|

April 1998 | Jacket 3 Contents | Homepage | Catalog | Search | Keeping Something Happening

Russell Chatham

|

|

Russell Chatham was born in San Francisco in 1939. He moved to Montana in 1972. He is a self-taught painter, print-maker and writer. Since 1958 he has had more than three hundred one-man exhibitions of his art, which has been enthusiastically collected by the rich and the famous including Peter Matthiessen, Eudora Welty, Hunter S.Thompson, Peter Fonda, Robert Redford and Jack Nicholson. He has written hundreds of articles, reviews and stories about fly fishing, bird hunting and conservation. |

|

¶ Noel King: What role do you think the small press plays in relation to the overall culture of book publishing?

Russell Chatham: My view of things, and it’s promoted by being physically distant from any publishing centres, derives from the fact that I was discouraged by experiences I had with larger publishers. As time has passed it seems they have taken less and less interest in what you might call serious books, or literary books, and look primarily toward large-profit items. And I suppose you can’t blame them: this is the world they live in and that seems to be what’s happening. That’s a discouraging situation for a lot of writers. When I started Clark City Press, it was always going to be a very small press; we could only think of publishing five to eight books a year. This was a lot for us but not much relative to the possibilities out there. And one of the things that was an eye-opener for me was how many manuscripts came unsolicited to us; hundreds, if not thousands, many of which were eminently publishable. What that showed me was how many serious writers had nowhere to turn, they were scratching at every possible opportunity to get their work published. And then you realise that the larger, traditional publishing houses aren’t picking up on these works. According to the sources I have, those companies no longer even have readers. Twenty years ago a person could say, ‘send a manuscript in to Doubleday’ and somebody would sit down and read it and if it was good, they might even consider publishing it. That doesn’t exist any more. So, particularly for younger people or people just starting out, it’s a very discouraging landscape to view. ¶

What are some of the main things that you think have changed in US book publishing and book culture?

Once you turn the reins of a publishing house over to the book-keeping department rather than the editorial department then the whole focus of the company changes. Publishing has always been a financially complicated and difficult business. However, certainly at the time I was growing up, a publishing house was run by publishers and the accountants worked for the publishers. Now it seems the other way around. I think this is symptomatic of every bit of what could come under the label of ‘culture’ in America, not just the publishing industry. It’s all money-driven. ¶ Speaking of that, you’ve been here about twenty-five years now, having initially come up from the Bay area, San Francisco to visit Tom McGuane?

That was the initial reason for the visit. At that time Tom had had some luck with his first couple of books and he’d always wanted to have a place in Montana and a place in Key West, the Florida Keys, for fishing and hunting reasons as well as living reasons. So I just came up here for a visit, to fish, but I already had a clear sense of what was happening to California and it was very discouraging: a population explosion, it’s slowed now but they’re bursting at the seams. It’s just too crowded, and I knew I needed to be some place where there was space, a less expensive life, that was an issue too. Throughout history, artists and writers have always looked for places that are both beautiful to live in and cheap to live in. And this place qualified. ¶ Why do you think that has happened, this intense focus on Montana as ‘the last good place’?

I think it’s the last of the romance in America. Everything else has been swallowed up, chewed up and spit out. In the early part of the century, when travel wasn’t so easy, you had a place like Carmel, which, though only 100 or so miles from San Francisco, seemed incredibly distant. Today people commute to work in San Francisco from Carmel. By the same token, the Golden Gate Bridge across the bay was built the year before WW2 started and Marin County was a vacation place for San Francisco people, and considered to be quite a long distance off. You had to take a boat to get there. During the war people were preoccupied with the war effort and defence and so forth, so it really wasn’t until the late 1950s and into the 1960s that people realised you could drive to Marin County in five minutes or so. |

|

|

¶ Noel King: What are your plans with the next phase of Clark City Press?

Russell Chatham: I don’t want to rehabilitate Clark City Press back into a company per se. What I discovered is that either you stay very small, with two or three people and publish just a few books a year or you get into the mid-range where you need six or seven employees and your expenses — especially if you’re bidding for books — means that it becomes very difficult to make it work economically. ¶ Your books have high production values, good paper, lovely covers...

That’s not that hard to do. You just have to want to do it. I’ve seen a couple of books recently where I thought the production standards were kept quite high: Chez Panis does very good books. This change in the publishing industry has pretty much happened over the last ten to fifteen years. Over the last seven years or so I’ve been asked by New York publishers to help design or help out with almost thirty books. They never take your advice! ¶ When you refer to this change in the dynamics of publishing you mean the shift from publisher-oriented companies to accountant-oriented companies? Yes, I don’t have a lot of contact with that world. I know the fellow who owns and operates Atlantic Monthly Press and he’s trying to do it right. And I suspect that Farrar Straus is probably still hanging in there reasonably well, and someone reported to me that Charles Scribner III is still hanging on by his fingernails. But the other big houses have just gotten bigger. ¶ What other small presses do you admire?

When I first got into this business I found out who the other small publishers were by going to the American Booksellers Association. At that time, and I suppose this is still true, Graywolf was doing a good job and certainly had an interesting list. ¶ Steerforth Press in Vermont seems to fit this pattern.

Well, that’s where you’re going to see these good quality, interesting books. There will always be a certain number of serious writers whose work can translate into what we would call a best-seller, someone like Amy Tan, whose work hits a chord in the public consciousness and something happens. But the interesting and ultimately discouraging thing is that what constitutes a literary best-seller is pretty small numbers. And I didn’t know those numbers when I started out. |

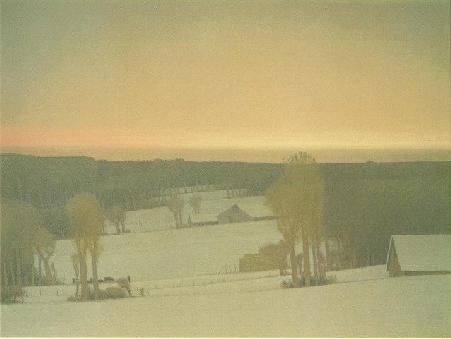

View of Winter Light, an original lithograph by Russell Chatham; |

|

¶ Noel King: What effect do you think the chains have on publishing in the States?

Russell Chatham: There’s no question that the power of the chains disadvantages the very people who used to be the backbone of the book business, the small, independent bookseller. Now, what they call ‘book supermarket’ people — whether it’s Dalton, Barnes and Noble, Doubleday — buy a few copies of every book that’s available and create a book supermarket with thousands of books, and they hire someone at minimum wage to stand by the cash register. That’s not bookselling. ¶ The book-malling of America... Exactly, and if they choose to do so they can really make the tail wag the dog big time. Let’s say a store like Dalton or Barnes and Noble makes a deal with a publisher. Let’s say the publisher comes into a meeting — someone like Dell or Doubleday, someone with a great deal of resources behind them — and they say we’d like to print 500,000 copies of this novel by X, and we’ll do that if you’ll promise to put 10 copies in every one of your stores, on the front table or in the window. So it’s all a deal, it’s nothing to do with whether the book is good or bad, or anything else, it’s a deal, and that’s not helping. ¶ Has Clark City Press ever applied to any Foundations for assistance with its productions?

It’s never occurred to me to do that; I always figure I can spend that time thinking up some way to earn the money. But some presses do. Graywolf, for example, converted their operations to non-profit status, which enables them to become eligible for various grants that are not available to businesses. There are some very wealthy Foundations but it becomes a particular talent or trick to know how to write the requests for grants. There’s an art museum in Billings and all they do all day is write grant applications to try to get money; they have people on staff who only do that, who specialise in that. ¶ How did you come to publish a couple of books by Barry Gifford? He’s a very interesting writer and he submitted a manuscript to Jaimie Poltenberg (Jim Harrison’s daughter) who was in charge of production. It gave us another dimension, another voice that was quite different, and each book was appropriate to a small press. Both Jamie and I liked the work, so we did a couple of things with him. ¶ How did your list come together in the first place? It was quite organic. It started out with some things of my own that I wanted to get back in print, and I knew of some poetry of Jim Harrison and Dan Gerber that deserved to be in print but wasn’t. ¶ How did you come to reprint a book like Kathryn Marshall’s My Sister Gone?

Because Kathryn Marshall lived here! That’s a very tough book but it’s a good book and it should never have gone out of print. And that was my attitude. If you found something that had some foundation to it but had gotten lost between the cracks you should try to bring it back. |

|

Noel King teaches at Macquarie University, Sydney. |

|

Jacket 3 — April 1998

Contents page This material is copyright © Noel King, Russell Chatham

and Jacket magazine 1998 |