union of the Tuckers. St. George Tucker was probably a horrible man who supported slave-holding but we came up for a family re-union. So a lot of my childhood involved traipsing around and hearing of the glory that was. And so another side of storytelling I adopted involved baroque stories of a doomed world, a desperate nostalgia for a past that you didn't even live through. A lot of my grandmother's stories had been handed down, concerning a time she hadn't experienced. The stories were of glory days while she grew up in desperate poverty on a plantation where they refused to sell off the family furniture!

So that was one place Spinsters came out of. And then I sort of pushed that on to Easy Rider and the American road myth. I knew in the 60s you could be a spinster after 30, so that was the origin of the book and although I meant them to have grown up in New England, people I've met refer to them as the "Southern ladies" so obviously the Southern voice was in there, I couldn't expunge it. I wanted to use these myths and I thought if you have spinsters then you must have a father who they doted on who's just died. So I tried to take what I felt was the myth, and I thought the father would have had lung cancer, and then my father was diagnosed with lung cancer. So it became the opposite of an autobiographical novel and that put me off the book for a long time, while my father was dying and I was dealing with that. And then I guess I came back to it after two years with a lot more depth, and I rewrote it and rewrote it because I was really learning how to write a novel.

Noel King: What aspects were concerning you in the rewrite: was it to do with plot, character, narrative voice?

Pagan Kennedy: In the beginning I had tried to make it a very plot oriented book and to have stuff happen, events, because I was very ambitious to do that sort of book. I admire books that are driven by plot but it just didn't work. I had made my main character much more prudish in the beginning so it always felt like I was fighting against her, taking her by the shoulders and saying "you go over here now! Do that! Do this!" I felt like I was at war with my main character, so I did two things.

One was to make the book character-driven; I respected my main character and gave her her head, and also made her someone who wanted to experience life more fully instead of wanting to shut things out, so that the changes she goes through seem more natural. I took out a lot of the plot stuff and really tried to follow what she wanted to do, so that the things that happened seemed natural in relation to her. In a way it was an exercise in giving up my ego, because I was ambitious to write a certain kind of book which showed off certain technical skills. So I had to sort of say to the main character, "you do what you want and I'll transcribe it, and if I don't achieve this certain effect I want, that's fine."

Noel King: You've said you now regard yourself as a stronger writer than you were earlier. Could you say something about how and where you locate that strength, what can you do now that you couldn't do before, or couldn't do as well?

Pagan Kennedy: A lot of my stories aren't autobiographical. Some of them have things that happened but I changed it around a lot. Although they're not strictly speaking autobiographical, they are based on things I was involved in . . .

Take the example of the Elvis story, in Stripping; I did go to Graceland with a boyfriend. As I get stronger as a writer I depend less and less on any of my experiences. In Spinsters there's nothing really in common with my life. And now I think I can do more characters, for example, male voices, in a way that feels very natural whereas I couldn't bring it off before. So my range is getting broader and I can think in bigger swatches of stuff.

I don't get obsessed so much now with sentences and words. I've let a little of the 'zine aesthetic creep into my fiction; I'm not a perfectionist, I get to a certain point and I have to go on, I can't sit there tinkering.

Noel King: The 60s is such a mythologised decade, how did you set about researching it?

Pagan Kennedy: I did a lot of reading. I relied heavily on William Manchester's The Power and the Glory. I had to research things like what cigarettes they'd be smoking, and with rationing during the war, what would you have and not have. And the father as a conscientious objector.

Noel King: I was very struck by the section in Spinsters which discusses the girls' father's status as a WW2 conscientious objector; how the mother represents the government's act of torture - the year-long enforced diet of salt water and emergency rations that induces delirium and hallucinations - to the two daughters as their father having volunteered for a medical experiment. And the father discovering after the war that the Navy already had found a way to treat salt water so that it could be drunk safely. Where did you get that idea?

|

|

|

Pagan Kennedy: That was true. They did do things like that, and there were two men who had to drink sea water, and that was a kind of poetic detail that I picked up on. There's very little writing about the conscientious objectors during WW2 so I really had to search for that material. I was interested in the moral problem of being a conscientious objector. So I did a lot of research but in my final rewrite I kind of let go of that research, let go of being factually accurate, and freed myself. There's a whole riff on the mutascopes which is more fantastical than factual.

Noel King: When you send them on the road were you very particular about where they went, their itinerary?

|

|

|

Pagan Kennedy: I wanted the South because I stayed with relatives in Norfolk, Virginia and as a kid there was this whole thing of weird decrepit old women living in old houses, and I loved that setting. Did I change that to Richmond? I frittered around with the itinerary a bunch and I wanted them to wind up at the Grand Canyon. It's weird with the film Thelma and Louise coming out around the same time and ending at the Grand Canyon. I really think there are these patterns and the thing is to try to follow them and twist them. It's the same fairytale but told different ways.

Noel King: What is your writing regimen?

Pagan Kennedy: I'm still doing the 'zine books and I do a lot of media stuff now. I used to be very very compulsive and a lot of writers I've talked to say a similar thing. But you learn to trust it, to trust that it's not going to go away just because you didn't write today or didn't write for a week: it's not like your talent or skill is just going to vanish and it's nice to be able to trust that, to trust that it'll come back.

Also if writing's not going well I do other things, like cartoons, drawing a layout, or photographs. I find writing fiction is the hardest and I try to get as much done in the morning as I can because I lose it in the afternoon. I like having other people around. My boyfriend has his office in my apartment. Friends come over or I go to their place. I organise writers retreats where we write all day and then read it to each other.

I guess there's a stereotype of the writer as an isolated person but for me, my community is too close to my heart, the people who've helped me. I don't think I've done this alone at all. I've had a writer's group for ten years and people have floated in and out of that. We come up with whole scenes for one another, we get into each other's books. There are pieces of other peoples' books that I've come up with and other people have come up with pieces of my book.

Noel King: Why Boston?

|

|

|

Pagan Kennedy: I was unhappy in New York. There is a huge music and band scene in Boston and a huge writers' scene as well.

Noel King: What writers have been important to you over the years?

Pagan Kennedy: As a younger writer I really loved Nabokov as a stylist and a storyteller. I used to look at those sentences and admire them. I went through a big Nabokov phase. Pnin is my favourite, it's so heavenly and so tragic in this beautiful way. Alice Munroe's stories - the writers I know agree that she's far and away the best story writer living today, what she's able to do, the frames within frames, is incredible.

An inspiration for one was Alice Walker's story about Elvis, "1955": it was very freeing to read that story and realise you could write a story about Elvis and blues singers, as your subject matter, instead of yuppies getting divorces in Westchester, which was what The New Yorker used to always publish. But their fiction is lots better now. And I love Henry Louis Gates' essays.

Noel King: He did "Thirteen ways of looking at a black man" for The New Yorker.

Pagan Kennedy: And he probably had to hand it in two days after the OJ verdict! It was amazing. I think a big emerging form is the "personal essay" or memoir, almost replacing the novel. Gates is wonderful at that. Jill Conway too, Lucy Greeley's Autobiography of a Face is wonderful. There's lots of writers' panels in Boston and I love to go to them. I saw Eldrige Cleaver's wife Kathleen Cleaver. She's a lawyer, teaches at Emory and she's writing a memoir and she's done all sorts of things. She was talking about the Black Panthers and all the in-groups and it was the first time I felt I really understood it. She gave it to you in a really cogent way, free of the rhetoric. Her memoir is of the time they were in Algeria after they'd been kicked out of the US. So it seems like anybody who's anybody is doing a memoir.

Noel King: You taught writing at Boston College. Did you find that helped your writing, or took you away from it?

|

|

|

Pagan Kennedy: The main controversy people talk about when they talk about teaching creative writing is whether it can be taught. I'm very much a believer in the idea that it can be taught, I'm just not sure that I'm the one to do it! It's very hard, very draining to do it, and when I was studying with Lish, the class was hierarchised and made competitive: you have talent, you have less talent, and so on.

I find that writing, for me, is a process of working with people in a way that isn't competitive, and that other stuff is very poisonous, always gauging yourself against someone else that you're in the same room with. I think it's okay to be competitive with your favourite writer, and try to steal their technical tricks, learn their lessons. But to compete against people who are right there around you is ridiculous.

So I very much work with my students by not saying anyone is better, and trying to get them to help each other out, so that they experience writing as working inside of each other's work: they edit and discuss each other's work. I don't do the standard workshop thing where you talk about the work as finished and you debate whether you should change this paragraph or this word. I don't like that because it's not how I work with other writers. My writer's group has as its main cause the fact that we are violently against xeroxing because you get too nit-picky. We prefer to talk about the work as being in rough draft, in transition, and we're all coming up with ideas. I try to get my students to think of writing as in process, fluid, and to think of it as a situation in which someone else might say, "I'd like to hear more about this thing you brought up."

I think a successful writing class is where I get it going like a good party or something, where there's a good feeling of people enjoying each other, enjoying being together and being really happy at the end of the year when someone reads aloud something that has become very good. So they have a joy in each other's progress: that's what's really wonderful. Anyone can write if they're not brain dead, and I think it's really dangerous to put labels on people, "this person can write, this person can't." Anybody can get better at writing, it's just like learning an instrument. Maybe the steps are less clear than when you're learning the piano but I can go through and teach people tricks, and it works with most people so long as they work hard enough.

I've worked a lot with kids, sometimes the jocks or whatever, who aren't very interested in writing. They'd write horrible, incoherent things, full of abstract words. And I'd say to them, "OK, write me a piece with no ideas. I'll get very mad if you put any ideas in there. Write about something that happened to you." And I'll talk with them until we find something they're interested in, and they'll tell me the story and I'll say, write that down. And then I go back and say, "hey, look, there are ideas here actually but they're embedded in what you're saying." And then they've understood that ideas aren't there free floating things divorced from their lives. And it's great when you get people who've never been articulate, never been able to write, suddenly able to express this thing.

Noel King: How were you contacted in relation to your nomination for the Orange Prize award?

|

|

|

Pagan Kennedy: I got some call at 7 in the morning. It's Brits calling about some literary prize; and then they told me it wasn't some pokey little prize, it was worth 30,000 pounds! So that got me awake! When I found out the names of the other nominees I was very excited to be in that company. I'm a great admirer of Ann Tyler. I'd gone through her books, saying, "how does she make them so darn readable, what can I steal here!" I've really examined her stuff for her tricks. I had no hopes of winning at all; just to be nominated was prize enough.

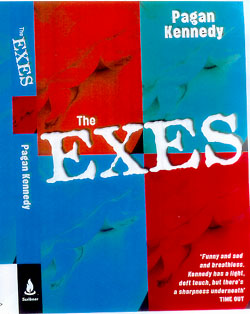

Noel King: Your most recent novel, The Exes, tells the story of four ex-lovers (Hank, Lilly, Shaz, and Walt) who form a Boston indie rock band. Each has a long chapter to tell her-his story, and Richard (Slackers, Dazed and Confused) Linklater has optioned the book. What are you working on at the moment?

Pagan Kennedy: I'm doing a non-fiction book for Viking Press, about a black American missionary who went to the Belgian Congo at the turn of the century and found his way into a forbidden city where he was "recognized" as the reincarnation of their king. It's such a fabulous story; a huge task, but I'm enjoying every moment.

|

|

J A C K E T # 8

Contents page

Select other issues of the magazine from the | Jacket catalog |

Other links: | top | homepage | bookstores | literary links | internet design |

Copyright Notice - Please respect the fact that this material is copyright. It is made available here without charge for personal use only. It may not be stored, displayed, published, reproduced, or used for any other purpose | about Jacket |

This material is copyright © Noel King, Pagan Kennedy and Jacket magazine 1999

The URL address of this page is

http://jacketmagazine.com/08/king-iv-kenn.html

|

|

|