|

Jack came over routinely and I was routinely sent off to the library to find out stuff. I spent the time finding it out and watching the Chinese high-school girls at the North Beach library copying the encyclopedia and giggling. Perhaps Fran learned a lot about Art History. But I always noticed, when I got back, that Jack had been trying to talk Fran into doing a lot of odd stuff. He wanted her to make junk sculpture. He wanted her to make chalk drawings on shirt-cardboards which came back from the laundry. (Fran said we didn't send shirts to the laundry; Jack offered to bring over his.) Finally he talked her into building a monument to Sad Sam Jones, the great Giant pitcher, sometimes called Toothpick Sam Jones, which she naturally had to make out of toothpicks. It was ordered as part of the course like a final exam, and so Fran had to do it. Jack took it home and put it on his ice-box, and so the course was over.

Here follow several hundred pages of Fran's life with Jack Spicer - putting out J magazine with him, pushing Heads Of The Town thru at the printers for him. Can't you make him wash his hands first? the printer asked Fran when Jack was doing crayola drawings on the flyleaves of the expensive editions.

I don't know exactly how Jack got onto the sports business. Pinball didn't work and shirt-cardboards didn't work and Heads Of The Town was over and anyway a one-time shot, and typing up magazines and washing your hands have to do with the visible. It was Sad Sam, probably. With sports, it was all there. We did go to ball games. We listened to and watched others. We had favorites. We had theories. Sports were routine - they began on a certain day according to season, started on the nose, lasted a certain number of minutes or the same number of innings every time, barring interfering accidents which were also OK as long as they remained either pure accident or could be attributed to a fix. You could count on them.

There was also Heurtibise, the messenger of Heads Of The Town, who turned up in the form of Jim Heurtibise, an Okie who won the Indianapolis 500 that year. There was the coincidence that my friend Dave Pass subscribed to Sports Illustrated and gave me back copies and we could count on them regularly. However it was, one night when Jack came over to drink hot buttered rum to start off his evening (and end ours) Fran had this big collage to show him. It was called Collage for Jimmy Brown, and was made from Sports Illustrated.

Such an act is usually called digging your own grave. But you ought to see Fran sitting in our living room surrounded by photos and colored papers of all sorts and glue, scissors, pencils, pens, paint and tile ghosts of whoever wanted in there. Open to it - Jack came over in person on his off-night to see. He was jubilant. It was straightway established that Fran would produce a finished collage every week on Jack's night, made out of SI photos primarily, and that it would be a battle of the worlds at the same time (of father-daughter, teacher-student, the worlds, that is). I was happy about it: I figured we would have a history of the sporting world for that year.

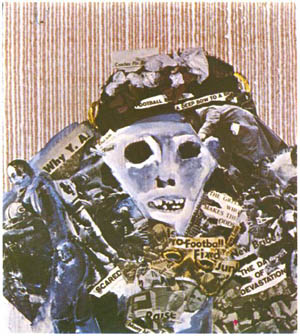

Collage for Jimmy Brown

We called him Jimmy in those days. It was a big year for him. Something bothered me about it, though, and later on I figured out what it was. The main photo . . . ain't of Jimmy Brown at all. It is Ernie Davis. Ernie was another Syracuse running back, and by the time Jimmy Brown got famous for throwing girls out of motel windows and was going to become a movie star, Ernie was dead of leukemia. Please note that time is a bit skewed here. I hope that isn't a sign of anything. When I announced my mundane discovery, Fran and Jack were delighted. It proved they were on the right track. . . .

King Football, 24 by 27 inches

Did someone mention the fact of the word "Jim" occurring over and over again in Jack's work? Now "the things that are for Jim come to an end," it goes on, not ending. That "Jim" isn't me at all. It isn't even Jim Alexander a lot; it ain't Jimmy Brown or Jim Heurtibise either, although it's some of the latter three. It's a name. Just imagine you write "Jim" over and over again and in the end it turns out to be "Ernie". That's just the kind of thing that pleased them two voyageurs . . . you get a hint of the notion, the terms of war . . .

King Football showed up next week. It wasn't done when Jack showed up, so he got to sit down on the floor in the midst of all Fran's Sports Illustrated photos and her Japanese and French fancy papers and pick up things and lay them down and get everything mixed up and talk about what ought to go in to finish the collage. (My own job was to make hot-buttered-rums and shut up. I did, since it was in my own interest.) Since it wasn't done, you can see whose things are whose, if you want to. Fran had made the skull-face, on top of the mountain of images. She had pasted Scared, Football Deaths. Her images, painted or pasted, are of players. Some of them kid-players, sitting on benches, trudging back to benches. The Day of Devastation is there. In short, it is not a picture about football players. Playing, they ain't.

Why Y.A.? is there. Did Jack put that in, or did Fran already have it? I don't know - they kept meeting at places I never foresaw - but Fran loved Y.A. Tittle and he had just been traded by the 49ers for Lou Cordelione, who was never seen or heard of again.

Trading Y.A. Tittle, the Bald Eagle! Did Fran think that had something to do with the image of death? Jack thought it had plenty to do with it, and so you start getting Raise (the 49ers were threatening to strike) and Bribery ([Jimmy] the Greek is there again, left over from last week) . . . we have got right into Jack's mythology, which says that if Tittle was traded it meant either that the leagues were fixed (it was the N.Y. Giants turn to win) or that the 49er management just wanted a million dollars, and both meant the death of the game.

Is Pro Football Fixed? right over the Halloween mask. Under it, Junk. Perhaps that was the beginning of Jack's obsession with the fix - we'd go to the ball game and an outfielder would drop a fly ball and Jack would claim he saw Horace Stoneham signalling the outfielder to drop it from a secret place in the stands. The game was fixed, all the games were finally fixed, the owners were pushers, the players fixed, scared, dying, the games dead, the fans were zombies.

If Jack or anyone was around while Fran was working, she'd always have to ask them for advice or suggestions, but after they began to suggest things or put in stuff, she would begin to get mad. So, here, she took the collage away from Jack and finished it off with a crown of crepe-paper flowers of purple and white which seemed to fade almost as soon as they were pasted on. They made Jack's notions less, by including them in an overpowering Mexican-Halloween dirge, a Dance of Death, reclaiming it all for what she had meant in the first place.

Jack made a final effort, wanting the collage to be called King of the Mountain, that being the only childhood game I ever heard him mention. His game, of course, his image of lost youth, along with trap-door spiders in vacant lots. Fran had intended to call it A Deep Bow To A Big. It got called King Football.

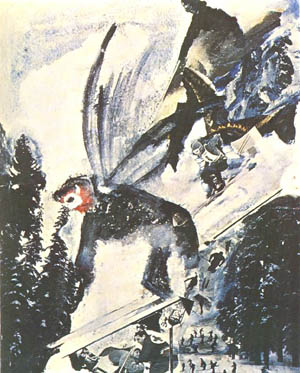

Blackbird, 24 by 27 inches

It's now the dead season of sports. Football over, spring training not yet begun. We were all conservatives - football, baseball, college basketball, those were the only sports, the rest being merely exhibitions.

Sports magazines publish all year around, though, and so you begin to see stories and pictures of fishing, track, safaris, skiing, auto-racing, hockey, horse-racing, even bridge games.

Fran used these four weeks (I think) to work on making collages, make beautiful collages, establish how she was going to go about making them - by implication, before Jack woke up and got in there again. A hint of terror in Blackbirds, perhaps. Images - open mouths, Wilt's open mouth, bassmouths (Jack did manage to slip in that toothbrush, but it's just there, not hurting anyone). For these are all Fran's images, her birds, her plants, water, skies, and wings. . . .

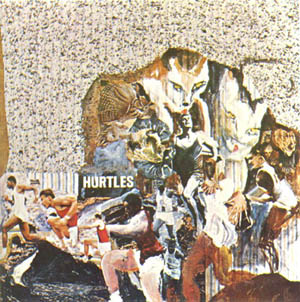

Hurtles, 24 1/4 x 24 1/2 inches

It's completely Fran's invisible world in Hurtles. The dark woods on either side of country roads at night, woods full of owls and the yellow eyes of cat-like animals. Out of there the great Australian runner comes flying, another man with a secret training regime given him by an old wise man, bursting into a crowd of runners all going like hell was after them. Probably hell is after them, since it don't look like they are just running for the fun of it, but they are getting out of there, and it doesn't look like anybody or anything is going to catch them. . . .

6

It is, after all, as on-looker and pedant that I write.

. . . as if made to show me the process of teaching and of making art. The procession of them, as they are inseparable. "The clarification of this process," writes Confucius, "(the understanding or making intelligible of the process), is called education."

Fran sees no reason for, and is annoyed by, this.

Confucius? Oh, says Jack, you must mean Eddie Confucius of the old St. Louis Browns. The one who got shot by a lady-fan in a Detroit hotel room.

7

The series never made it to baseball season. Naturally, since baseball was the only sport any of us cared about . . . .

"I am tired of the efforts of the invisible world to become visible," Jack wrote later. But he wasn't. Or perhaps he was - he kept on courting it, but that doesn't have to mean he liked it. In any case, he turned into a hero, which he couldn't stand. Fran said that everything that ever happened to Jack always astonished him, even though he had flatly predicted it. He was always expecting it for someone else. Ghosts need heroes.

They were really quite estranged when Fran painted Jack's portrait. She waited for him to come over and see it. I was always waiting for him to come and see my work . . .

Jack took one look and said, "I'm repelled!"

He wanted it to be all mixed up, himself almost indistinguishable from the ground and trees and stones, peering out from the brush like a jackrabbit or a skunk cabbage, or like the sixteenth of a Blackfoot Indian he always claimed to be. But the portrait denied that, because he really had become a famous hero, even to Fran. He was distinguishable. It was his own fault that he was, and there was nothing to be done about it except for Fran to paint him as a famous hero, and for Jack to do what he ultimately and very shortly thereafter did do about it.

8

Readers should cross their fingers now, and think hard about 8, or they should try not to think about 8.

We left town that summer, as usual, to go camping. Jack was already in the hospital, dying. We had been down to see him, although he didn't see us; it was clear he was dying, the doctors said so, and we knew it, but we didn't think he would really die, even though we expected it.

We spent a fine couple of weeks at Lassen, at Kings Creek, the highest camp. Then one night there came a thunderstorm, a routine event in the mountains in August, thunder and lightning and fear, and we left our stuff there to dry out and stayed in a lumberman's cabin for a few days. Then we went back. But soon after there came another storm. That was not routine. Fran had a dream that stormy night about meeting Jack on Polk street, she asking him shouldn't he be in bed at the hospital, and him saying it was OK, he was through with the hospital. The next morning she insisted on going into town and called up the hospital to find out how he was doing, and they told her he was dead.

|