|

This is Jacket 1, October 1997 | # 1 Contents | Homepage | Catalog | |

John Tranter reviewsPhotocopies, by John BergerBloomsbury, 180 pp, hardback This review is 1,800 words or about 5 printed pages long |

|

IT’S SIMPLIFYING THINGS to call John Berger a Eurocentric left-wing analyst of art and culture, but I’m going to do it. He was born in London in 1926, and has written more than twenty books — mainly novels, performance scripts and art criticism. The recent novel To the Wedding was popular, and he is respected for his perceptive, unconventional collections of essays on art and photography — About Looking, and Ways of Seeing. He has lived for many years now in a French mountain village. |

|

There are narratives, that is, stories told by Berger, or told to him and retold to us. Sometimes they are reflections on a place — a ferry trip in the Mediterranean, say — or a climate — Barcelona suffocating under summer heat. The author often features in these scenes as an observer, standing quietly to one side. |

|

|

The first edition of this book was shorter, published in German, and was titled (in German) A Man and Woman, Under a Plum Tree. With a slight but politically interesting alteration, that’s the title of the first essay in the book and of the photograph it’s based on, a blurry shot of Berger and a woman standing in a small clearing surrounded by foliage: ’A Woman and Man Standing by a Plum Tree’. |

Photo copyright © John Tranter 1997 |

|

Berger has thought deeply about these things. I was impressed by his analysis of photography in the book About Looking, published in 1980. ’The camera relieves us of the burden of memory,’ he wrote. ’It surveys us like God, and it surveys for us. Yet no other god has been so cynical, for the camera records in order to forget.’ |

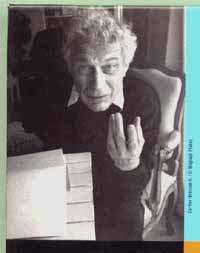

Photograph of John Berger by Henri Cartier-Bresson copyright © Magnum Photos, courtesy Bloomsbury publishers |

|

Politics. Few of the pieces are overtly political, though one — towards the end of the book — warmly presents the point of view of the Zapatista peasant rebels in present-day Mexico struggling against what Berger calls the forces of the Free Market, and another essay laments what the Free Market has done to Russia. |

|

Jacket 1 Contents page |