|

April 1998 | Jacket 3 Contents | Homepage | Catalog | Search |

John Tranter reviews

|

|

This collection of recent poems was complete and ready to publish when John Forbes suffered a heart attack and died suddenly at his home in Melbourne on 23 January 1998. He was forty-seven. where the heart burns

He wrote about politics too. His ‘Ode to Karl Marx’ begins with a nod to Miss Havisham from Great Expectations — Old father of the horrible bride whose

Years of training in art theory lie behind poems such as ‘On Tiepolo’s Banquet of Cleopatra’ (the painting is helpfully reproduced on the cover) which opens: Any frayed waiting room copy of Who

And he wrote dozens of love poems, almost all of them ornately oblique. One in an earlier book goes into lengthy technical detail about the sounds of the various armaments audible in a television news report of the bombing of Baghdad. A love poem in this book, though - a kind of ‘still life with girl and heroin’ - comes close to the simple sentimentality he had previously abjured. |

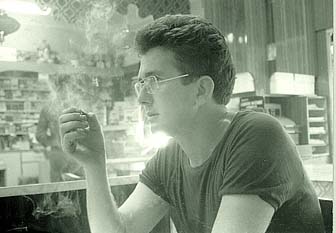

Photo: John Forbes, Newtown, Sydney, 1978, photographer unknown

|

|

For all their intellectual dexterity, his poems are easy to read, and Forbes was almost self-consciously Australian. There are a handful of poems in this book that pin down our larrikin style with grace and accuracy. Forbes grew up on the fringe of the military - his father was a civilian meteorologist attached to the Air Force - and his poem about the Anzac Day march (the last poem in the book) compares various military cultures, from the English to the Germans, from the French to the Scots. All this is just a leadup to his final point:

He was sardonically aware of the contradictions of a society that occasionally gave modest handouts to poets (he had enjoyed a small number of Literature Board grants) and lavishly rewarded greedy entrepreneurs like Christopher Skase and Alan Bond for their cunning. The sneering references to rich yuppies that pepper his writings, though, seem to me to be tinted with envy. it’s important to be major

This is the Laconic Mode, a way of talking that is peculiarly Australian, and grows from a dry refusal to acknowledge either the hurt of failure or the glow of success. Except for his art - and there’s no doubt it will impress the empty future - Forbes was more acquainted with failure than success, and the sting of various defeats (menial jobs, unrequited love, friendship gone sour) was not assuaged by the knowledge that he was mostly to blame. continually disappoint

In the poem ‘Anti-Romantic’ he concludes that self-conscious bitterness is the best response to a consideration of ‘poetry driven by love or breath’. Art or life both require this, he tells us, but in case you are inclined to be too cute about this hard-earned insight, there’s a final admonition - an ethical scruple that surely bears the imprint of his Catholic schooling: but your attitude like

Sadly, all of our large publishing houses are now controlled by foreign-born managers whose main loyalty is to the profits their overseas shareholders demand. Few of them now publish individual volumes of new Australian poetry. It’s left to small firms like Brandl & Schlesinger to carry that baton. |

link : how to order your copy of Damaged Glamour from Sydney’s Gleebooks |

|

Jacket 3 — April 1998

Contents page This material is copyright © John Tranter, the Estate of John Forbes and Jacket magazine 1998

and Jacket magazine 1998 |