|

This is JACKET 1 — December 2001 | # 1 Contents

| Homepage |

|

Roy Fisherin conversation with John Tranter |

|

The English poet Roy Fisher was interviewed at his home in a remote village in Derbyshire, high in the Peak District of England on 29 March 1989. The interview was recorded for radio. It has been edited slightly to make it easier to read. |

|

[ Roy Fisher reads his poem ‘Stopped Frames and Set-Pieces’ ] John Tranter ... Roy, would you like to talk about how you came to write that poem?

Roy Fisher: It’s a composition from pictures. Every one of those items was an item from a collection of photographs. I think every one was in fact either a news photograph, or taken out of an illustrated magazine, taken out of context. The important thing for me was to ignore the structured context in which the thing had originally had a meaning, and let it hang about. In many cases it hung about for years. The photograph of the Indian statue I still keep on my wall, because it’s pretty. I probably owned it for ten or twelve years before I decided to sit down and write it. John TranterWhat about the form that it has on the page? It isn’t written out in rhymed verse, or even in lines of verse at all, it’s written out to look like ordinary English prose. Roy Fisher: Yes, it’s meant to be meticulous English prose. It’s a collage, the main thing for me was the juxtaposition, the movement from one sort of thing to another, following my nose. I’d have a literally statuesque passage followed by a bit of frozen newsreel, which was the scene about the shooting in the street, and then I’d want another set piece. And that’s the title I gave to it. |

Photo of Roy Fisher |

|

I was very interested in the way in which a movie is made of frames. This is a work which I wrote in, I suppose, the mid sixties, from a picture collection I was making four or five years earlier. So in fact it comes from an interest in cinema. You know the way in which you have an unbroken rhythmic series of images in conventional cinema, and once you start ‘freezing’ an image, you get a different sort of energy. A different thing is being described. The one about the dog is the central one. If you have a thing that is obviously a dog in motion, in a movie sequence, the dog would carry on moving. If you just look at the stopped frame, you literally don’t know what you’re seeing — you’re seeing a splat like an inkblot picture, a scatter picture, then you reconstitute it, and it’s a story again. Let’s look at the matter of poetic development. Where did you begin as a writer when you first decided you wanted to write poetry rather than prose, or make movies or whatever else you might have wanted to do? And where did you learn to write from? Did you learn to write from English models, or from models in other languages?

I started at the age of nineteen, from the first place I could find anything which I thought crudely exciting enough to break the rather grey surface of my mind. I knew there was something that I wanted to make. I didn’t know what it was. All I’d studied up to that stage, and had felt any sympathy with was a sort of statuesque nineteenth century diction. Matthew Arnold was my idea of sensible development from the heady stuff like Keats. Had I started writing in that mood, all would have been lost, I think. But I knew better than that, and was completely stuck, and literally had — it may be a very common experience — a feeling of something wanting to be made, but not telling me at all what it was. I got in through reading surrealist or neo-surrealist texts, things like Salvador Dali’s autobiography, or Dylan Thomas’ prose works. I think Eliot said that poets learn to write by being other writers for a while, and then moving onto another one.

I was being all of them, at that period. Then I went on, I got more of a smell of what the hard stuff was like. Oddly enough, from Robert Graves, who was surfacing, again, about this time. He was having one of his periods of being interesting. This was the early fifties, The White Goddess had come out and that interested me very much. Too much, at the time. I was interested in the really very tough but committedly imaginative strain that there is in Graves. What about the influence of the English ‘Movement’ poets of the fifties, did you ever feel drawn to want to write in that style at all? No, I couldn’t even mimic it. I can do imitations of things but I couldn’t understand enough of what made those people tick, even to send them up. What about Larkin? Larkin was one of them but his writing style is very impressive, even to a young writer, I’d think. Even if you don’t like it, you have to respond to it.

Yes, I had a sort of near brush with Larkin. Larkin was about eight years older than I am. It was the point where I started having some currency, the things I’ve been talking about happened when I was a student around the early 1950s. I then stopped, and purely by this sort of chance that happens to people who are just sitting in their bed sitting rooms wondering what to do in their nights off, I wrote one or two little pieces without any content to them, without any meaning. They were little decorative fantasy pieces, and I sent one off to local radio station. It got broadcast. Then I had a thing in a magazine called The Window, which was a not very establishment-minded little magazine, John Sankey ran it. |

|

|

One of the people he chose to be in this issue of Corman’s magazine, along with me, was Larkin, who seemed to him not typical of the English and also obviously very good. I think at that stage the full biliousness of Larkin’s outlook on life hadn’t come through in the verse, and Larkin was not a man who was making pronouncements about the century having moved on too fast. He hadn’t cultivated his Eeyore qualities, the persona he developed in middle life. [’Eeyore’ is the donkey in a series of stories for children by A.A.Milne, author of Winnie-the-Pooh. ] Larkin was sent a complimentary copy of the magazine, to see what kind of magazine he was going to be in. He opened it and — I don’t know whether it was the impact of what he read, or the fact that his book was coming out shortly — he sent by registered post a countermand to withdraw all his material. So he wasn’t published along with Irving Layton and Charles Olson and Larry Eigner and untidy people like that. But our paths were close together for a little while there. That must have been an interesting moment in English literary history. If only one could have realised what the past and the future would have looked like in fifty years time ...

Well, if he’d been in the magazine, I don’t think that sort of thing would have stuck with him. He wasn’t interested in opening the experience out. So you read the American writers but at a bit of a distance, and it was a distance you wanted to keep. Was that was because of where you were born?

I’m a Midlander, which is a very particular sort of race. It’s supposed to be nowhere at all. I haven’t got the near-nationalism which Basil Bunting has. He had himself referred to as a ‘Northumbrian’, because Northumbria was an old kingdom, and its language is descended slightly differently [to other kinds of English] and its political institutions and its exposure to invaders from Scandanavia, and the way it was treated by the Norman French invaders, all this gave it a different fate from the body of England. I’m a Mercian, if Bunting was a Northumbrian. I come from the no-account bit in the middle. It also helps to determine where you appear in print, doesn’t it?

It can do. One mustn’t caricature, and certainly the people I think of as being on Establishment railway lines will fight back indignantly if you imply that certain ways are open to certain people and closed to others. But I think it certainly happened in my generation that ... it’s quite easy to be invisible. I don’t mind being invisible if it gives me independence. But there were times when you could feel more invisible than you wanted to be, simply because of the very strongly metropolitan habits that England has. Some of them are aware of it. I was reading a recent autobiographical piece by Thom Gunn. He said he left England and went to America partly because of how easy it was, he saw, for him and his friends to get into print in London. He went to Cambridge, and he said he went down to London, and he found it very easy to get reviewed well by his friends. For him I don’t think there was any point in any of that at all, because it didn’t have anything to do with what you were worth as a writer.

He’s a good guy from that point of view. The carry on of that quick burst into celebrity that Thom Gunn had, it lasted him for twenty, twenty-five years in this country. He’d come back for a reading — I met him at a reading full of parties of school kids, and he was surprised. He says no one pays this much attention to him in the United States, what’s it all about? It was the momentum. I remember picking up the London Magazine in my early twenties, and saying ‘Who’s this new poet? He’s got a come-on. He’s got a style.’ And there he was, bam bam. Ted Hughes the same. It’s not to be sneezed at. Yes, and it has to do with how well you can reach an audience too, doesn’t it? If you find it hard to get into print, and hard to get publishers who can distribute your books well, then you tend not to have as much of an audience as you might have. That’s true. You mentioned in an earlier conversation that there was a period when you felt unable to write, then you broke out of that.

I was a late starter. In my early and middle twenties I wrote in a very solitary fashion. It was very much to do with fantasy. I was pretty mad — in a quiet kind of way, but my head was filled with a very thick and lurid soup. And I wrote this thick and lurid soup. I wrote virtuoso pieces with metaphors dripping and trailing all over the place. Then almost by accident, in the middle of writing a lot of very decorative work, I found that I was making contact for the first time with people with a demanding aesthetic — and these were people like Creeley and Corman — whatever their aesthetic was, it was at least demanding. I met people like that for the first time, saw them at work. Oh dear.

So I was on the rocks. I was on the rocks for years. I couldn’t write at all. In the middle of this period I met Stuart Montgomery who was setting up Fulcrum Press with a very interesting list, almost entirely of Americans neglected in America — when you say that these were people with names like Louis Zukofsky, Robert Duncan, and Gary Snyder, you realise you’re talking about a very strange period in American literature. These were books like New Directions books which were temporarily out of print, or things which British publishers had taken an option on and not taken up — it was the late sixties and people were going to read poetry. So he built up a list of people like that. Were they with a mainstream press?

I suppose the mainstream press, as England regards itself, has always been Faber. Fulcrum was not in a sense an experimental or avant garde press. It knew very well what it thought was quality. And it knew very well what it thought was going to be part of the literary history of the times. So it could reach out for Americans at full stretch, or in full flight, as [Robert] Duncan was at that time, and say ‘This we can endorse. This we can use.’ What’s you relationship with academia? You went into academia fairly early in the piece, yet you seem to me to be the sort of poet who hasn’t gone into the academic line at all. You seem to have veered away from it all through your writing life. I suppose so. I’ve never been conscious of there being an academic literary tradition around me in the country. I couldn’t in this country say that so-and-so is a ‘campus poet’, in the way in which you can say this about American poets who live on campus. I think it’s a very American thing, isn’t it? Yes. If you can graduate in Creative Writing, and take a doctorate in it, and then get a job teaching it, that’s a quite different life from anything that’s available over here. There are scraps of it. There are one or two programs; very few programs for a credit, and they are minor parts of degree courses. There was a time when you could be a writer-in-residence on an Arts Council grant at a university campus, but that by English standards was regarded as far too leisurely an existence. You just officially seemed to be staying in a place of comfort. If you had that sort of job you weren’t required to run credit programs. You would be seeing the odd people who wrote a bit and you’d do a reading and get some of your friends in to do a program of readings. Funds for that sort of a thing in this country nowadays tend to be attached to all sorts of community activity programs and they’re out of academia almost completely, I think. So what’s the work you’ve done in universities?

I was just an ordinary literature teacher. I worked in colleges for along time. We have — or we had — an sort of intermediate higher education institution, which was essentially for training teachers. And in those days they were of a more modest grade than universities. People didn’t need to be so well qualified to get in. I quite enjoyed working at a couple of those. I was teaching teaching for quite a lot of the time. I was teaching ‘method’ rather than teaching ‘literature’, and in fact I ducked out from teaching literature straight, as much as I could. I taught all sorts of things, like story-telling skills, and children’s literature, and how to control a class, and things of this sort, having been a school-teacher for a time. |

|

|

|

When I went to teach in a university in the end, I carefully joined an American studies department and taught in a American studies program, so as to teach literature which was of interest [to me]. I just taught modern literature, nineteenth and twentieth century literature, fiction and poetry. I did that really so as not to get caught up in the rather head-cracking debates about how to teach English literature as such. You know, you get into the debates about how much theory there should be, how much structuralism there should be, how much Marxism there should be. Those are truly academic debates. I wasn’t too bothered with them. They’re political debates too, debates about who has the power and who doesn’t, and who controls the latest fashion and who doesn’t. They all seem to me to be reductive. In the long run they turn out to be dedicated to honing the curriculum down and down and down to a smaller and smaller canon which will have certain sharp socio-political edges. I’m not interested in that. I talked to Frank Kermode a bit about that when he was in Australia recently. He went through a very rough time at Cambridge going through exactly that kind of argument. He would indeed. Trying to loosen things up a bit, I think, and introduce new ideas, and of course that’s hard to do in an older university. Old is old, too. That goes back hundreds and hundreds of years. You have a weight of tradition to push against there which can be quite frustrating. And all those debates to do with academic fashion, they’re conducted with what is apparently a very high moral purpose, but they’re very introverted debates, and to my way of thinking they come down to matters of intellectual style rather than of cultural substance, or anything which has got an active muscle in it. The [New York] art critic Peter Schjeldahl argued a few years ago in Australia [in his keynote address to the Adelaide Festival Artists’ Week in February 1986] that fashion and style are very good things because they help to focus the spotlight of attention on what’s the newest and the best and the most energetic work being done in any particular field, and they save you the impossible task of having to read literally everything, which no one can do. Oh yes ... I take that ... ah, I would probably have taken it more when I was younger. The way I get to feel as I grow older and see a few more cycles go around — and I’m fairly slow at catching fashions and knowing what’s going on, and people never tell me anything — probably I’m the sort of person who manages not to be told things — but as I see the cycles go around, I get a bit spaced out. I sit back and ... try to think on eternity, and what is substantial and what is historically important over a long period. I don’t tend to get very much disturbed or very much excited by what seems to be going on this minute. I don’t get too much from it. You’ve just had three books out in the last three years from Oxford University Press, which seems like a blast of fashionability.

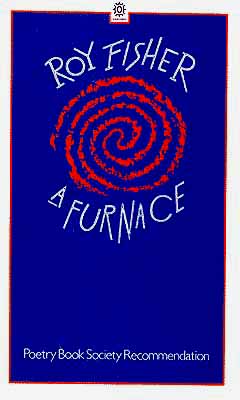

You get remarks on some books that say ‘This book is made from recycled paper.’ My books maybe ought to have a warning saying ‘This book is made from recycled books.’ In fact the Oxford Collected of 1980 was almost entirely composed of most of four Fulcrum books, plus one Carcanet book. Then A Furnace, which was a separate book, and is a single free-standing work, was almost all I’ve published during the eighties. And the Poems 1955–1987 is a recycling of the 1980 Collected, with ten or twenty pages added. So some of the contents of these books are having their third and fourth and fifth time around. That’s what writers used to do a hundred years ago, isn’t it? They’d bring out a book, then the next edition would have a few more poems, and they’d go on adding to the one book. Each book they brought out was a more complete version of their work. So that as their lives went along, the book grew with them, as it were.

Well, yes. That’s quite congenial to me. It’s probably why I publish with Oxford, who have done a few books of that sort. I don’t write much, you see. Also a lot of what I do write is an attempt to make sense, or make art, or make form of what were inchoate experiences some while ago. Or even inchoate writings which I want to rewrite or revisit. I am not a verse diarist. I don’t think of myself changing enormously with circumstance. I don’t write very autobiographically in terms of things that happen to me or what I go and do. I chew away at the relationship of my head to the world as I try to understand it, and there’s a lot of internalisation going on. And the art changes, the way I want to use artistic methods change. You don’t rewrite history, in the way that Auden is supposed to have done. In his own texts? Not a lot, not a lot. Quite a lot of the things I have done within recent years have been lookings-back at myself by way of the texts that I wrote then. And I’ve seen myself through the way I wrote, and wanted to go back and understand that self better through understanding what those texts are twenty years later. But I don’t see my work as a kind of thing like a politician’s diary, which I think may be what Auden was thinking of. I don’t think I’ve got that sort of personality. One thing that’s very important in your work, it seems to me, is the influence of place on what you write. It seems you often recreate a place in your work, particularly Birmingham, where you grew up. Now you live out of Birmingham, in the country. I can’t imagine two more opposite environments — Birmingham, busy and industrial, completely different to where you live now, which is very quiet, farming country way up in the hills in the middle of England where a car might go by every five minutes.

It’s very different. But oddly enough, I don’t seem to be able to go to any bit of country without finding traces of mining and industry and people’s lives in it. When I was living in Birmingham which I did for forty years, I suppose I was stuck with it like a child out of Wordsworth. For some reason I never really swam in the city as an urban person, although I lived in and around the town a great deal, and was in the pubs and in the jazz clubs and in the educational system of the same place for decades on end. |

Photo copyright © John Tranter 1997 |

|

And I suppose the other relation is this, that —what I was trying to say a few minutes ago — that having been brought up in the city — rather as if exiled in it, but exiled from what, I was never told! — I thought of the city as something to question. As I say, I wasn’t a real town kid who just withered if shown a cow, you know, the typical town intellectual who says ‘Yes, yes, very nice, take me back, take me back before the pubs open.’ I wasn’t one of those town people, and I just saw it — partly because of a somewhat oblique or withdrawn personality — I just saw it as an agnostic, I had to say ‘What is it? What’s this great blob? What’s this noise, what is all this red brick? Why are people like this?’ So you’re not a recluse. You’re just a person who likes to get away from it all the time, if you can. I’m a gregarious hermit. Talking about jazz reminds me to ask you — do you get your rhythms from the jazz keyboard? If I played the piano with the rhythms I write with, I’d get shot. Because the rhythms of my writing are I suppose of the family of the rhythms of ... Samuel Beckett, or somebody like that. It comes from very close to silence. The linguistic rhythms I use sit, almost like philosophical discourse, very close to silence. And I’m not very interested in any kind of go-go rhythm. The music I play is very much mainstream jazz. It’s got to have some snap ... and ... I just like swing. I probably play the piano much more emotionally than I write. This allows the writing to be as cold as anything if I want it to be. I don’t need that thrill from writing. I don’t even need my writing to be particularly juicy, because if I play, it’s juicy and snappy or it’s nothing, you know ... or it’s sentimental. If I play ballads, or ‘Sophisticated Lady’, or ‘Body and Soul’, I make quite a meal of them. But I never want to write that kind of poetry. So I’ve probably split myself quite happily two ways, in those two arts. I play the piano in quite a juvenile, enthusiastic fashion. Jazz piano is an American art, too, isn’t it?

Oh, yeah. Somebody once asked me in an interview years ago who influenced my writing and I said without thinking about it, Pee-Wee Russell, you know, the Chicago clarinet player. And I wasn’t being smart. Because I learned that music, I learned it as outsider music, as music that you had to go around corners to find. Music that was made against bourgeois traditions and academic traditions. I was studying the jazz of the twenties and the thirties. And that appealed to me very much, and I could understand the way of thinking of people who didn’t want to play the same thing twice ever, and who had for me — and I still admire it very much in musicians — a mixture of good old-fashioned, not too worldly-wise sense of Romantic creativity. You know, tonight may be the night, this number may be the number when I astonish myself, I may hit it this time. A combination of that with an honest artisan approach ... yes, I know how to begin and end a number, I know how to play in time, I know how to get my fingers on the right notes, without any ‘faff’ about personality and fame. There’s an interesting contradiction there, isn’t there? There’s nothing more personal than an individual jazz style. That’s what makes you who you are as a jazz player. And yet you can’t say anything about yourself when you play a jazz piano. You hit keys that make notes and that’s it. You can’t say ‘I was born here, and I grew up, and I had an unhappy love affair, and I failed an exam, and then I got a university medal ...’ You can’t say anything about who you are or where you come from ... you can’t express anything about who you are, at all. Well, it’s abstract. Yes. But I don’t overtly, so far as I know, do many of those things in the writing. I think a lot of the poets that you and I are going to be interested in don’t do that all that much. That’s marginal. Though we’re interested in the gossip. And if we give readings, or there are little notes about the authors in the back of the book, people grab on those, because not many of the poets that I’m interested in as craftsmen and practitioners of a tradition, not many of them are the ones who make a meal of their mistakes, or how much booze they can take, or how many women they can pull, or how they stand among their peers. The personal plight poetry isn’t so much in it ... There’s that rather delightful essay by Frank O’Hara called ‘Personism: A Manifesto’ where he talks about avoiding all of that stuff about displaying your emotions.

Yes; that figures. But I can jump immediately from Frank O’Hara to Brecht ... the appeal for me of Brecht is the fact that although you can read him one way and say that this man lived through the cataclysms, and he slid between the jaws of the monsters that were grinding on him, and he lived this way and he lived that way, but you know perfectly well that the work is based methodologically — I’m talking about poetry — the work is based on ways of getting moral judgment free from autobiography, and that autobiography is there from the point of view merely of necessary witness. It’s interesting with O’Hara that almost all of his work deals with his own actual experiences from day to day, so it’s extremely personal in that sense. And yet he never uses poetry to puff that up into anything important. It’s just there as material. He knew the difference between what poetry was, and [what it] was not. So he’s good.

I’ll read a few excerpts from the long poem I wrote four years ago, which is called A Furnace. It’s built very much on the lines of other modern long poems — it’s a collage of various sorts of experience, some of them what I can only call cultural, some of them autobiographical, some of them are a working over of what I think now about things I’ve written before. |

Cover of The Dow Low Drop — New and Selected Poems, Bloodaxe Books, cover painting ‘The Autumn of Central Paris (after Walter Benjamin)’ by R.B.Kitaj (1972–73) |

|

I was brought up in the shadow of these things, huge black iron constructions turning to half-mile stretches of rust, great monstrosities, things belching smoke and so on and so forth. These were my environment, and I’m very interested in where they came from, and where they’ve now gone, because they’re disappearing as soon as I look at them. You can go to steel towns or coal mining areas and see them razed flat and turned into other things. You can see the good old human race at work making itself comfortable, making itself rich, blotting out what it’s doing. That interests me.

[ Roy Fisher reads from A Furnace, Oxford University Press, 1986, page 12 to page 19, part of Section II, ‘The Return’.]

This was a poem where I knew that I’d somehow got to convey I suppose two things, one of which is fairly easy for me after a few decades of practice, which is to say what I’ve seen, to notate, to report. Because I suppose you get used to describing in terms that people can say ‘Yes, I see that. You can draw.’ The other thing which is very difficult for me is to somehow enact what I can only call my cast of mind, you know, the angle that the world hits me at, and what it does to me. I take it that this is the most difficult thing that anybody has to do, and maybe some poets can learn to do it quickly and deftly, by how they describe, and I suppose I’m fairly used to being able to get a cast of mind by moving through a bit of material quickly, what you might call an acute state of the cast of your mind. If we’re thinking of Frank O’Hara, you pick a little thing like ‘Lana Turner Has Collapsed’ or ‘The Day Lady Died’, where so much comes through in a little diagonal passage of that man’s mind, through a newspaper event or through a public event. |

Photo of Roy Fisher |

|

If you read it once, and you read it again, they’ll start to chime together. And the systems in the poem ... for instance, there’s a system to do with identities which is a word that pops up in that sequence a few times, but at one point it’s been laid down, and it’s chimed on, as if it were an orchestral work, certain instrument sounds, certain bell sounds, and anybody who is patient enough, and is going to give his life up [laughs] to moving through this poem a few times is at least going to be helped by the formal recurrences of a certain bit of vocabulary, or certain icons, you know, like the old woman in black sitting by the wall, there’ll be several old women in the poem, there’s a system. It was written to be read off the page, wasn’t it? It’s written to be pored over. I also wanted to write it as something which I could read with pleasure myself, as a sound sequence. I didn’t want it to be a cut-up, I didn’t want it to be a bag of bits. I did want it to have a certain amount of forward progression, in the sense of the episodes beating along through it. At least that was what I was after. How has the poem been responded to by people who’ve read it or reviewed it?

Not badly. I don’t think I’ve encountered reviews which say, oh what the hell, this is a self-indulgent piece of pomposity. What’s happened is that the quick reviews tended to say ‘This work is a bit more humane than we’re used to with Fisher. There are actually some people in it, there’s actually a bit of emotion, a bit of political snarling, indignation, anger even. There is supposed to be. It’s certainly there in me. Whether it’s in the poem ... is not for me to say, but people immediately seem to get a feeling that just possibly, by going on at greater length than I often do, a certain amount of blood and emotion builds up and is secreted. |

|

|

Now what happened was that I just felt a wish to catch a certain sort of discourse, a certain sort of tone, which was controlled, but at the same time as wacky as I wanted it to be. I suppose one way of looking at it came from the observation — I don’t know if I made it as long ago as this — but it’s about the way I would write poetry and the way I would write dreams.

[ Roy Fisher reads some excerpts from The Ship’s Orchestra. I see some history in your writing, and also some regionalism. And I guess this is compared to New York writers or London writers or writers from Melbourne Australia. I was wondering how you see the work you do as part of a tradition that might touch on the work of Geoffrey Hill’s Mercian Hymns on one side and Bunting’s Briggflatts on the other.

Geoffrey Hill comes from a place really very near to where I come from. He was born around Bromsgrove which I suppose is twenty miles, thirty miles at the most, from where I come from. He comes from a rather similar social class. Obviously enough, he’s got a rather different stake in matters from mine. He’s — I think — always more structured and more controlled. What about [Basil Bunting’s long poem] Briggflatts? It appears to me to have some connections with what you were doing with Birmingham, in a way. You’re not alike at all, but ... Mmmm. Compared to, say, Peter Porter, or ...

Oh yeah ... We would be different sorts of Roman poet, wouldn’t we? I suppose Bunting and Porter and I would be listening to classical poetry in different ways, and they will know much more about it than I do, having the languages and all. But I suppose where I would come at all into the same area as Basil Bunting is in that particular thing I’ve tried to express, the difficulty of showing your cast of mind in an extended form of — how did I put it? — trying to illustrate what it’s like to be in your head for a day or a week. I don’t think this is a very important point, but I should mention it. It seems to me from the perspective of Australia that your work is more ‘American’ than ‘English’ English. Have you run into that problem in England as an English poet? That people have said ‘Well he’s not really English at all, he’s more American than English, therefore we don’t like him, or we don’t understand what he’s trying to do.’

I’ve been puzzled over. You know there are various little labels that get put on you, and these get parrotted from year to year without being updated. There’s one which still gets said, which is that Roy Fisher is far better known in America than he is in Britain. I rather wish that this were so, but it hasn’t been true since about 1960 when I was slightly known in America and not known at all in Britain. What about the writer J.G.Ballard? I’ve read only a few stories by J.G.Ballard. It seems to me that he’s contemporaneous with you, and in some of the things that he does with contemporary English prose, he seems to be doing things rather like what you’re doing. Yes. He’s free. I tend to want to feel quite internationalist about this, in that I suppose so far as I’m conscious of latching on to methods I’ve seen used in any literatures in particular, on the whole the methods I want to use, I’ve not seen used with determination, or professionalism if you like, much, in England. |

|

1. Aleksandr Blok Russian poet, (1880–1921), Blok was the leader of Russian symbolism, a counterpart of the European literary movement strongly influenced by the Eastern Orthodox faith. |

We had all sorts of experimenters popping up and popping down; on the whole I tend to think of them as ‘gentleman amateurs’, or short-fuse people, who’ll make a sudden streak, and do one thing, but don’t have too much theoretical sense. |

|

And, yes, I suppose the American label does come from the fact that in my own language — I’m no linguist, I can cope with French, and know what happens in German; apart from that I’m in translation — if I want my Russians I have to have them in translation, the Germans too, really; Italians — but yes, the general openness to Modernism, and an attitude to literature which treats it as a matter of composition in the way that painters are used to thinking, musicians are used to thinking — the English language access to that has obviously been more in American writers than in native English writers. |

Some of the books cited ....

Roy Fisher — Poems 1955–1980, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1980.

A Furnace, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1986.

The Cut Pages, Oasis Shearsman, London, 1986 [first published by Fulcrum in 1976]

The Dow Low Drop — New and Selected Poems, Bloodaxe Books, Newcastle Upon Tyne, 1996.

|

|

J A C K E T # 1

Contents page This material is copyright © Roy fisher and John Tranter

and Jacket magazine 2001 |